Episode 6: How can we revitalize informal settlements?

Around the world, roughly one billion people live in informal settlements. These communities are especially vulnerable to extreme weather events. Alisha speaks to Professor Karin Leder about projects in Indonesia and Fiji that are collaborating with local communities to address these challenges.

Listen to this episode

Losalini Malumu 00:05

Sharing my experience with them helps build trust with the community members. They start feeling that it's their system and that's something that they need to take ownership of, which is very empowering.

Alisha Wainwright 00:22

Welcome to When Science Finds a Way, a podcast about the science changing the world. I’m Alisha Wainwright, and on this series I’m meeting with scientists and researchers who are actually making a difference, as well as the people who have inspired and contributed to their work.

This episode is about water, sickness, climate change – and toilets.

But it’s also about informal settlements. You might know them as slums or shanty towns. These words can carry a negative association – but for about a billion people, these places are home.

Ibu Ina Rahlina 01:06

The family and the neighbourhood is very close. We help each other, because we’re very close with our neighbours.

Alisha Wainwright 01:14

But, as you’ll hear – these informal settlements just don’t have robust water infrastructure. And when you don't have reliable drainage, or waste disposal, you’re especially vulnerable to the severe weather events that are increasing in frequency due to climate change.

Heavy rains and floods can cause havoc anywhere. And in informal settlements, they can lead to multiplying problems, that you might never think of if you’re used to living with water systems that just work.

For this episode, I spoke with Professor Karin Leder, who’s the Head of Research at RISE. That’s Revitalising Informal Settlements and their Environments. They work in informal settlements in countries like Fiji and Indonesia. And, just like their name suggests, – they’re partnering with communities to address these problems – in a really interesting combination of a research study and a building programme.

We’ll hear more about that – but the important word there is “partnering”. Because this is not an attempt to bring in out of towners to fix things and then just go away. It’s about working with residents, empowering them – and listening to them – to develop ongoing, sustainable solutions.

Professor Karin Leder 02:38

Right from the beginning of RISE, we have been very clear that we're not doing something to communities, we're doing something with communities. And it’s up to the community to decide how it will work best for them.

Alisha Wainwright 02:51

And those are some of the voices you’ll hear in this episode. They’re RISE employees, AND residents of informal settlements, bringing their lived experience to the project. And – on top of some great recordings from around their communities – they also gave us insight into their lives, and how the RISE approach is working.

To start off with, here’s Karin explaining what an informal settlement is…

Professor Karin Leder 03:27

We're talking about settlements that weren't planned by governments and therefore don't have the infrastructure that governments usually give to communities. So they are settlements that have been built by residents on land that often doesn't have formal tenure. Often doesn't have formal infrastructure, do not necessarily receive piped water, or sanitation services, or main roads or any kind of drainage systems. Often don't have their litter, their hard waste picked up. They are just not receiving the services that governments give to communities that are formalised, that are part of what's seen as the government's responsibilities. These are people who - often because they've had nowhere else to go - have created their own communities on land that perhaps no one else wants, but it does make them vulnerable because they - there often isn't security in either the kind of type of settlement that they're living in, it often is land that's vulnerable. but also in their ownership of that land.

Alisha Wainwright 04:42

To get a firsthand account of life in an informal settlement, we spoke with Ibu Ina Rahlina. She works for RISE, and grew up in Mallenkiri settlement in Indonesia. She began by telling us what she liked about her home.

Ibu Ina Rahlina 04:59

46 years ago the atmosphere in Mallenkiri settlement was like a village. As far as you can see, you will see trees and rice fields. At that time, there were no fences in the settlement. Ornamental plants such as hibiscus were planted in front of the house and became a fence, a barrier between houses. The road is not paved, only dirt. If it rains, it will be muddy or you will find puddles. Livestock such as cows, buffaloes, horses, goats, ducks, and chickens roam the streets.

I like life in informal settlements, because your family and the neighbourhood is very close. We help each other, because we’re very close with our neighbours. And also the people help each other. So I like it, yeah.

Alisha Wainwright 06:02

In researching, and in hearing that story, I had such an entitled perspective, which is, if there are people living in informal communities just move them to a place that is formal so that they don't run into these issues. But it's completely not acknowledging the fact that these are communities. People live here, they have families here, they have networks there, of support, beyond just infrastructure. And it's, it requires a - looking at the community and trying to service them rather than prescribe what we think we should do.

Professor Karin Leder 06:39

That's absolutely correct. And for many of the people who live in informal settlements, it's multi- generations of their families who have lived there, and they expect that it will be many more generations that will continue to live there. They see it - as you said - this is their homes, and they want to make their homes better. They don't want different homes.

Alisha Wainwright 07:01

One billion people on this planet live in these types of settlements. And in one of your countries, Indonesia, and I guess also Fiji, how many people percentage wise, live in those settlements?

