Are we ready for extreme heat? A climate expert explains

One billion people across the world face the risk of heat stress if Earth warms up by 2°C. Professor Jean Palutikof tells us about her research into interventions that could help.

What’s the motivation behind your study on managing heat stress?

When I saw Wellcome’s Climate Change and Health Award, I worked in climate change adaptation with my colleague, Fahim Tonmoy, who is from Bangladesh.

At the time, there had been several papers written by physical scientists about the challenge for countries in South Asia from the combination of hotter temperatures and a very humid climate, which increases the risk of heat stress.

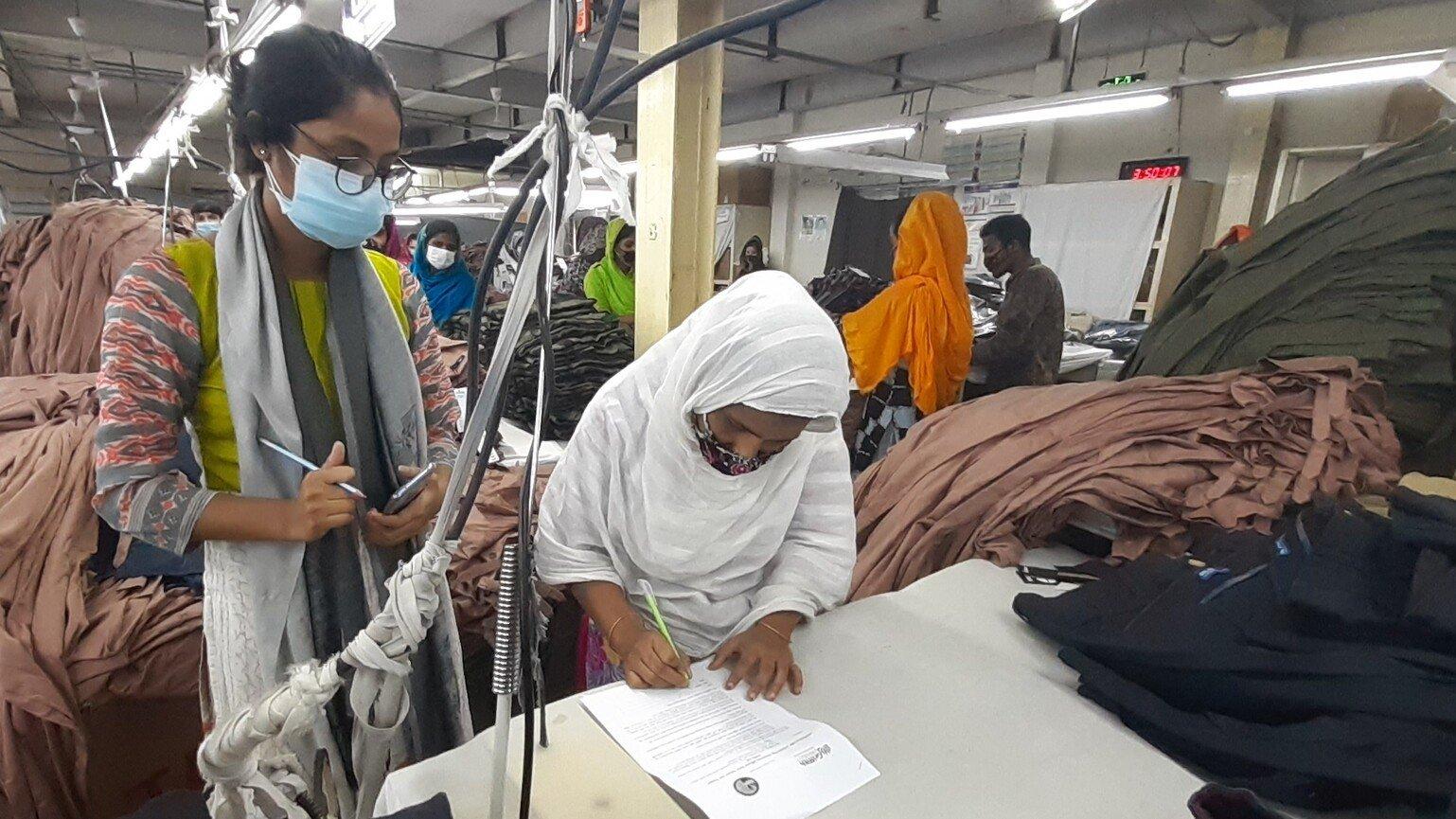

We were working in Australia, but we knew about the heat challenges in Bangladesh's ready-made garment (RMG) industry. The RMG industry is very important in terms of social development in Bangladesh and around 60% of the workforce is female. It supports women of modest education and provides them with a living wage, giving them considerable autonomy within their community.

The papers we read dealt more with outdoor workers and we thought, what is climate change going to mean for people who are already working in excessively hot indoor conditions? Is the industry going to increasingly rely on air conditioning and become an increasing source of greenhouse gases?

We’re now in the project’s third year and we’re analysing our findings.

How does heat stress affect the human body?

We interviewed 67 workers in one factory in Dhaka, Bangladesh, to find out what the climate inside the factory is like and how people find the working conditions.

They experience conditions that I would find completely impossible to do any work in. In the summer, temperatures can reach over 40°C on the uppermost factory floor where the ironing and packing activities are concentrated. Some workers will say they are perfectly comfortable in those conditions – they're very well acclimatised. But many of them say that they’re too hot and humid.

In terms of what heat stress means to them, they can feel physically uncomfortable. They can develop headaches, feel faint and their skin can become clammy. Their cognitive processes can also be affected, which from a health and safety perspective, when you’re dealing with sewing machines and irons, is not a great position to be in.

How has the Covid-19 pandemic impacted your research?

