More than a health crisis: Covid-19 impacts are far-reaching and long-term

The Covid-19 pandemic is already causing wider consequences for societies, national economies and global relations, and these will continue for years to come. Three experts share insights on how we can better respond to the pandemic while we continue the search for vaccines and treatments.

Juliet Bedford from Anthrologica, Erik Berglof from the London School of Economics and Devi Sridhar from the University of Edinburgh Medical School look at the wider and longer-term impacts of Covid-19.

From the local to the national to the global, they highlight why communities need to be at the heart of the response, why vaccine nationalism is not a good strategy long-term, and how crucial international cooperation is to changing the course of the pandemic

1. What are the indirect health effects of Covid-19?

Devi: What we've seen with outbreaks in the past – whether it’s Zika or Ebola or other endemic diseases like malaria – is you have all these knock-on effects on the health system that perhaps you don't notice when you're just responding.

Outbreaks are like black holes, they draw in all resources, all expertise. We go backwards on agendas like child survival, or dealing with different disease campaigns, or even providing basic primary healthcare services. This includes delayed vaccination – if schedules for measles and mumps are delayed, for example, how many people might die of those?

It's a really tricky one, because if you don't address Covid-19, everything is going to get destroyed – it's like a tidal wave. But as you try to fight it all these other agendas are being neglected.

2. Who is most affected by the pandemic?

Devi: If Covid-19 has shown anything, it’s that wealth is the best shielding strategy. Wealthy individuals can work from home, they can set up their lives so they avoid getting the virus. The people who can’t are the people who are relying on their daily wage, people who live in slums, people who live in crowded housing.

We've already seen it in the UK – one of the risk factors is coming from a deprived area. The argument for me, around who should get vaccines and treatments first, is who is most likely to be exposed to the virus and who is least likely to be able to protect themselves. I think that will map onto areas of deprivation across the world.

Juliet: Although there are some similarities in terms of how this pandemic is playing out across the world, we have to be very aware that who Covid-19 is affecting most and how they are being affected vary hugely across different countries and different population groups with different vulnerabilities. Some of this is to do with the existing societal structures, some with the response mechanisms that have been put in place, and some with the much broader socio-economic issues that the pandemic is having an impact on.

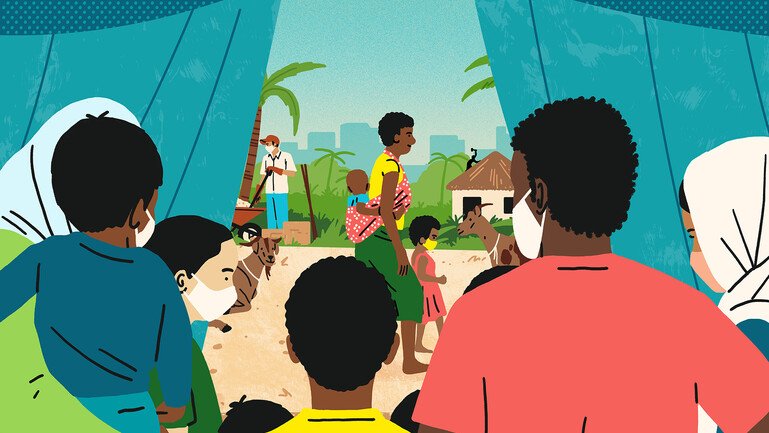

For example, if you think about informal settlements in Africa, some of the world’s largest informal settlements, they face huge challenges around implementing a policy like physical distancing. Space is very limited, and so is access to services, water and sanitation. This creates vulnerabilities and a lot of heightened risk for populations that are already under huge stress and don’t have social safety nets as we do in other countries.

And similarly, if you look at forcibly displaced populations, some of the highly vulnerable populations in East Africa, for example, the pandemic is layered on top of other very complex challenges – the movement of people, and their experiences in what are already very overcrowded and under-resourced refugee camps.

How do we better tailor response interventions to those local contexts? What will the impact on those populations be? The short-, medium- and long-term effects are going to be quite different and far-reaching.

Erik: Developing and emerging countries are particularly vulnerable and particularly affected by the pandemic – even if they respond very firmly to the crisis, it’s very hard for them to sustain those measures over time. That’s because they have weak defences: health systems are often poor, governments have fewer resources to intervene, and individuals don’t have savings and depend on daily sources of income – so it’s very difficult for them to socially distance.

