The climate crisis worsens the threat of antimicrobial resistance in several ways. Temperature is intimately linked with bacterial processes and infections.

As temperatures warm with climate change, bacterial infection rates may increase and diseases can spread to higher altitudes and latitudes where they were not previously found. Bacteria can also grow and reproduce faster and swap genes with one another (a process called horizontal gene transfer). The faster this occurs, the more likely bacteria are to develop antibiotic resistance.

Higher temperatures may also cause drought, which results in water shortages and a lack of food. This can cause malnutrition, with children most vulnerable, lowering immunity and the ability to fight off infections. Infections can spread quickly in these conditions and could become drug-resistant, with mortality rates likely to increase.

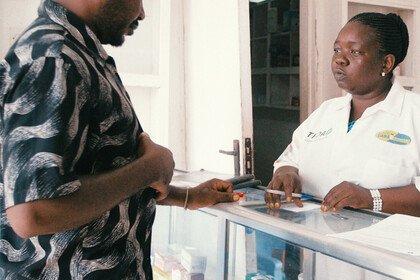

Flooding and drought can lead to displacement, overcrowding and a lack of clean water. Poor sanitation and reduced access to treatment and medicines in disasters like these can cause rises in infections that can become drug-resistant.

These extreme conditions, fuelled by climate change, will also put increasing pressure on farmers and livestock producers. Antibiotics are often used in food production and could further increase to protect diminishing crop and animal yields. The overuse and misuse of antibiotics in farming is increasing the development and spread of drug-resistant infections in humans and animals.