It's time to fix the antibiotic market

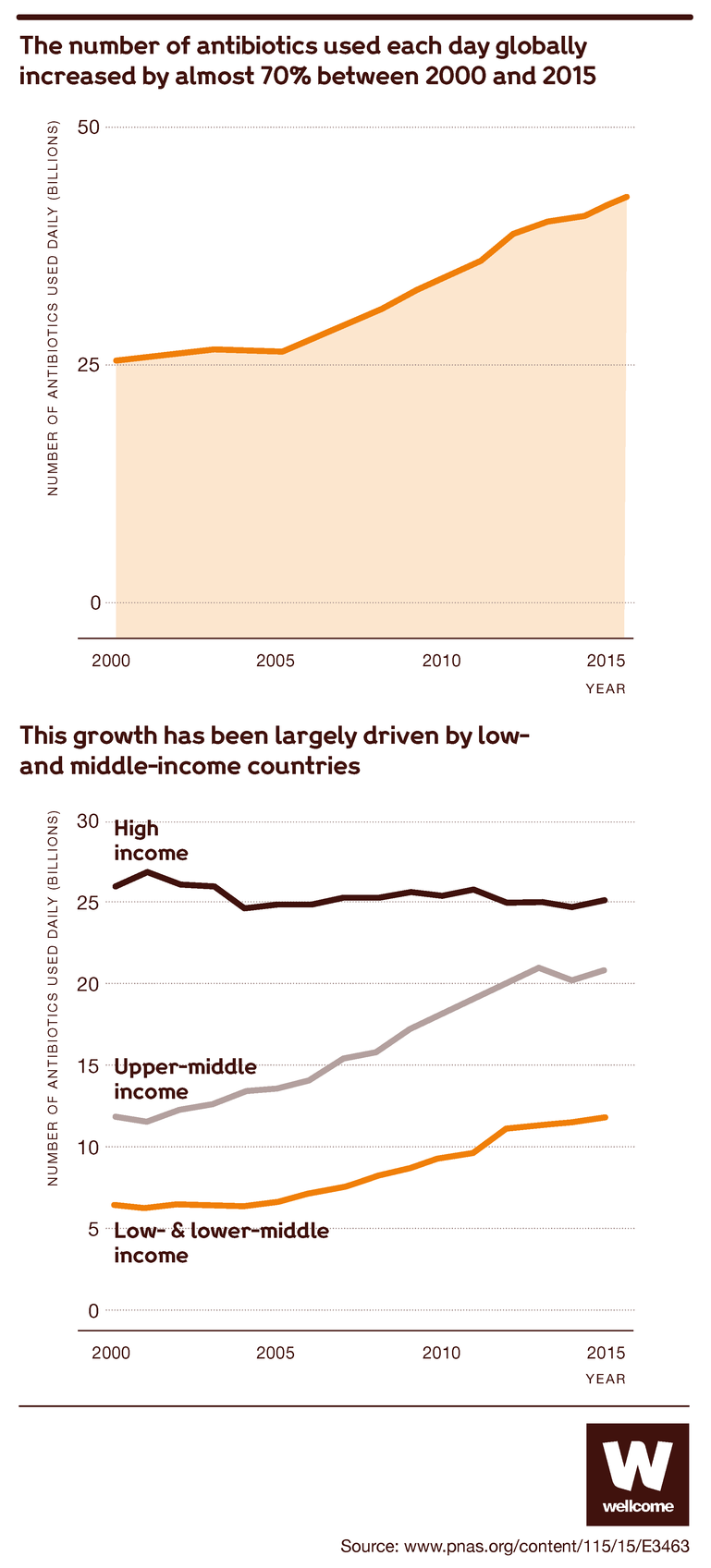

We need to keep developing new antibiotics to make sure we can keep protecting ourselves from ever-evolving bacteria. But the antibiotics market is faltering, as economic disincentives make it impossible to get the innovations we need. Governments, pharmaceutical companies and philanthropy must act now to reform the market and safeguard a sustainable supply of these lifesaving drugs.