The economy of a country plays a huge role in its ability to sustain various measures – both pharmaceutical interventions, such as pursuing the development of vaccines and better treatments, and non-pharmaceutical ones, such as lockdowns.

Until we get the virus defeated everywhere, the world economy will not return to normal.

3. How is the pandemic impacting national economies?

Erik: First of all, there are direct impacts from people and governments responding to the virus. People stay at home because they are cautious, and governments encourage them to stay at home to reduce contagion. So you have lower output in the economy as much work cannot be performed from home, but you also get lower demand because people are not buying as much and are postponing investment decisions.

The indirect impact is the combined effects of all those reactions by individuals and governments that affect global demand. We've seen it initially in commodities, particularly oil. And we also see it in terms of a massive reassessment of risks and, at least initially, people taking back money that they have invested in emerging and developing countries. Another badly hit area is tourism, which many of the developing countries are heavily dependent on. That's something that will be affected for a long time by the pandemic. And another thing to mention is remittances – people living outside their own country, transferring money back to relatives and friends in their home countries, many in Africa and Central Asia. This often contributes 20–30% of the total income in that country. Lower commodity prices, a fall in tourism revenues, a drop in remittances and withdrawal of capital are often interrelated.

Overall, the indirect impact has actually been much worse for many countries. The global effect is stronger on advanced and middle-income economies – as they’re typically more engaged in the world economy. But developing countries are ultimately more affected because they have weak defences to begin with and tend to depend more on a few sectors, like commodities and tourism, and rely more on remittances.

4. Why should countries act collectively and not selfishly?

Devi: Infectious disease outbreaks show how we’re all tied into this together – we’re all in the same boat. For Covid-19, we've had such a competition between countries about who is doing better and who is doing worse, instead of thinking actually, we're all going to do worse if a few countries do worse, and we will all do better if a few places do better.

If every country looks after itself, it's a recipe for disaster. To deal with Covid-19 you need to have countries working together on a coherent strategy – is it to drive the infection to a low level? Is it to accept a certain level of infection? Then countries need to work collectively on response strategies: instead of everyone fighting over the testing reagents, how do we work together to get the reagents?

I think every country wants the same thing – to protect people’s lives and livelihoods – so it's just how do we bring leaders together to realise it's in our collective interest to work together.

Erik: There are two arguments for why countries should act collectively: a values-based argument and one that I would call the ‘enlightened self-interest'.

If we believe that suffering should be reduced globally, we need to think about how we can reduce the impact of the pandemic in developing and emerging economies.

But even if we didn’t care about their wellbeing, there are important reasons for why we shouldn’t try to address this pandemic alone. If we are relying only on our own resources, then when it comes to threats that don’t respect borders, we are going to be much less equipped to defend ourselves.

For example, when it comes to the production and distribution of a vaccine, we need to think as a collective and make sure that it reaches everybody, because that is in our own self-interest. As long as the virus is active anywhere, it’s a threat to all of us.

5. Who are the key players who can change the course of this pandemic?

Erik: There are a number of institutions that we need to back up much more firmly than we have so far: the WHO (World Health Organization), the World Bank, the IMF (International Monetary Fund), the regional development banks. They are absolutely critical for how we can change the course of the pandemic.

All these institutions have responded reasonably well, but they are running out of firepower, and the global community has a tremendous responsibility now to make sure that the initial response is carried on. We need to look at various ways to support them – either by providing more capital, ensuring some of their operations or just making them more effective. That support must come from institutions like G20 and regional collaborations like the European Union and the African Union.

And we also need to think about how we restore confidence and trust in the World Trade Organization (WTO). There have been many examples of protectionist measures by individual governments to make sure that their populations would get access to protective equipment or to specific drugs. These have been flagrant violations of the spirit and the principles of the WTO in terms of trying to redirect specific deliveries of equipment. You can even see this within countries, between states in the US, there’s been a crazy bidding war and lack of coordination. The rest of the world is very much like that, or even more like that. We need stronger enforcement of the rules of the game that the WTO represents.