We've had some difficulties because of Covid-19. Originally, we had planned to travel to Bangladesh to support our project partner the Bangladesh University of Engineering and Technology to do the worker surveys and instrument the factories, but that's not happened. Instead of being able to travel, we’ve had to find local groups to work within Bangladesh. This has turned out to be a positive experience. We’ve made new contacts, reduced our greenhouse gas emissions, and the surveys and instrumentation have been done to a high standard.

Our project partner the University of Sydney has a climate chamber. It’s essentially a big room where they can control and measure the climate inside it. So, they’re able to reproduce the climate of the factory according to what we have measured.

Three or four study participants, mainly students, sit in the chamber and iron or sew away. We heavily monitor them to understand what is happening physiologically to their body under various conditions. Of course, the participants are not acclimatised in the same way that our factory workers are, so it’s not an exact reproduction.

Research volunteers simulating ready-made garment factory worker tasks in a climate chamber at the Thermal Ergonomics Laboratory, University of Sydney.

What interventions for managing heat stress have you tested so far?

We’ve built a computer model of the factory in Bangladesh and we’re testing interventions inside that environment.

We’ve looked at green roofs, using plants like short grass to cover the factory roof, and white roofs, which are a highly reflective coating to reduce heat. These reduce temperatures by around 2-3°C, so they’re reasonably effective but we’d like to do better.

We’re now looking at how shading the roof and walls affects temperatures and our partners at the University of Sydney are looking at personal interventions. That includes the effects of changing hydration levels, the amount of clothing worn and personal workstation fans.

But thinking about climate change in the longer term, the interventions will have to be primarily about building design if we’re going to reduce the internal temperature of the factory.

What do you hope to do next with your findings?

We want to test these interventions to see how well they work in the factories as opposed to the computer models.

There have been dreadful accidents in RMG factories, like fires and building collapses. The customers in western countries who buy the clothes that these factories make are aware of the problems and keen that working conditions are improved.

The factory owner we surveyed in Dhaka owns four factories in the city, and he’s willing for us to test these interventions and demonstrate to his customers that he’s trying to improve working conditions for his workforce.

Global temperatures are rising. How ready do you think the world is to mitigate the effects of heat stress?

When you look at the global picture for action around climate change, it’s a depressing prospect. There has been some progress, but certainly not enough.

When I was working at the Meteorological Office in the UK on the production of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) Fourth Assessment Report, I met government representatives who are responsible for charting policy around climate change mitigation. It’s very sad how little we achieve.

So much effort goes into global negotiations around climate change and because a few governments are unwilling to move forward on this, little progress can be made. The individual governments who make progress have to be very careful that it’s not affecting their overall economic position because some governments are not doing anything.

What are some of the actions governments and societies can take to reduce the impact of heat stress?

If you want to talk about the big picture, which is lowering your greenhouse gas emissions to reduce global warming, then you’re looking at things like energy efficiency, for example by insulating our houses better, and moving to renewable energy. We can adjust the design of everybody’s house and workplace to be cool without relying entirely on air conditioning, which releases lots of greenhouse gases.

There’s a lot that can be done in terms of adaptation to heat – whether we will do them in good time remains to be seen.

Local-scale adaptation – where you co-produce knowledge and co-implement practical strategies between scientists, researchers and practitioners – needs long term funding. It needs to be monitored and evaluated. If governments are not prepared to keep putting up the money, building adaptive strength is very hard.

What do we know now about how climate changes health that we didn’t know ten years ago?

Ten years ago, climate and health was much more around disaster management. We were already having difficulty managing the health impacts of extremes like cyclones and floods. How would we manage if those became worse or more common under climate change?

Since then, we’ve become much more aware that there are gradual risks, particularly from increasing temperatures associated with climate change. We’re also beginning to think about the risk of infectious diseases and how they will spread under climate change.

I think it’s fantastic Wellcome is taking on climate as a health challenge because there’s a huge need. Sometimes you just need more money to move things forward.

The heat is on: how are workers coping?

Farzana Yeasmin, a PhD researcher from Bangladesh, surveyed factory workers as part of the study. Here, she shares what she learned.

“I grew up in Dhaka, where the hot and humid summers usually last from March to June. Nowadays, it extends up to August. The temperature all over Bangladesh is very hot and it’s very difficult to work without any cooling device.

As a researcher on the ground surveying RMG workers, I was surprised to see their tolerance to working in high temperatures. They have a number of strategies they use to try to combat their heat stress, like washing their hands and faces, adjusting their clothing layers and showering with cold water on their lunch breaks. One worker mentioned that washing her face with cold water relieved her for a short period. Still, during high temperatures in the summer, she cannot do it frequently because it impacts productivity at work.

Climate change is the biggest threat of the 21st century. It’s projected that it will increase morbidity and mortality around the world – the evidence shows that heat impacts health. It’s a global challenge, but there are still gaps in the research.”

Professor Jean Palutikof’s career in climate change spans 48 years. She has worked at the University of Nairobi in Kenya, the University of East Anglia in the UK and at the UK Met Office, where she managed the production of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) Fourth Assessment Report.

Jean became Director of the National Climate Change Adaptation Research Facility at Griffith University in Queensland, Australia in 2008. She stepped down from the role in 2020 to focus on her research on the impact of heat stress on people working in ready-made garment factories in Bangladesh.

Farzana Yeasmin is a researcher from Dhaka, Bangladesh, studying for a PhD at Griffith University. Her study focuses on the association between heat and acute kidney injury and the effectiveness of heat mitigation interventions.

We’re funding vital research into the impact climate change has on human health around the world, at national, regional and global levels. Explore our current funding call:

Advancing climate mitigation solutions with health co-benefits in low- and middle-income countries