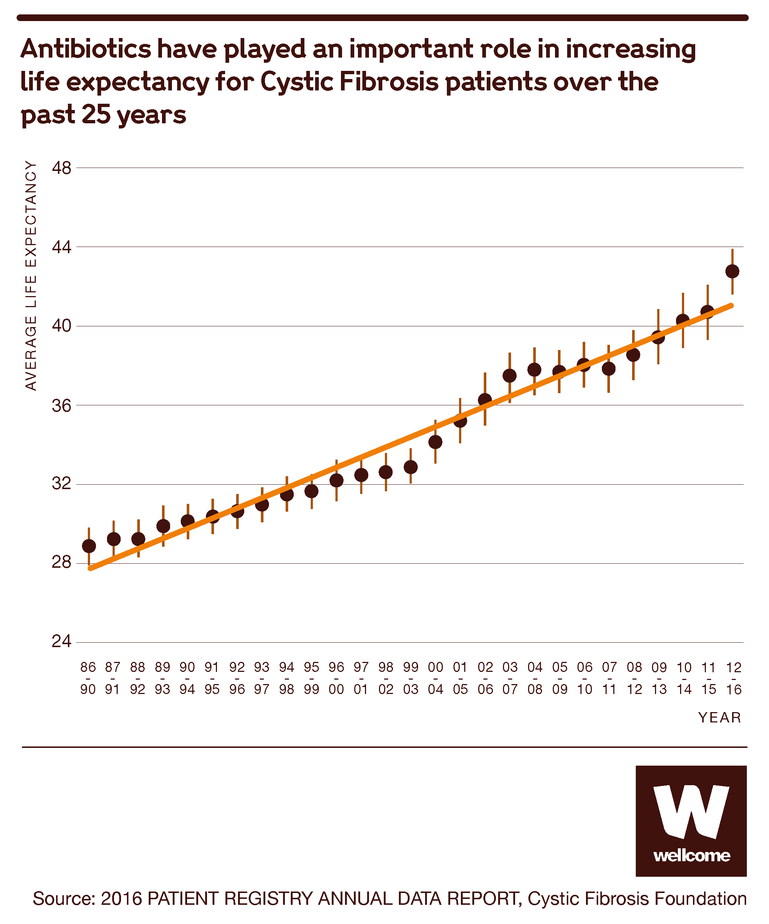

Antibiotics may be the biggest success story in the history of medicine. Since Alexander Fleming discovered penicillin, many other drugs like it have been developed, with the result that once-deadly bacterial infections are now easily cured.

This medical revolution has extended well beyond the treatment of infections, whether minor ailments like tonsillitis or serious diseases like pneumonia.

Source: 2016 PATIENT REGISTRY ANNUAL DATA REPORT, Cystic Fibrosis Foundation

Antibiotics have made many medical procedures much safer too. Any surgery – from a caesarean section to a hip replacement to an organ transplant – can expose you to infection by opportunistic bacteria. If you have cancer, chemotherapy will weaken your immune system, putting you at greater risk. And even minor cuts can expose you too.

Against all of these dangers, antibiotics can provide a vital safety net.

Source: Stemming the Superbug Tide, OECD Health Policy Studies

It’s no exaggeration to say that antibiotics are the foundations of modern medicine. But these foundations are in danger of crumbling.

Bacteria change, and so must we

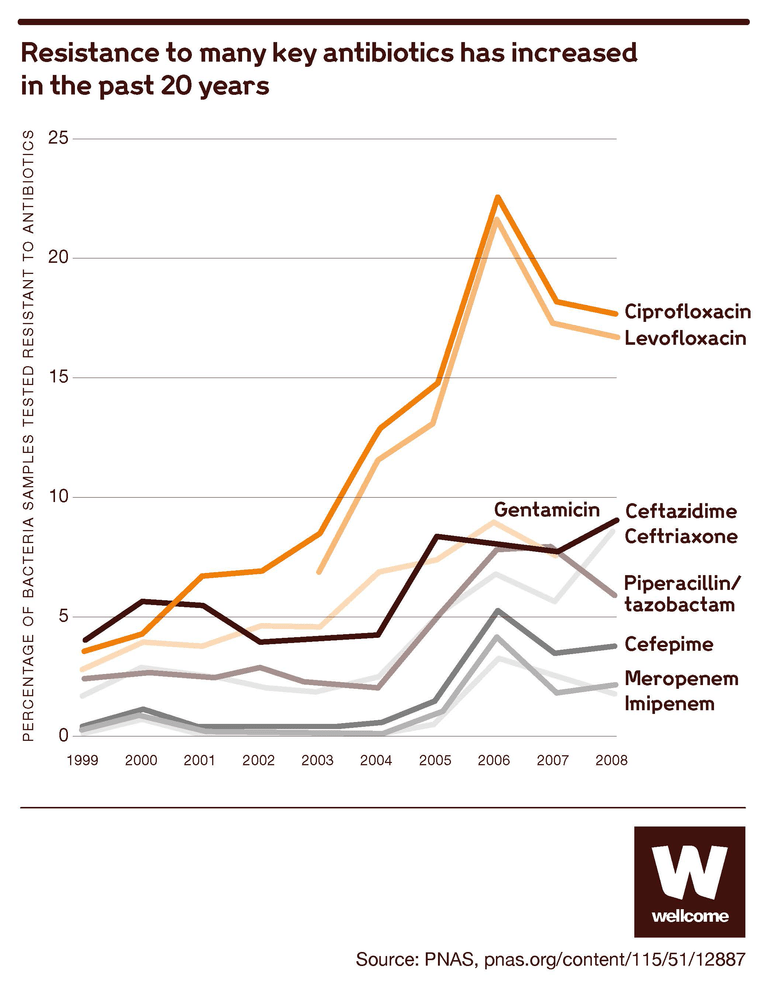

The problem is simple: bacteria evolve. They reproduce and mutate at an incredible rate, and some of these mutations will help them to resist the antibiotics that we use to kill them. And whenever scientists produce a new antibiotic, it’s only a matter of time before bacteria find a way to beat it.

This has always been true – Fleming saw it happen in his lab – and the solution has always been the same. We need to use the antibiotics we have sparingly, but we also need to keep developing new ones.