Juliet: Communities are the first responders. We are all responding in different ways and at different levels to this pandemic – from an individual, personal level to a household level to the community level, and for many people professionally as well as personally. Everybody is involved. This is one feature of the pandemic that sets it apart: for many people, particularly in high-income countries, this is the first time they have ever been faced with this kind of threat, and it is frightening. It is a threat to their health but also their lifestyle. We shouldn’t underestimate the level of anxiety this creates.

Key players at the local level are important, influential individuals and civil society groups, and local networks of influence and representation. There is also the general population who take on roles as carers, roles as first responders, and getting involved in local task forces.

This pandemic has shown that we need to better adopt the attitude of ‘one for all and all for one’. It is individual actions which together are going to make for a better response, a response that is going to help overcome transmission much more quickly. We need to be working collectively. And this is a challenging thing to do in the 21st century with so many isolationist tendencies. We need to be bringing people together, because only when we are working effectively collectively do we know that individually we’re going to be safe.

6. What can we learn from past epidemics?

Devi: If you’d asked about how to improve global health security pre-Covid-19, I think many of us would have focused on poor countries, places with low capacities. But Covid-19 went backwards and hit the rich world first.

So one thing is rethinking our idea of global health security – that it's not like the rich world will be completely fine and the poor will suffer. Many poorer countries have done remarkably well so far, ahead of European countries and the United States. We all have something to learn from each other, instead of just instructing poorer countries on what they should be doing better in crisis.

Second is prevention. Overreacting to an outbreak is better than waiting around and seeing how things play out. I think if countries had all reacted preemptively in January and February, we wouldn't be in the current situation. Many places stepped back and said, we'll see what happens, and we still see that constantly. Public health for me is all about preventing something, responding quickly and then taking the heat later when people say you overreacted because the crisis never developed.

Juliet: Societies where disease outbreaks are very common know how to deal with them and how to take community-led approaches. Several high-income countries have not sufficiently implemented key lessons learnt from disease outbreaks in other parts of the world, in terms of basic shoe-leather epidemiology, how to do contract tracing (particularly with vulnerable and difficult-to-reach populations), how to communicate with affected and at-risk communities, how to strengthen trust in response structures and mitigate mis- and dis-information.

How do you convey health-related and behavioural information that is rapidly changing? You need trust, and trust is not something that we can just snap our fingers and create; it has to be built over time. To my mind, it can only be done when we have a much more effective two-way flow of information: pushing out information from the response about signs and symptoms, how to protect yourself and prevent transmission, what to do if you need care etc; but also learning from communities over the short, medium and long term, and being able to tailor our actions to make sure that interventions are as contextually relevant and as appropriate as possible.

If you have a central government or local authority pushing out messages that people can’t actually follow or comply with – for example wash your hands and improve hygiene, if that’s not possible because you have limited access to water and sanitation facilities – then those people are being further disempowered. We know from previous outbreaks that people are resilient and show incredible initiative – nobody wants to get sick – but we must find ways to ensure that individuals and local communities have the information and resources they need to act.

We have to change our approach to better recognise that individual and collective actions are very much at the centre of any response, and to make sure that people have the agency to be able to respond appropriately and to take responsibility for themselves and, by extension, their communities.

7. What should guide policy makers and global leaders when making decisions about Covid-19?

Juliet: No epidemic is ever just a health issue in isolation, and Covid-19 has emphasised this on the global stage. There are huge economic ripples and societal repercussions being felt across the world because of this virus. We need to be looking at it in terms of an economic issue, a livelihood issue, a social issue and a political issue too. So trying to find the balance between those interrelated but often conflicting areas is very difficult.

For example, at what point do you prioritise education and balance the risk of children going back to school with the fact that they need an ongoing education and the additional support structures that schools provide? At what point do you balance having people gathering for funerals against the risk of transmission when actually it’s hugely important – emotionally, psychologically and socially – that people can collectively mourn and honour a loved one’s life in the way they feel most appropriate?

These kinds of issues which are both personal and local have been magnified onto the global stage. And it’s those kinds of issues that global leaders are having to struggle with – balancing risk and potential risk with needing to put in place mechanisms to make sure that, going forward, people are safe in their day-to-day life and that the day-to-day structures of society can flow again, including education, healthcare, economics, the movement of people, domestically and internationally, the movement of commodities etc.

