Tracking the health effects of climate change around the world

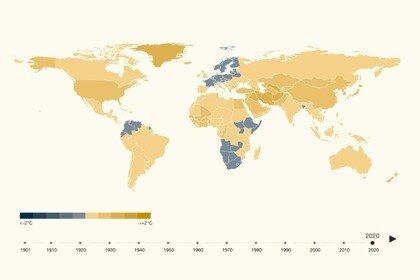

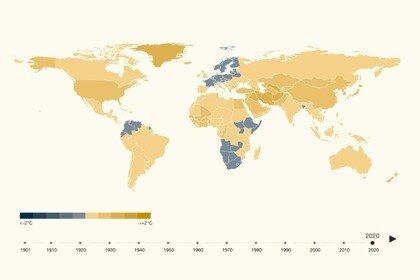

Data is a powerful tool for understanding the health effects of climate change. Click here to explore 120 years of global climate data.

Climate change is a global health crisis, and that includes mental health. Find out how it’s impacting our mental health and what can be done to prevent and manage it.

David Hogsholt/Panos Pictures

Melanie Primor (31) holds her nephew Christian Jay Jocoy (1 month) in the classroom that her family shares with four other families in the Camaya-an High School in Loboc, Bohol, Philippines.

Primor's district (purok) was ordered by police to evacuate their homes due to typhoon Rai.

The high school served as evacuation centre and then relocation centre for the families of the barangay of Valladolid who lost their houses. Valldolid saw an estimated 6-8m surge flood caused by typhoon Rai which demolished most of the houses there in 2021.

Research Manager, Evidence (2022–2023), Wellcome

Research Manager, Evidence (2022–2023), Wellcome

Content warning: this article mentions suicide.

The 2023 Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) stated that there is very high confidence that rising global temperatures will lead to an increase in mental health hazards. With mental health problems holding back millions of people every day, it’s crucial we understand how climate change might affect our mental health.

Climate change is leading to more frequent and extreme weather events such as floods and storms. People living through these can be exposed to potentially traumatic events such as witnessing serious injury or death. As a result, many people will experience higher levels of psychological distress and a minority may develop more serious mental health problems, such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression, or substance use disorders.

Extreme weather events can also have impacts on some of the social and economic determinants of mental health by leading to unemployment, homelessness, or food and water insecurity. This can, in turn, also detrimentally affect mental health.

Individuals, families, and communities often display high levels of resilience in the face of extreme weather events. According to a 2010 study, most people fully recover or maintain good mental health with appropriate psychosocial support,. However, with escalating and more frequent extreme weather events, we do not know if this sort of resilience can last in the long term.

Data is a powerful tool for understanding the health effects of climate change. Click here to explore 120 years of global climate data.

Climate change is causing temperatures around the world to rise, which can have a variety of detrimental impacts on mental health. For example, hospitalisations for psychiatric disorders and emergency psychiatric visits tend to increase during heatwaves. Rates of suicides have also been shown to be higher during heatwaves and are expected to increase with rising temperatures, although evidence on the link between heat and suicide remains mixed.

We do not yet have a good understanding of what links heat to poor mental health. One hypothesis is that higher temperatures can worsen mood, leading people to feel more irritable and stressed and worsen symptoms of mental health problems. Globally, heatwave periods have been shown to be linked to more negative sentiment expressed online.

Heat can also disrupt sleep, and poor sleep can worsen mental health problems. One very large study that analysed ten billion sleep observations found that warming nights are eroding human sleep globally and unequally, with this effect being three times larger for residents of lower-income countries.

Finally, certain medications for mental health problems can disrupt the body’s ability to regulate temperature, meaning that people taking these medications are particularly vulnerable in high temperatures.

Climate change and increasing temperatures have been shown to increase levels of allergens and pollutants present in the air, leading to worsened air quality.

Emerging evidence suggests that poor air quality can negatively impact mental health, in particular depression and anxiety. One large study among all people aged over 65 years enrolled in Medicare in the US showed that short-term exposure to pollutants (PM2.5 and NO2) was associated with higher risk of acute hospital admission for psychiatric disorders.

Similarly, higher levels of air pollution have been linked with increased mental health service use among people living with psychotic or mood disorders in the UK.

Exposure to air pollution during childhood and adolescence has also been shown to be associated with the development of mental health problems as young people transition into adulthood. It's suggested that this is due to air pollution impairing the normal development of the central nervous system.