Source: Technologies to address antimicrobial resistance, PNAS

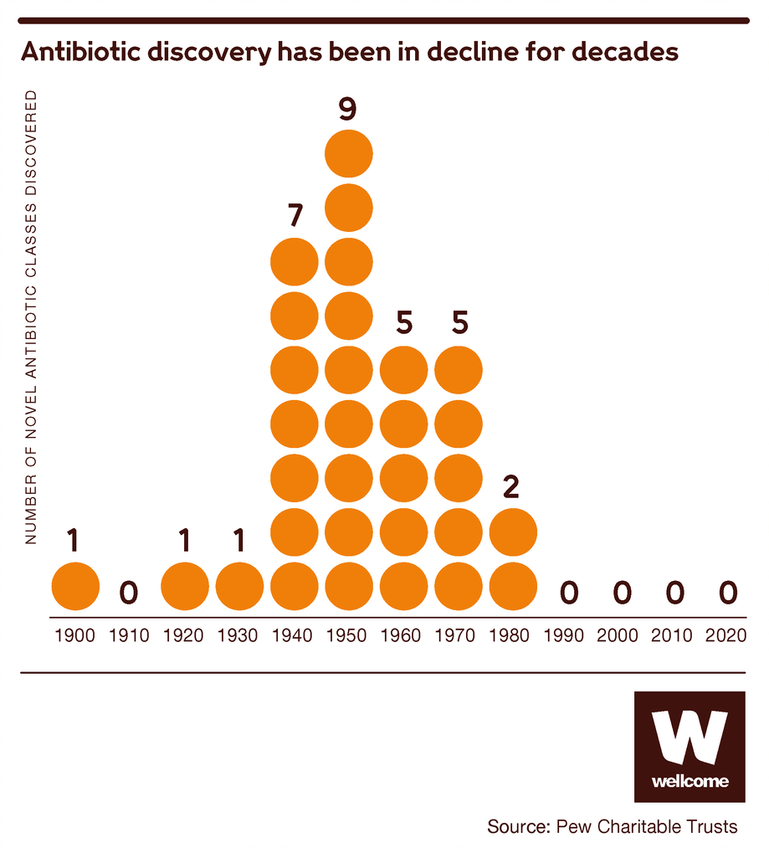

For much of the 20th century, we were very good at one half of the puzzle, developing new antibiotics. Scientists equipped doctors with a formidable range of antibiotics, regularly updated – so, if one of them failed a patient, there were plenty of other options.

But in recent decades we’ve slowed down. New antibiotics are fewer nowadays, and they’re less innovative too: the limited number brought to market since the 1980s has been a variation on drugs that already exist. They’re still useful to have, but their similarity means they pose less of a challenge to bacteria that can already resist the old ones.

Source: Pew Charitable Trusts

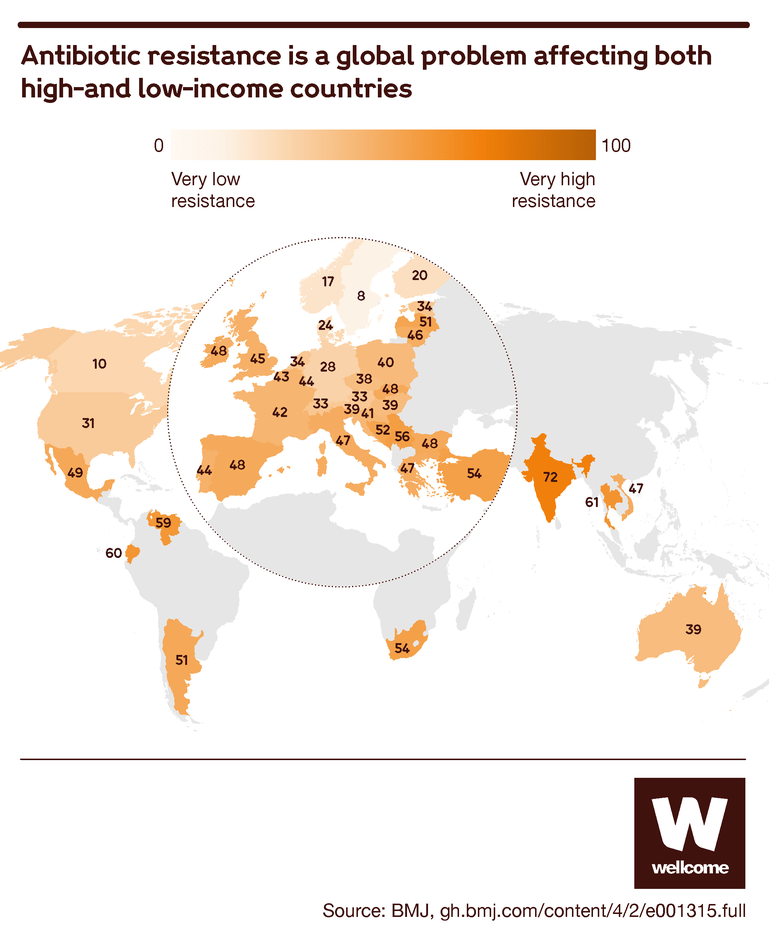

And the bacteria keep evolving, meaning we see continuous new trends of resistance. This is being accelerated by our collective human action and use.

This means that common infections and injuries that we’re used to seeing as minor inconveniences are once again becoming life-threatening, and the risks that accompany many medical procedures are growing.

