How mental health ‘first-aid-kits’ are helping people cope

“If all systems fail you, and you have no supportive community to help you, where do you turn to?” Sebastian Mar photographed Russian women along with the mental health first-aid kits they have created to help them get through difficult moments.

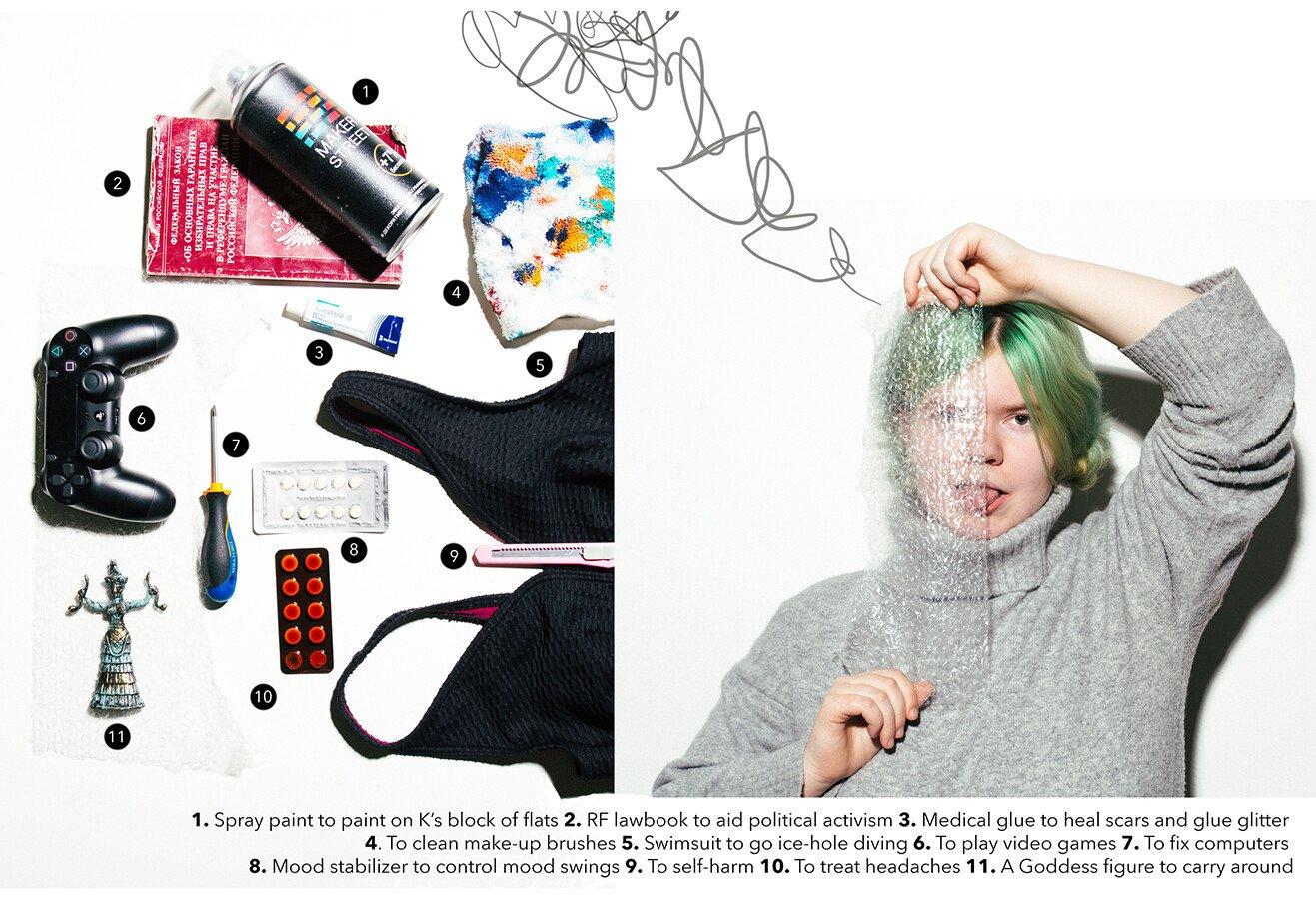

Moscow, Russia, 2019

Ksusha has bipolar disorder. She works as a computer technician at a liberal political party. Her hobbies are ice-hole diving and artistic makeup.