Devi: It’s an impossible situation because you can't just let the virus go, because health services will collapse. On the flipside, lockdowns have enormous costs and you can't just lock down society for ever either.

You can't have it all with this virus – schools open, free moving over borders, job security, people out in pubs, weddings going ahead. The places that have done better have recognised the trade-off, and the places that are suffering are trying to do everything.

So you have to make strategic choices and the countries that I think have done well realised that early on. We’ve seen New Zealand, Vietnam and Taiwan saying, we're going to prioritise daily life but restrict freedom of movement. And South Korea saying, we'll have some freedom of movement, but we're going to do mass testing and tracing, and that requires giving up privacy.

I think of all the things to lose, the thing that will affect the largest number of people the least would be international movement, because we have to get kids back at school, we have to get people into jobs and you just try to support tourism through either forming bubbles or through supporting domestic tourism. It’s these difficult political decisions that leaders are having to weigh up and balance on a daily basis.

Erik: Policy makers are much better off if they intervene early. There have been many warnings about the consequences of a pandemic. Some countries took them seriously and were better prepared – both physically, having better supplies of critical equipment, drugs, masks and personal protective equipment, and intellectually – thinking through the response. Also, it seems that countries that had recent experience of epidemics or people in the government who really understood how epidemics work, such as Taiwan and Vietnam, have been more successful.

Policy makers are facing the same choices at the global level – how should we use our limited resources over time? There’s a strong argument for front-loading both measures on the medical side, to address the health emergency, but also on the economic side, to make sure that people can stay at home, and their businesses can survive. These things are closely related.

We’re funding research to better understand what causes and drives infectious diseases to escalate and the solutions to control their impact.

There are currently no open funding opportunities for Infectious Disease. Learn more about the funding we provide.

8. What is the best-case scenario?

Devi: A best-case scenario is a highly effective vaccine, which is safe, cheap, has limited side-effects and doesn't need to be kept cold while being stored and transported. If a large enough number of people are vaccinated, then we could reach a point where the virus is circulating at very low levels, where’s it’s unlikely we would have resurgences.

But even with a vaccine, we’re not going to eradicate Covid-19 anytime soon across the whole planet. If we have a vaccine and a treatment together, and a rapid test as well, then we’ll be in a really strong position. It would be tremendous if we could get to that, and that’s the optimism I have.

Erik: There’s a tendency to rely on science – that we should get a vaccine and then it’s all over. Or that we can develop antivirals and ways of treating patients better. All those things are important, but we cannot rely on them alone. We need to think much more widely and broadly about the challenges – we need the social sciences to help design interventions and protect those most vulnerable.

A good scenario is, of course, if we get a vaccine. Having said that, in the past we’ve also seen that, when we get vaccines, the interest of countries that benefit from vaccines in solving the issues that particular illnesses or epidemics are causing elsewhere goes down. So we need to make sure that even if we manage to immunise populations in the rich world, vaccines also come to low- and middle-income countries and conflict zones.

Even if we don’t have vaccines, in a positive scenario we will have collaboration through international organisations. For me, the most important thing now is that organisations like G20, the EU and other regional organisations take a stronger role. That’s the most promising scenario. If we are relying solely on individual countries to work on their own, it’ll be unlikely to get to a solution very fast or get to a good place.

Juliet: The best-case scenario is that we quickly learn from the failures and weaknesses that Covid-19 has highlighted so acutely, and make significant improvements in terms of how prepared we are and how we respond to a global pandemic most effectively. Should a new pathogen emerge that was similar to SARS-CoV-2 but that was more virulent and had a higher case fatality ratio, the world would still be woefully unequipped to deal with it. A higher level of true global cooperation is absolutely essential and urgently needed.

Secondly, in some settings, physical distancing has made communities come together to be more resilient, has made individuals be dependent on others in constructive ways, and has made sections of society open up to certain vulnerabilities. Moving forwards, we don’t have to go back to life as it was. There is going to be a ‘new normal’, but we have a window of opportunity to make that new normal better and more inclusive – not just for ourselves, but for others as well.

That is the most optimistic scenario that I can envisage: whatever the new normal looks like, it is a more equitable new normal.

The future of Covid-19

This article draws on a paper exploring four possible futures of the Covid-19 pandemic over the next five years, and the global impacts of each trajectory.