Source: Tracking global trends in the effectiveness of antibiotic therapy using the Drug Resistance Index, BMJ Global Health

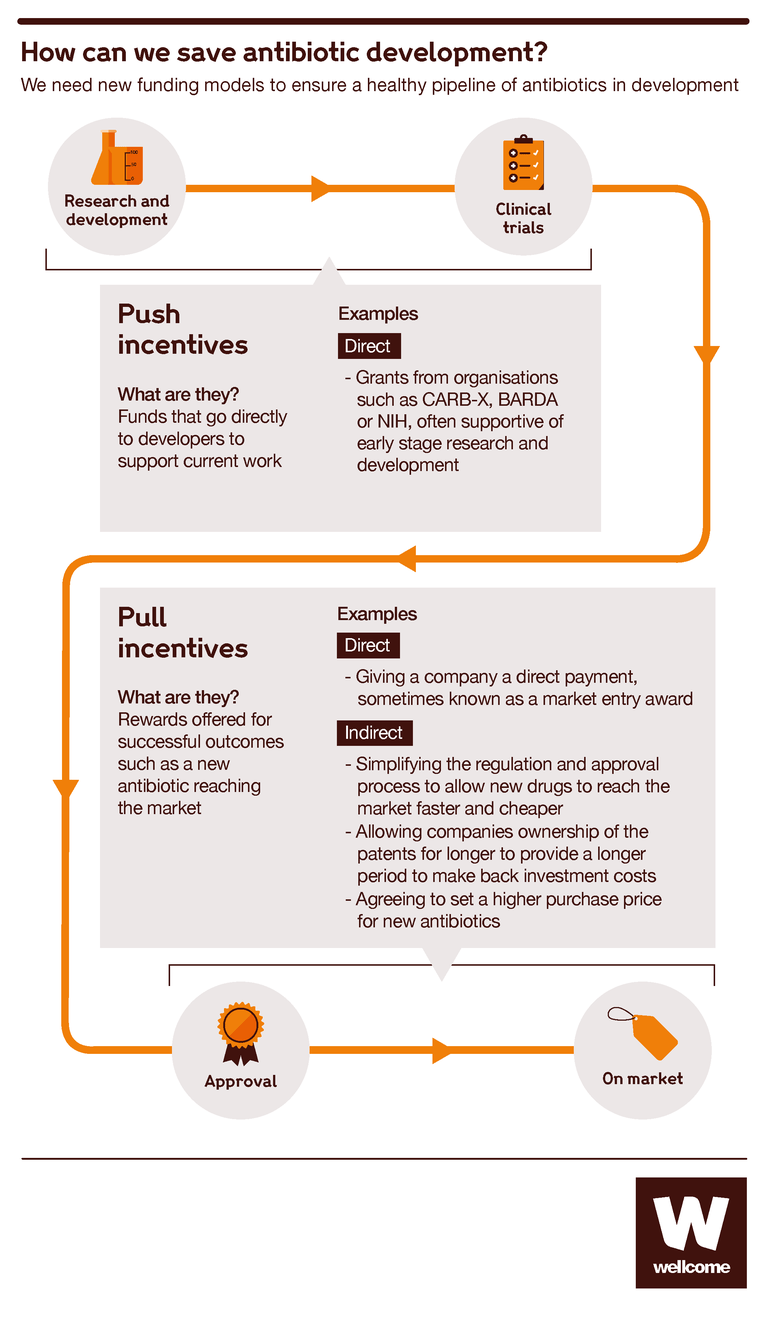

How to develop an antibiotic – and how to fail

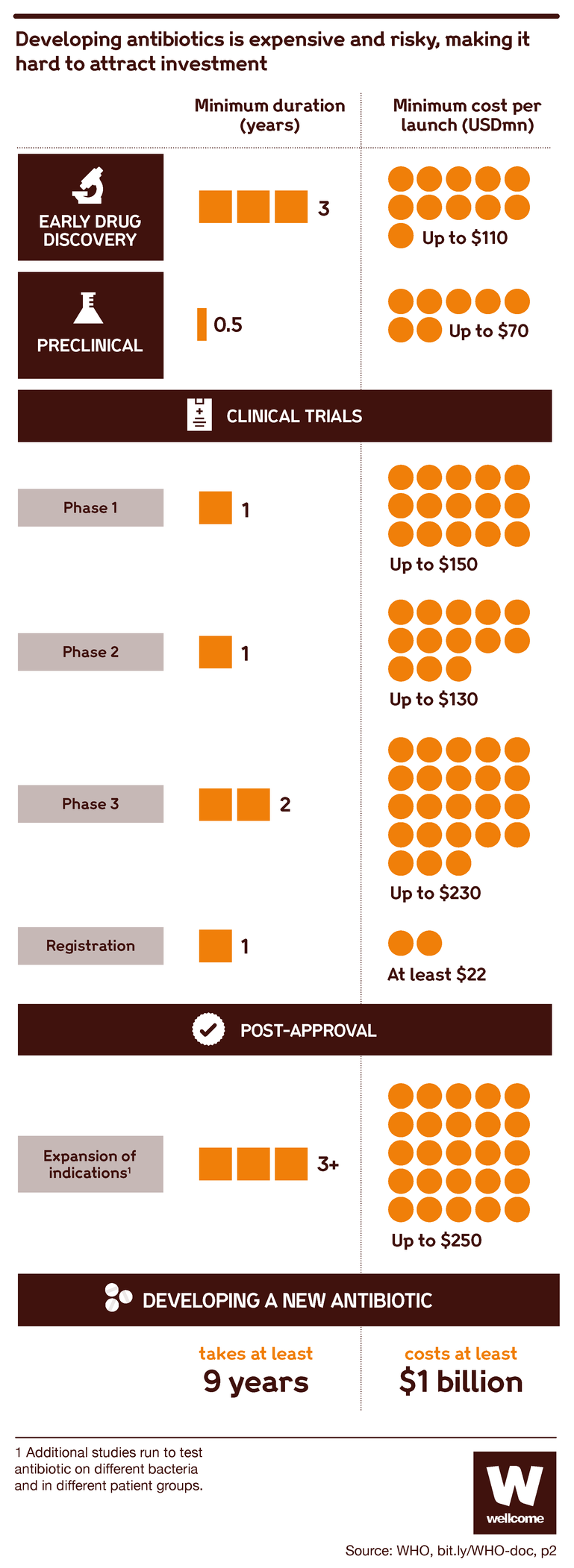

Producing a new antibiotic is slow and expensive work. It typically takes 10–15 years and over $1 billion.

First, you have to identify a substance that you think might be worth looking into. Then you go through a period of lab testing to study its properties and effects, after which you test it in animal models.

Then you start on the clinical trials with humans, usually in three phases: small phase I trials to see how safe it is, including at different dosages; larger phase II trials to assess safety more thoroughly and see if there are positive effects of the new antibiotic; and even larger phase III trials to compare it with existing treatments and see how long any positive or side effects may last.