Climate change is a major factor in the emergence of infectious diseases in new parts of the world, such as malaria, dengue, and zika. The survival, reproduction, abundance and distribution of pathogens, vectors and hosts can be influenced by the changes associated with global heating.

A failure to slow global warming is providing many deadly diseases with the opportunity to expand their reach, putting the health of millions of people at risk. Read on to understand how climate change and infectious disease are linked, and what we can do to limit the damage.

Physical and mental health are intrinsically intertwined. Being exposed to higher rates of infectious diseases can have significant detrimental impacts on mental health due to being hospitalised or living with the long-term consequences of severe infection. People living with certain conditions, such as neglected tropical diseases, can also face stigma and discrimination.

As well as direct exposure to climate hazards, a growing number of people report psychological reactions related to confronting the prospect of climate change.

There is not a clinical diagnosis for these experiences, but there have been several attempts to capture them with new terms. These include (among others):

solastalgia – the inability of finding solace in a familiar landscape due to environmental degradation

ecological grief – the sense of loss emerging from experiencing environmental degradation

climate anxiety – a feeling of anxiety in the face of climate change

One large study of 10,000 children and young people in 10 countries found that 45% of respondents said their feelings about climate change negatively impacted their daily functioning. Another study found that negative, climate-related emotions were associated with more symptoms of insomnia and poor mental health.

Some argue that these represent adaptive and constructive psychological reactions to climate change, and that we should not pathologise them. There is emerging evidence that higher levels of climate anxiety can be, in some cases, linked to higher levels of pro-environmental behaviours.

Although climate change is a global phenomenon, its impacts are felt unequally across the world. The same is true for the effects of climate change on mental health, with communities and groups of people that are less able to adapt to climate change more likely to experience the brunt of its mental health consequences.

While most research on climate change and mental health has been conducted in Europe, North America, and Australia, many of the places that are most vulnerable to climate change are in low- and middle-income settings. These communities are often most at risk to climate change exposures such as droughts and with less resources to adapt to them. There is not a huge amount of evidence from these communities, but one small 2019 study conducted among Ethiopian pastoralists found that water insecurity contributed to extreme worry and fatigue.

Another small study in Tuvalu, a small island developing state in the Pacific Ocean highly vulnerable to climate change, found that a high proportion of respondents experienced psychological distress in relation to climate change stressors to a degree that caused impairment in one or more areas of daily life.

Indigenous communities can be particularly connected and dependent on the natural environment surrounding them, putting them at a higher risk of experiencing poor mental health due to climate change. These communities also possess important forms of local knowledge and expertise that can contribute to their resilience and inform climate change responses in other areas of the world.

Land Body Ecologies (LBE) is a global transdisciplinary network exploring solastalgia, a concept that sheds light on mental distress specifically caused by environmental change. They bring together land-dependent and indigenous communities at the forefront of today's environmental crisis and land rights issues, and connect collaborators in a range of fields – from human rights, medicine or psychology to arts, design, sociology and ecology – across a network located in Finland, India, Kenya, Thailand, Uganda and the UK.

LBE are the fourth residents of The Hub, at the Wellcome Collection.

Other groups considered to be particularly at risk of experiencing poor mental health due to climate change include:

people experiencing homelessness

people living with severe mental and physical health problems

To avoid the worst impacts of climate change on health we must transition away from our dependence on fossil fuels towards clean, renewable energy, stop deforestation and restore our natural habitats.

Different forms of climate change mitigation strategies can have multiple co-benefits with mental health. Shifting to more active modes of transport where possible, such as cycling or walking, can have positive impacts on mental health given the link between physical activity and mental health.

Similarly, increasing access to green spaces can also have positive mental health impacts. Wellcome-funded research has shown that being in a green space such as a forest or a park, even if just for 15 minutes, can immediately and momentarily improve mood and reduce feelings of anxiety for young people.

Even if we reduce emissions and meet global targets of zero emissions by 2050, many of the impacts of global warming are now irreversible. So, to protect the health of populations into the future it is essential that we also adapt to ongoing climate change.

Multiple effective evidence-based interventions for different mental health disorders exist. Some have been tested in settings that may be particularly relevant to climate change, such as disasters or with migrant and refugee populations. However, more research is needed on how to intervene as early as possible to promote mental health and prevent and manage mental health problems in the context of climate change.

Wellcome’s climate and health work envisions a world where catastrophic climate breakdown is averted in a way that allows human health to flourish. This includes a future in which no one is held back by mental health problems in the context of climate change.

This article was first published 7 November 2022.

Stay up to date with some of the biggest stories in global health, and how we're advocating to improve health for everyone.