A Gambian midwife’s perspective on extreme heat and pregnancy

Extreme heat will only get worse with climate change, and it has been linked to health risks for pregnant women and their babies. We spoke to a midwife and a researcher in The Gambia to learn about their perspectives on the health impacts of heat on pregnancy.

Louis Leeson/LSHTM

About a year ago, a woman was brought into a Medical Research Council (MRC) clinic in The Gambia, unable to speak, sweating and with signs of dehydration.

“Initially we were all thinking of a lot of things. Is she epileptic? Did something bite her, did something hit her? We couldn't come to a conclusion,” said Edrisa Sinjanka, the midwife and nurse who attended to her.

When Sinjanka questioned her, he learned she had been working out on the field under the hot sun. She was breastfeeding and hadn’t been menstruating. It turned out she was pregnant again.

“There are three factors combined here: nursing mother, antenatal mother and also heat,” Sinjanka said. “Probably, if she was not pregnant, she [would not have been excessively] sweating.”

This encounter was one of the times Sinjanka realised the impact of heat on pregnant women was becoming a problem in The Gambia, the smallest country on mainland Africa, where inland temperatures can reach as high as 45°C.

Extreme heatwaves are already happening and are projected to affect around 14 percent of the Earth’s population as the world warms by 1.5°C.

Studies have found extreme heat to be linked to adverse pregnancy outcomes globally such as:

- stillbirth

- low birth weight

- fast weight gain in babies

- preterm birth

The latest Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) Sixth Assessment Report published in March 2022 noted pregnant women and mothers as particularly vulnerable to heat, with spontaneous abortion also among the health risks.

The Gambia is one of the most vulnerable countries to climate change and its many health impacts despite contributing little to its underlying causes. How does extreme heat impact pregnancy?

A midwife’s perspective

Sinjanka, 55, became a licenced midwife in 1998 and practiced midwifery or nursing since then. From 2019 onwards, he has been a midwife at MRC The Gambia field station in Keneba, a rural village where subsistence farming is common. The village is about three hours from the capital Banjul on the coast.

As a midwife, Sinjanka is in a frontline position to witness how heat affects pregnant women. He often sees women, particularly those doing farming work for hours under the sun, come to the clinic with complaints of mild pains and dizziness, sweating and dry mouths or lips.

He acknowledged the difficulty in making direct links between heat and adverse pregnancy outcomes, as heat illness symptoms, such as nausea, vomiting or weakness can be due to a variety of conditions.

“At times you will also see some miscarriages,” he said. “You wouldn't know exactly what has happened or what is going on, you will not have any concrete evidence to tell you that this is the reason why this particular woman has had a miscarriage.”

But context matters. He’s only able to draw the connection with heat and offer advice after considering the nuance of women’s situations and experiences, which includes the inevitable nature of their daily work and the impacts that might have.

“Obviously, if you ask somebody to stop work where they earn their living, at times it's difficult,” he said.

“Some will heed your advice and try to reduce their working hours in the field but some will tell you, ‘my grannies have been doing this, in fact they've been working more than I do but nothing happens to them so nothing will happen to me as well.’”

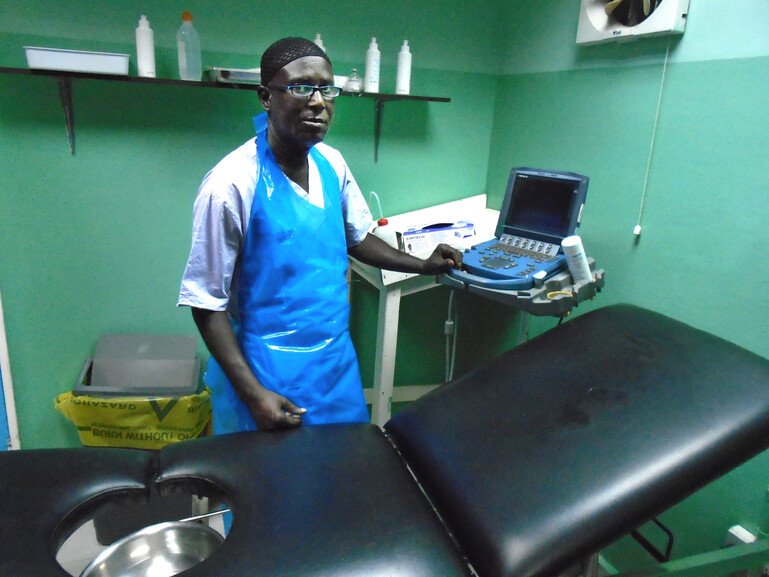

Edrisa Sinjanka is a midwife in Keneba, a rural village in The Gambia. As a midwife, Sinjanka is in a frontline position to witness how heat affects pregnant women.