Then you need to get government regulators to approve your drug.

And after that you can start marketing it to doctors and health services so that they can start using it to save lives – except that more often than not, you don’t make it that far. Your antibiotic can fail at any step of the process, and then all you have to show for your work is a detailed map of a dead end.

Source: Pulling Together to Beat Superbugs, World Bank Group

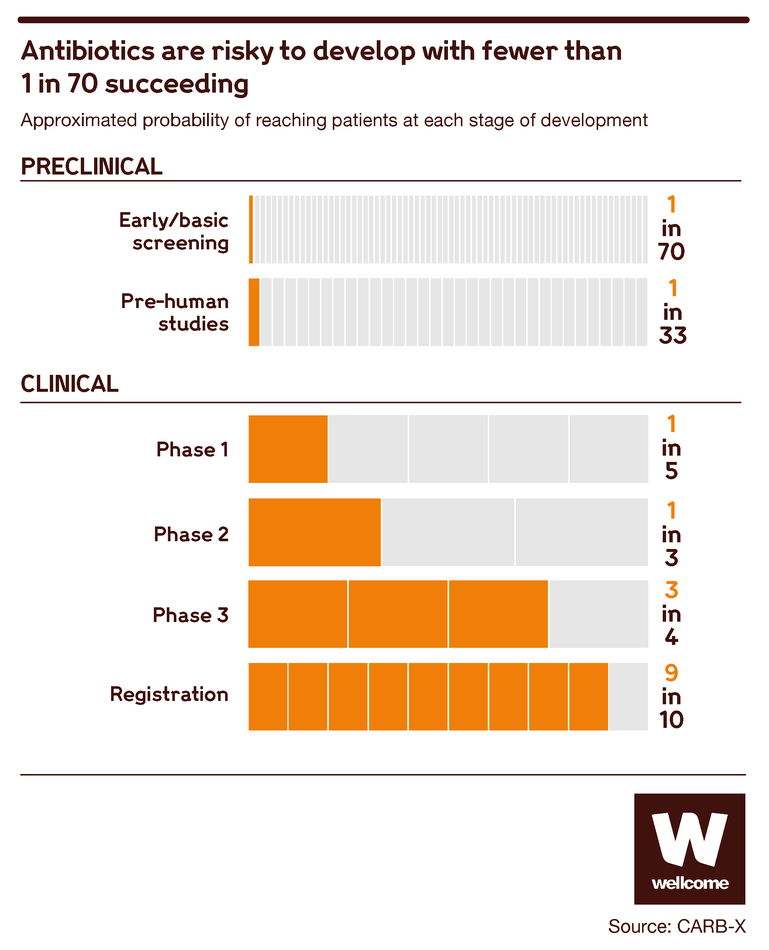

From the beginning of the development process, your candidate has a 1 in 70 chance of reaching market.

Though chances increase as drugs progress through the development process, this shows that antibiotic development is a risky business. If you don’t have the kind of deep pockets that can tolerate a high failure rate, you’re going to think twice before getting involved at all.

