Summary

Diet, food systems and climate change

- Our current food systems are responsible for more than one-third of global greenhouse gas emissions.

- In turn, climate change impacts our food systems and health – from making it harder to produce food to reducing the nutrients in what we eat.

- The world needs to take action to create sustainable food production processes, eat healthier and invest in fair, science-based solutions.

How is climate change impacting the world’s food systems?

Food systems are the activities that take food from farms to mouths. That includes how we produce, process, transport, market and consume food.

Our current food systems produce more than one-third of global greenhouse gas emissions – the main driver of climate change.

More than half of the food systems’ greenhouse gas emissions originate from the demand for meat and dairy among high consumers of these foods. It’s also a result of modern industrial agriculture, which is highly dependent on fossil fuels.

Greenhouse gases affect plant and animal growth and cause rising sea levels, warmer oceans and extreme weather and climate events.

In turn, climate change is impacting our food systems and our health. How?

Climate change is making it harder to produce food

Rising land and sea temperatures, droughts, floods and unpredictable rainfall is harming livestock and crops.

For example, countries in southern Africa have been experiencing drought since late 2023, leading to a decline in maize production, a staple crop, and threatening food security. Meanwhile, floods in the UK following Storm Babet in 2023 submerged entire fields under water, ruining crops.

Globally, one in five deaths are attributable to poor diets caused by low consumption of healthy foods such as whole grains, fruits and vegetables. Climate change will reduce the yields of these foods and put more people's health at risk.

Climate change is reducing the nutrients in what we eat

The sixth assessment report from the UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) highlighted that rising CO2 levels in the atmosphere will reduce the nutritional quality of our food. That includes proteins, iron, zinc, and some vitamins in grains, fruits and vegetables. Without these critical nutrients, more people will be at risk of micronutrient deficiencies, leading to serious physical and mental health consequences.

A systematic review of evidence found that reducing our vegetable intake could increase the risk of noncommunicable diseases, such as coronary heart disease and stroke and different types of cancers. Moreover, not eating enough vegetables and legumes could also lead to nutrient deficiencies.

Climate change is contributing to food shortages and higher food prices

Inequities in the food system are inextricably linked to poor diet and health. Around 3.1 billion people could not afford a healthy diet in 2021. And more than a quarter of the world's population faced food insecurity in 2022.

Climate change will further exacerbate this issue. With food shortages, food prices will increase, putting more people at risk of food and nutrition insecurity, chronic hunger and loss of livelihoods. Diet-related conditions such as obesity, heart attack, stroke and diabetes will also rise.

These are just a few of the existing and future impacts.

What can be done to protect our planet and our health?

To protect people’s health and create a healthier planet, we need to act now to adapt to and mitigate climate change.

Here are three strategies that could help:

1. Change the world’s eating habits

Eating healthier can help fight the climate crisis.

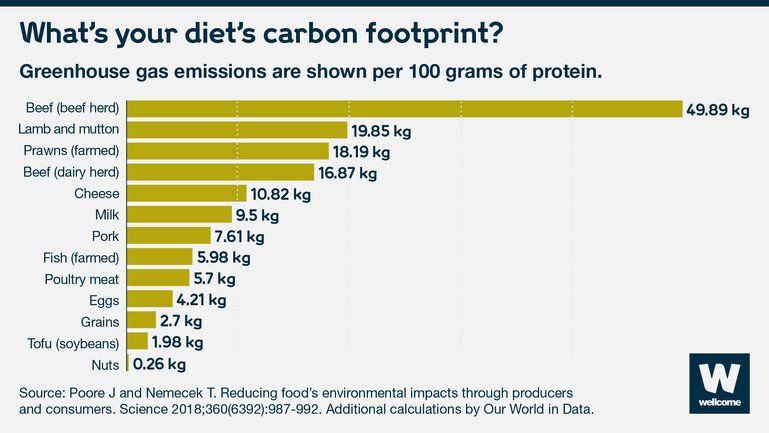

Meat and dairy products have some of the largest climate impacts, and it’s projected that demand for these foods will grow by 68 percent over the next three decades.

Greenhouse gas emissions are shown per 100 grams of protein across a global sample of 38,700 commercially viable farms in 119 countries. Greenhouse gas emissions are measured in kilograms of carbon dioxide equivalents (kgCO₂eq) per 100 grams of protein.

Source: https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/ghg-per-protein-poore

Wellcome

If regions with diets high in calories and animal-sourced food eat more plant-based foods, it will significantly help lower emissions, reduce mortality from diet-related risks and improve health.

What’s more is that there are 14,000 existing edible plant species with excellent nutritional profiles that we could tap in to. But we currently use less than 200. Diversifying our crops will also help to protect our food from floods, droughts and diseases.

2. Encourage sustainable agriculture and food practices

There are several opportunities to make agriculture and food processes more climate resilient.

One intervention is improving soil quality. Healthy soil stores carbon and can reduce emissions. It also aids drought and flood management and increases crop productivity and resilience.

Another example is selecting crop varieties that are high in nutritional quality and more resilient in extreme climate and weather events. Diversification could substitute nutrient-poor staples and complement actions to vary what we eat.

Meanwhile, cutting food loss and waste can help reduce hunger and save energy and water. Around 17 percent of all food worldwide goes to waste every year – and food waste is responsible for around 6 percent of global greenhouse gas emissions.

3. Increase investment in fair, science-based solutions

The effects of the climate crisis are not equally felt. The countries least responsible for it are the most vulnerable to its impacts and have fewer resources to act.

It’s critical that rich countries, who are the most responsible, step up and lead the transformation of our food systems in the mitigation of climate change. They should also support lower-income countries with the necessary finance and technology to adapt to more sustainable and climate-resilient local food production.

The world must take substantial, timely action now to cut greenhouse gas emissions and support a transition towards climate-resilient food systems.

More collaboration and investment are vital, and our actions must be backed by science if we are to avoid the worst-case scenarios of climate change and its impact on our health.

That’s why Wellcome is supporting research to urgently generate evidence through programmes such as Sustainable & Healthy Food Systems (SHEFS), Livestock Environment And People (LEAP) and the Food Systems Economics Commission. Because having better evidence on the nature of the problem and solutions will make us better placed to build a healthy, sustainable future for all.

We’re funding vital research into the impact climate change has on human health around the world, at national, regional and global levels. Explore our current funding call:

Advancing climate mitigation solutions with health co-benefits in low- and middle-income countries

This article was first published 7 June 2022.