Edrisa Sinjanka

The disproportionate impact on women

The impacts of climate change disproportionately affect women’s health – beyond just pregnancy – and heat is no exception. While there is plenty of research linking heat to adverse pregnancy outcomes, there’s not much on why that is.

Clinical Research Fellow Dr. Ana Bonell moved to The Gambia in 2019 to carry out Wellcome-funded research aiming to answer this question through detailed physiological studies of mothers and their foetuses. The study included interviews with pregnant women working as subsistent farmers in West Kiang, The Gambia.

Bonell learned that cultural factors contributed to gendered dynamics around exposure to heat. Women in The Gambia will work on rice fields and gardens to grow vegetables during the dry season with no mechanisation. This requires manual labour to constantly pull water for crops due to the lack of rain.

While women grow food for their families, men focus on cash crops to sell. It’s an added burden for women as primary carers of children as they ensure food supply and stability for the household.

“Women generally are much less able to pick up and move. They have dependents that they are caring for, both elderly relatives and young children. So they are then more likely to stay in a place even if that place is feeling the impacts of climate change,” Bonell said, citing other climate change impacts that can affect women such as food security and water scarcity.

“When you look at policy setting, women just aren't really at the table. So their issues and their concerns are not really brought forward and not being acted on.”

From Sinjanka’s day-to-day perspective at the Kenaba clinic, the most vulnerable mothers are ones that have no choice but to spend hours exposed to the sun.

“You rarely see antenatal mothers who are working in the offices come here with heat problems,” he shared. “Most of the time the ones you see are the ones working in the hot sun or coming from the field.”

Bonell did not directly attribute heat exposure to any specific pregnancy outcome in her research. But she looked at changes in maternal temperature, blood pressure, heart rate and whether there was immediate impact on the baby at that time to inform the research.

“What we found was, while they [pregnant farmers] were out in the sun or in a heat-stressed environment, that this led to heat strain in the mother and we saw an impact on the foetus, in that we saw a direct relationship between environmental heat stress and foetal heart rate going up,” Bonell explained.

“On our more detailed scan we tried to look at how well the placenta functions under heat stress. We found this relationship that hasn't previously been documented showing that as heat exposure increases, you get a reduction in the placenta's ability to deliver nutrients and oxygen – a vital supply to the baby.”

In another Wellcome-funded study published in December 2022, Bonell found that for pregnant women working in extremely hot temperatures, there was a 17% increase in strain on a foetus for every extra degree Celsius in extreme heat stress.

Education is the first step

Despite The Gambia demonstrating a strong commitment to tackling climate change, there’s still a lack of awareness among women and midwives about the causes of climate change – let alone the risks of heat on pregnancy.

“At times when you talk to somebody about heat, they'll just look at you [and say] ‘people have been living in heat for decades so what are you talking about?’” Sinjanka said.

Bonell’s research has helped raise awareness about the risks, with women being very receptive and becoming more attuned to what they were already experiencing with the impacts of heat.

This awareness has allowed both midwives and women to adapt in whatever small ways they can, from reducing hours in the sun where possible to self-cooling methods such as drinking cold water.

“With anything I guess the first step would be education. Education for the midwives but also education for their patients around risks of heat,” said Bonell.

This is why Wellcome is funding more research to understand what can make mothers and children vulnerable to extreme heat. Of the various aspects of climate change that have an impact on maternal health, heat is particularly in need of more research. Studies around it can ultimately help inform real-world action for adaptation.

Bonell’s research is one significant step in the right direction. We need many more steps to protect our future, and the most vulnerable populations.

“Buying a bag of rice is not easy for a lot of families, so obviously you need to go to the field to work to earn a living,” Sinjanka said. “Things are changing. But as we speak some people are still struggling, and they are still going to the farm.”

We’re funding vital research into the impact climate change has on human health around the world, at national, regional and global levels. Explore our current funding call:

Advancing climate mitigation solutions with health co-benefits in low- and middle-income countries

This article was updated on 6 February 2023.