Source: CARB-X

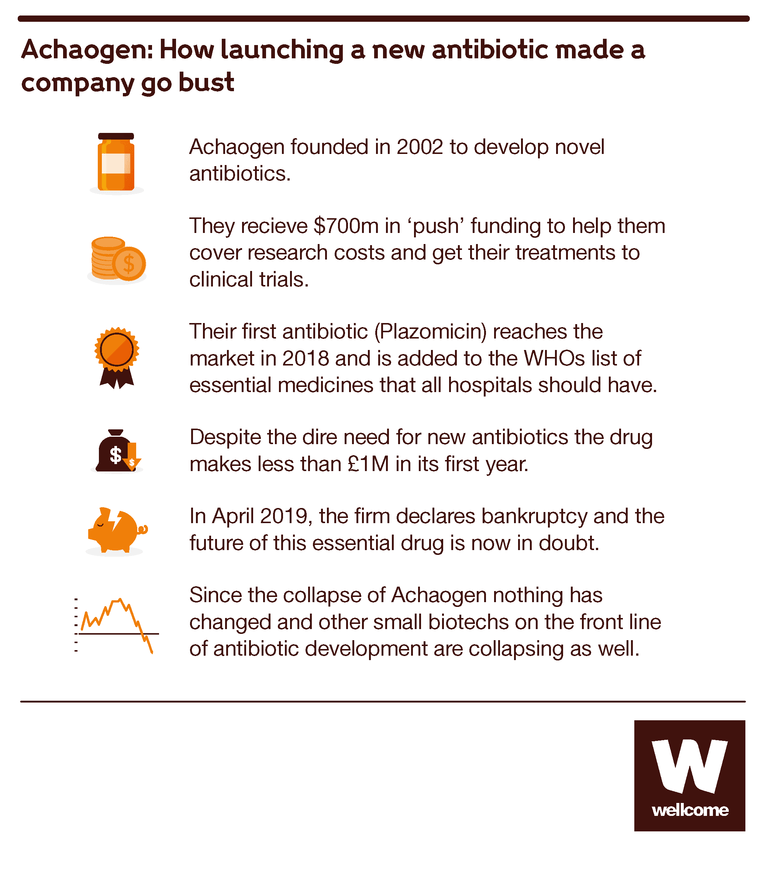

Another problem is that even if you succeed, you can still fail. That was the fate of a company called Achaogen.

Achaogen was a small pharmaceutical start-up, founded in 2002. It put together a strong team of scientists, it got backing from government and philanthropic funders, and after 15 years of hard work it released its new antibiotic, Plazomicin, onto the market. Plazomicin was first approved to treat urinary tract infections, one of the most common drug-resistant infections.

But Plazomicin’s sales figures were terrible: less than $1 million in its first year, nowhere near enough to recover the huge costs of its development. By comparison Humira, a treatment for arthritis, saw over $19 billion in sales in 2018. Achaogen’s stock plummeted, and the company filed for bankruptcy in 2019. A scientific success became an economic failure.

How economics works against antibiotic developers

How could such a thing happen? If new antibiotics are such prized resources, surely the world’s health services would all rush to buy one?

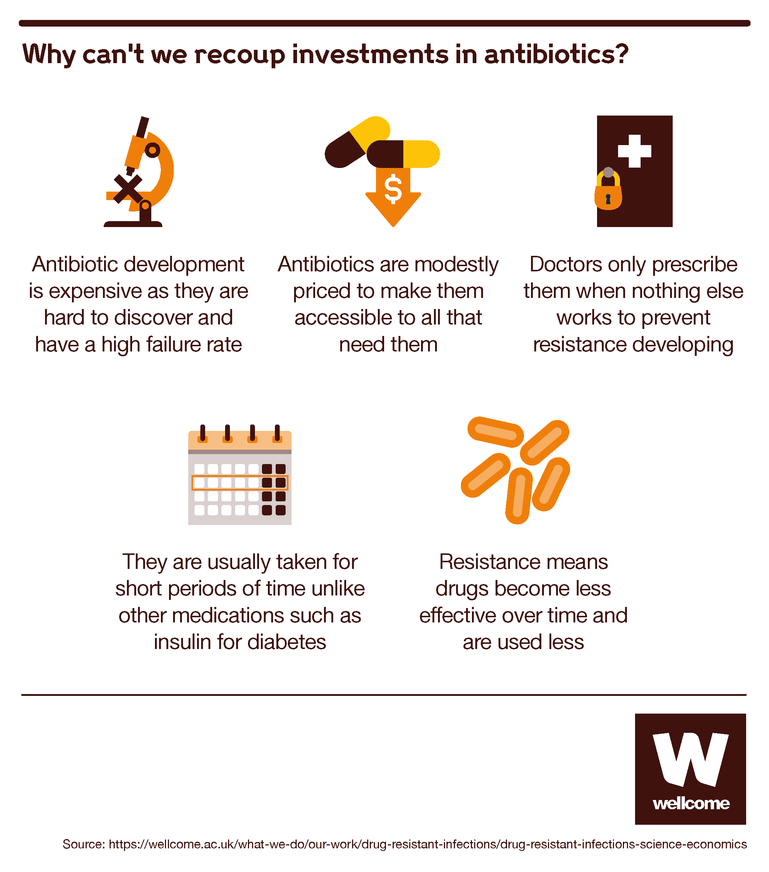

Unfortunately, it’s not that simple. Use of new antibiotics is restricted to last resort cases in order to slow the development of resistance. This in turn causes lower demand, which means limited sales and lower prices relative to many other drugs.