Sebastian Mar / Wellcome Photography Prize 2020

Here, Sebastian speaks to us about how mental health is viewed in Russia, their own experiences and why there’s power in objects.

How is mental health viewed in Russia?

In Russia, if people consider you to be ‘crazy’ then they think you should be locked up and kept away from society. And all sorts of things are labelled as ‘crazy’ in Russia, including child-free women, LGBT people, artists, and basically anyone who doesn’t fit in.

My grandmother was treated in a psychiatric hospital during the 90s.

Whenever she mentions this experience to me, she insists that she wasn’t like the other ‘psychos’. I often hear strangers use the word ‘schizophrenic’ to denote a person who acts aggressively or impulsively.

I myself don’t have to deal with mental health stigma very often, at least not directly, because I am very privileged to have the ability to select the social circles I move in. I think most of my friends have their own mental health struggles, and quite a few of them are mental health activists, artists who work with this subject matter or are open-minded mental health professionals. But step out of this progressive bubble and you meet people who haven’t even come across the term ‘mental health’.

Each kit is so unique and personal to the person who has put it together. Were you ever surprised by the breadth of things people used to support their mental health?

I do not think I was surprised by the things I saw, partly because of what my own mental health issues have taught me, ever since my first mental health crisis at 17.

All of us who struggle with mental health need the same things: comfort, safety, peace of mind and a sense of togetherness, and that is what the objects I saw communicated to me.

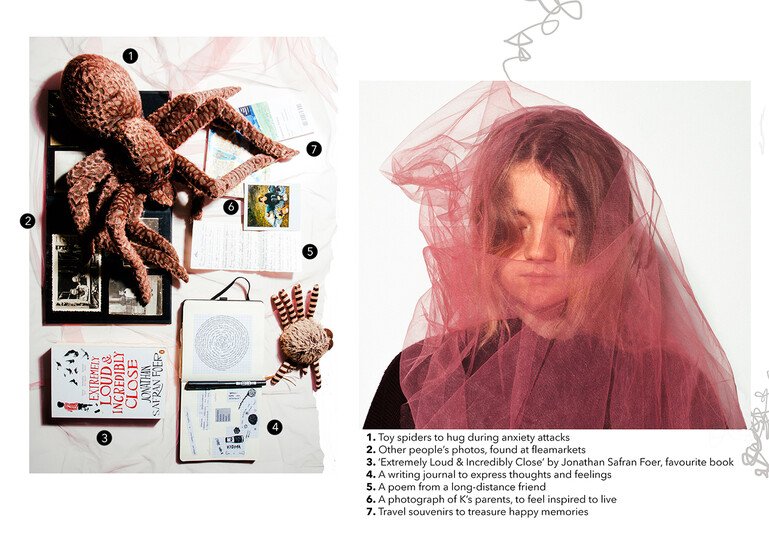

Moscow, Russia, 2019

Katerina has generalised anxiety and mood disturbances. She is a freelance blogger and writer, and a student of literature.

Sebastian Mar / Wellcome Photography Prize 2020

You see the mental health kits as ‘a manifestation of hope and resourcefulness’, why do you feel that way?

Affordable, professional mental health care administered without judgement, sexism and homophobia is hard to access in Russia. People are wary of state clinics that provide free mental health support because they are afraid to be put on the official register of people with psychiatric illnesses and/or addictions. This register is shared with many state institutions and being on it can impact your ability to get a job, a loan, or a driving licence, even if your ailment isn’t debilitating. It is also very hard to go off this register once you are on it. Meanwhile, private mental health care is terribly expensive. If all systems fail you, and you have no supportive community to help you, where do you turn to? Having a physical toolkit that you can grab in a crisis can help alleviate that horrible feeling of having nowhere and no-one to turn to. Knowing there are ways to help yourself, even when there might be nowhere to go to receive help, does give me hope.

