Knitting to ease depression

During the Covid-19 pandemic, Jameisha Prescod turned to knitting when she felt overwhelmed by everything. Her self-portrait, 'Untangling', was taken during the forced isolation of lockdown and was one of the winners of the Wellcome Photography Prize. Here, she talks to us about the image, her own experiences of mental health and treatment, and why we should be joining up conversations around mental health.

My nan taught me to knit when I was eight or nine. I hadn’t done it for a while prior to the pandemic because I was so focused on work and all these other things that are in my life. When the Covid-19 pandemic hit, I found myself working a lot more than usual. Then sometimes a depression would start, or anxiety would come in and it could be quite overwhelming. So, in moments where I felt overwhelmed, I felt this urge to make something to take my mind off of it.

Knitting is a very repetitive action, and I think there can be something meditative in repetitive action. It helped take my mind off something while being productive.

Jameisha Prescod

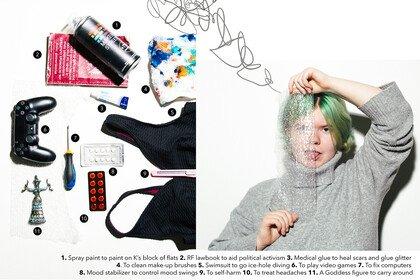

The isolation of lockdown exacerbated London film maker Jameisha Prescod’s depression, as she spent most of her time in the concentrated chaos of this room. “It’s where I work a full-time job, eat, sleep, catch up with friends and most importantly cry.” Before long, she felt like she was “drowning in the clutter”. For escape, she turned to knitting, which helps to soothe her mind. It may not be a cure, but it does at least put “everything else on pause” for a while.

Jameisha Prescod / Wellcome Photography Prize 2021

The image I submitted for the Wellcome Photography Prize is me knitting in a really messy room. I like to refer to it as documentary photography, even though it's a self-portrait. I see documentary as a representation of reality from the person’s perspective. This image is reality. The room actually was messy like that because of a period of depression. And I was knitting. The image documents something that I had been doing and it tells a story, but it was also something that opened up a vulnerability that no one saw.

Let's say you work from home or you're chatting with friends online. You can edit your background, just show a little corner or blur it. You can hide a lot of the truth that's behind the screen. This photo was a chance to show what was behind this constructed reality that I had set out for the people I was communicating with – whether that’s colleagues, friends or through social media.

It was hard to put it out. I found it quite embarrassing at first. I guess it's not seen as completely socially acceptable to have messy spaces like that. But I just think that people need to realise, actually, sometimes the mess in a room can be a representation of where your head's at, and there shouldn't be shame in it. If that's where you are, it's ok to be there. That’s why I submitted the image, to not only help myself, but by putting it out there I thought, maybe someone will see it and recognise themselves.

We don't always share these parts of ourselves, and I think sometimes when you put yourself out there and share vulnerability, other people feel seen and sometimes they're even willing to have that conversation and share that vulnerability back. I did have quite a few people message saying, ‘Oh my God, I'm literally in the same thing’. As a black Caribbean person, there's a big focus on cleanliness and tidiness, and you’re not supposed to show your home life, you’re supposed to keep that behind closed doors. Someone contacted me to say that the ‘fact that [I] showed that was kind of like, wow.’ It was nice also to have those conversations with people.

I do think that there are more progressive conversations online and offline about mental health. While there is more of an openness, what's also needed is more of an open conversation and something constructive in terms of how people can actually get help. We can have these conversations and that may help some people, others might ultimately need extra help or therapy or medication, and unfortunately, sometimes the resources are not always available for everyone. It's great that there's less taboo and stigma around these conversations and around people going to therapy, but we need to do more to ensure that our conversations with GPs (general practitioners) are just as open. For example, I've got lupus, and I don't have many conversations about my mental health with my lupus doctors. The fact that those conversations are not interweaved within the actual structures of medicine is an area that needs to catch up because otherwise, there might be a set of people that have these conversations, realise what they’re feeling isn't quite right, but can't take the next step to get help because they can't access it.

Jameisha Prescod is a London filmmaker and journalist, who lives with the long-term condition, lupus. She runs a popular Instagram account, You Look Okay To Me, which she calls “a digital space for the #chronicillness people”, as well as a Youtube channel of the same name.