Imagine you’re a doctor. You want to protect your patients and give them good treatments, but you also want to protect your ability to keep treating them in the future. And you know that the more people use antibiotics, the more likely bacteria are to develop resistance to them. So you prescribe them sparingly, only when really necessary, and only in small quantities.

This is all the more true for new antibiotics, which bacteria haven’t yet learned how to resist. Those are the drugs you hold back as a treatment of last resort, for when older (usually far cheaper) antibiotics have failed.

This makes good sense medically, but the economic result is that a new antibiotic isn’t likely to produce much profit for the company that has invested so much in creating it.

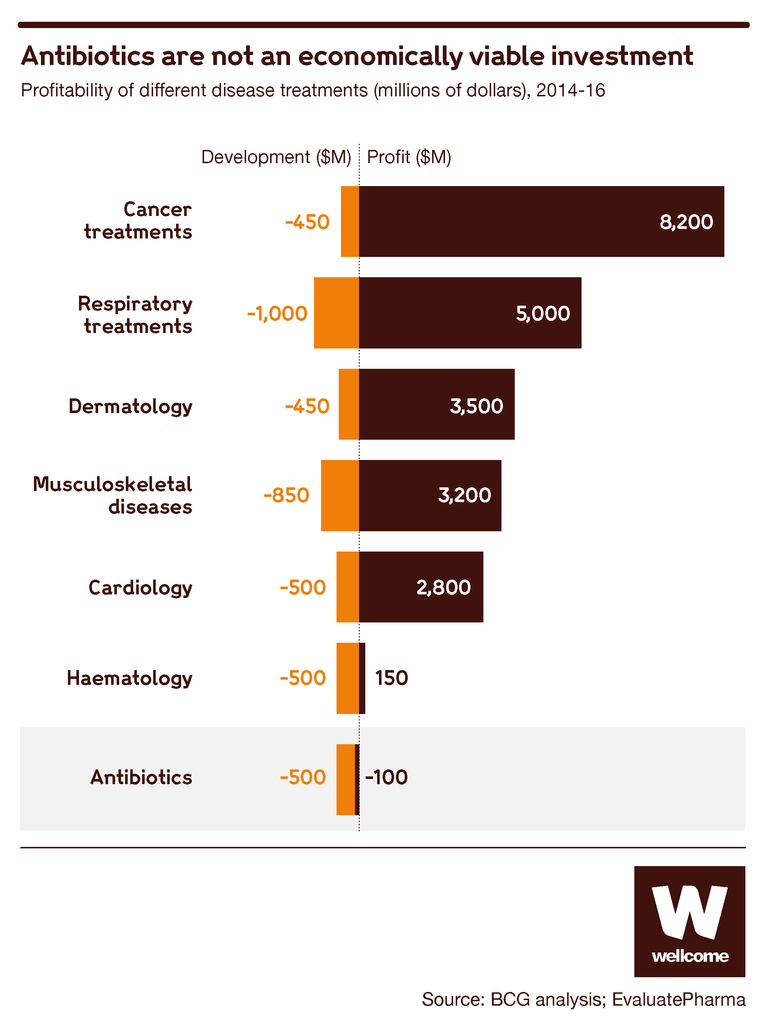

Source: BCG analysis; EvaluatePharma

In the face of these financial risks, even the giants of big pharma are deserting the field.

Back in 1990 there were 18 global pharmaceutical companies developing antibiotics. Today there are just five. And the number of new antibiotics being approved has also fallen, from three a year in the 1980s, to two a year in the 1990s, to less than one a year since the turn of the century.