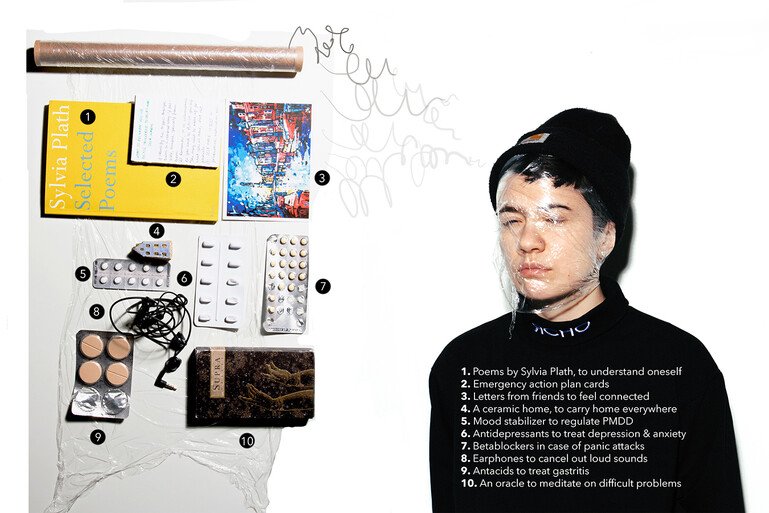

Moscow, Russia, 2019

Seva has chronic depression and anxiety disorder. She is a fashion photography student and poet.

Sebastian Mar / Wellcome Photography Prize 2020

Can you describe your own mental health kit?

It’s a combination of traditional treatments, such as beta-blockers, prescribed to help with panic attacks, and mood stabilisers, and things that have a personal significance to me. One is a pack of oracle cards, which work similarly to tarot. I turn to them for advice when I am very anxious and feeling that everything in my life is going badly. Another item is a small ceramic house figurine from Lviv, Ukraine, which my partner gave to me at the beginning of our relationship. I travel often and take this house, a symbolic representation of the home we have built together, everywhere I go. And even at home, I sometimes hold it in my hands to feel grounded when I am anxious. I think by creating a ritual around this simple object I’ve turned it into a powerful artefact that can have a special effect on me.

Your images turn complex issues into strong visual narratives. Were you hoping that they would spark discussion about what helps others?

I wasn’t focused on sparking discussion, because I didn’t think it would reach that many people. I was mostly hoping to ease the feeling of isolation that so many women with mental health struggles experience and highlight that even without access to professional medical health there may be alternative ways to help yourself. I was initially more focused on empowering the affected sufferers. However, when I participated in the Wellcome Photography Prize, I realised I could bring international attention to mental health help in Russia and women’s struggles specifically.

Moscow, Russia, 2019

Polina has chronic depression, anxiety disorder and sensory processing disorder. She is a contemporary artist.

Sebastian Mar / Wellcome Photography Prize 2020

Why is photography an effective medium for battling prejudice and distrust?

People trust what they see better than what they read or hear. A photographic image can be very precise and concrete, and yet also open to individual interpretation. For example, a portrait of a psychiatric patient communicates to me that people with a particular condition exist, that they do not look like monsters, that they are recognisably human, and whatever emotion I see on their face, it is an emotion I have experienced myself. But also, through empathy, I can make this image about myself, project my own experiences, dreams or fears onto it, and through that build a personal connection to what I have seen, which can be very helpful if you are looking to interest or educate people on a particular topic.

Do you see the narrative around mental health in Russia changing?

In the liberal social circles and media, yes. I see that conversations about mental health are becoming more nuanced and intersectional. Just today I saw a popular local fashion magazine post an article about the term ‘trauma’, explaining how to differentiate difficult experiences from those that leave long-lasting scars, and giving examples of effective treatments. Terms such as ‘toxic partner’, ‘abusive relationship’ and ‘body shaming’ have also entered the Russian vernacular and can often be heard in younger women’s discussions of mental health.

Influencers speak about the importance of self-care and the ties between the productivity cult and capitalism. However, I don’t think this is reflective of Russia as a whole. That fashion magazine is read by a few thousand, not millions and most mental health institutions in the country still have abhorrent conditions and treatments that aim to torture, not heal. If the narrative is changing, the route of this change is not a straightforward one.