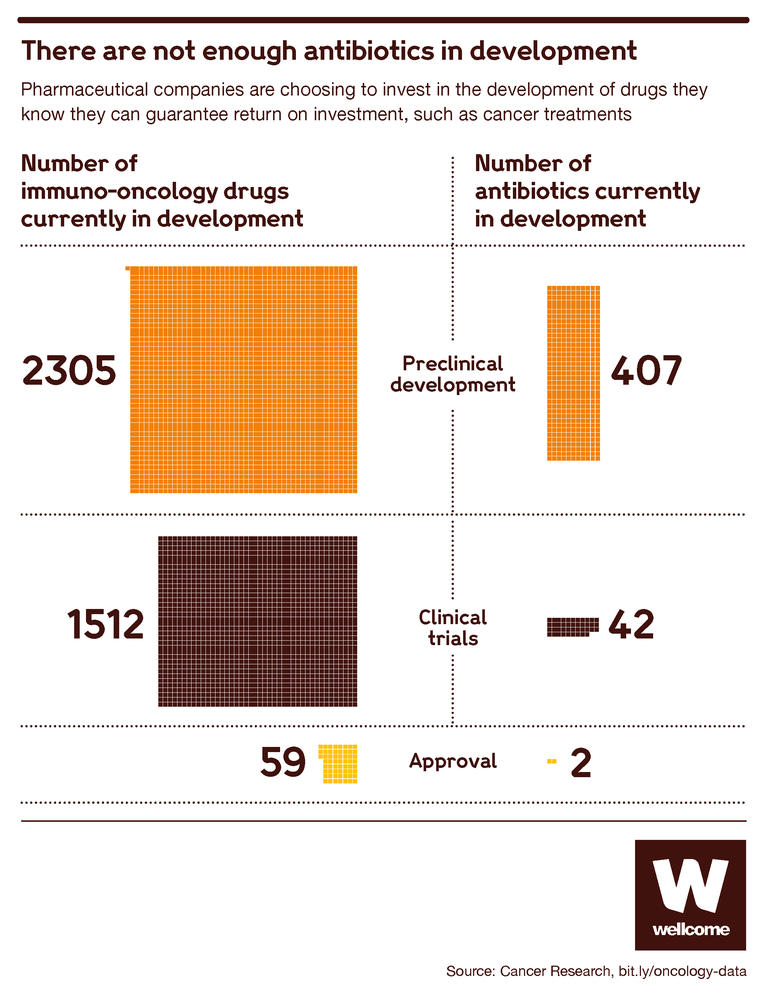

Today, the antibiotics development market is dominated by small and medium-sized enterprises, as well as a fair number of academic institutions. They’re doing good work, but most of it is still in the early stages.

Source: Immuno-Oncology Landscape, Cancer Research Institute

The high failure rate in antibiotic development means that most do not progress to testing in humans, only about 10 percent. This leaves just 40 antibiotics in clinical trials globally, and it’s these later-stage trials that are the most expensive part of the process, requiring big pharma resources and infrastructure.

These organisations will not have the resources to tolerate the inevitable failures, to steer the more successful discoveries through to release and, ultimately, to survive long-term if sales are disappointing.

New ideas to reform the antibiotics market

The antibiotics market is broken. To make sure that all that scientific talent can produce lifesaving results, we need to rethink and re-engineer how companies are reimbursed for their products.

There’s already been some success on this front. In recent years, the early stages of the antibiotic development market have been reformed to encourage more new entrants, thanks to initiatives like CARB-X.

CARB-X is a partnership between governments and philanthropic organisations including Wellcome, providing funds to foster innovation in preclinical development and phase I trials. It provides the funding that small companies need to make breakthroughs at a stage when having a marketable product is still a dim and distant prospect. It has invested over $240 million in 64 projects that include 16 potential new classes of antibiotics. Yet, all of this investment and progress is at risk of being lost.

Promising results at these early stages are no guarantee of ultimate success, and that’s why we need to turn our attention to the later stages.

Several options are being discussed by governments, businesses and philanthropic funders around the world. Here are a few of the ideas:

- Market entry rewards. These would be lump-sum payments to companies that successfully develop new antibiotics, giving them an immediate financial return to recoup some of the costs of their efforts. This was recommended by Jim O’Neil’s Review on Antimicrobial Resistance, and governments are considering it but have not yet taken action.

- An insurance premium model. If governments committed to making fixed annual subscription payments to pharma companies in return for access to valuable antibiotics once developed, this would give those companies a reliable flow of income to support their ongoing work in the field. The UK government is the first to launch a pioneering scheme like this, agreeing to pay pharmaceutical companies upfront for their work.

- Working together to simplify trials. Clinical trials are complex and expensive, so establishing enduring clinical trial networks could save time and costs. These would enable companies to get going quickly without having to set up new study sites every time. The networks could also share control groups and data from previous trials. Wellcome and others are recommending this approach as it has worked well to reduce the costs of trials for TB, HIV and malaria drugs.

So there are plenty of ideas for improvement. They might not all turn out to work as hoped, but given that the current market is failing for certain, it’s vital for all our health that we start putting innovations into practice. The bacteria that threaten our lives are constantly evolving, and so our economic models must evolve too.

The private sector cannot save the antibiotics market on its own. Nor can governments. Nor can philanthropic funders. All need to work together to safeguard the world’s supply of new antibiotics and make sure that modern medicine can keep saving our lives.

The recent launch of the AMR Action Fund is an important milestone, with major commitments by the pharmaceutical industry to fix antibiotic development. It is a nearly $1 billion pharmaceutical industry-led investment fund that aims to bridge the funding gaps facing antibiotic developers as they head into later-stage development, and ensure new treatments for drug-resistant infections are available for the patients who need them the most. It aims to bring 2-4 new antibiotics to market in the next 15 years and is being funded by 23 major global pharmaceutical companies.

This is exactly the kind of ambitious action that is so necessary to save antibiotics. Yet even this vast sum of money and feat of industry cooperation will not be enough to sustain us long-term. Despite the scale of commitment, it cannot offer more than a temporary bridge for some of the most promising antibiotic innovations emerging over the next decade. We now need governments to do more to permanently fix the system as only they can deliver truly sustainable solutions via improved reimbursement and a stabilised market for antibiotics.

In 2020, people’s focus is understandably on COVID-19. But other health risks haven’t gone away: antibiotic-resistant infections continue to kill people in every country of the world, day in, day out, and almost all hospitalised COVID-19 patients require antibiotics as part of their treatment. And that death toll will only accelerate – unless we act to stop it. One of the lessons we should learn from this year is that it’s better to find solutions before we reach the point of emergency.

Let’s work together to write the next chapters in the success story of antibiotics.

It's time to fix the antibiotic market. Governments must act now to safeguard the world's supply of new antibiotics #StopSuperbugs – says @wellcometrust

Related content