Professor Karin Leder 07:16

Look, it varies in different countries. But overall, it's said that about 10% of the world's population lives in informal settlements. And that number is growing, and particularly urban, informal settlements are growing. And it's predicted that that number is going to be about five times as high, so maybe up to 5 billion people by 2050, which is just an incredible number.

Alisha Wainwright 07:41

So when it comes to the water systems in the settlements that are part of RISE, what exactly are the issues?

Professor Karin Leder 07:49

In its basic form, a water system delivers water to households, but what we're talking about in RISE is really water and sanitation systems. And we see that the two things are linked. It's not only absolutely essential for everybody to have safe drinking water, when I mean, when I say safe, I mean water that's not contaminated with bugs that can make people sick. But it is also really important to have sanitation systems that are contained and controlled, so that the environments that people are living in, and the places where children go out to play, are not contaminated. In developed countries, what we have done is separate out our, where pipes that go into houses, you know, delivering clean water and pipes that come out of houses that take away, you know, our contaminated sanitation. But in informal settlements, it is at least gonna be decades, if not longer before those kinds of formal infrastructure, with big pipes, would ever reach these populations. And that's part of the problem of the people who live in these informal settlements- that, that they don't automatically get the infrastructure that the rest of us take for granted.

Alisha Wainwright 09:07

So they don't have the infrastructure. So, as it stands, what are they doing for drainage and wastewater disposal?

Professor Karin Leder 09:14

It's variable, but it's almost always inadequate and potentially problematic for the, for the inhabitants. So in some informal settlements and some of the houses within some of the informal settlements that we're working, people do have toilets. But their toilets are generally connected to septic systems that aren't well managed. So the septic waste ends up in the environment anyway. In some other circumstances, or some other houses, they are still practising open defecation, where, and they don't have toilets. But either way that faecal waste is getting into the environment, because it's either happening directly or through these not well managed septic systems. And we mentioned already that these communities, you know, often have poor drainage as well. So if you think about a septic tank, that's not well managed -

Alisha Wainwright 10:14

I mean, don't want to, but since we're having the conversation…

Professor Karin Leder 10:18

But if you, but you know, then there's flooding, and inundation, and other things that are superimposed on these poor septic systems. So the contamination just dissipates through whole communities and everybody is exposed, even if there are some people who do have better managed toilets. If their neighbours don't, they and their children are still going to be exposed to contamination.

And look, again, these communities are not the only communities that are prone to flooding, but often, because these are informal settlements, as we said, unplanned settlements, then they're on land that the government didn't necessarily want to build on, and other people don't want to live on. Particularly where we’re working, we have deliberately chosen to work in some of the most vulnerable communities in low lying, coastal, urban informal settlements that are prone to flooding, prone to effects of sea level rise. And prone to having poor drainage, so that even when there is just a heavy rain, let alone a severe, a more severe weather event, the communities are faced with water that doesn't drain away.

Alisha Wainwright 11:29

Thinking of these severe weather events, I’d like to share this perspective, also from Ibu Ina Rahlina. Here she tells us about the impact a flood can have on an informal settlement like hers.

Ibu Ina Rahlina 11:44

Yeah, it's a little difficult for the community when the flooding, because their usual activities will stop. Yeah, because they can’t go around, they can’t go from the outside, and also these vegetable and fruit sellers, who usually enter the settlement, do not sell as usual if there is a flood.

After the flood, residents usually get this skin disease like itching, burns and athlete’s foot, but some of them can go to the doctor to get medical care, but some of them, because their income is not enough to going to the doctor, they just - they're not doing nothing. But sometimes governments, from medical department, like going to the settlement to give some medicine, and sometimes volunteers give them medicine. So skin diseases like, it's usual for them.

Alisha Wainwright 12:50

When you hear about floods, you might think about property damage or immediate risk. But as Ibu Ina described – when it’s in an informal settlement with makeshift septic systems, you’re talking about serious sickness and a lasting danger to health. And that’s your focus at RISE, right?

Professor Karin Leder 13:08

So, the primary focus of RISE is to reduce exposure to faecal contamination that leads to gastrointestinal ill health. The commonest manifestation of gastrointestinal ill health is diarrhoea, but it extends beyond that. It often can lead to chronic inflammation in the gastrointestinal tracts, particularly of young children under five, who are most susceptible to being exposed to, to these kind of bugs. And the chronic inflammation means that they often don't absorb foods well. So not just, not just does it lead to acute episodes of diarrhoea, but it leads to chronic ill health, poor growth, stunting, malabsorption. And that in itself can lead to difficulties with schooling, and concentration, and other factors. And if you think about this in a way of, you know, multi-generational impacts, if the family is not able to afford, you know, a lot of highly nutritious foods in the first instance, you're then superimposing this kind of poor absorption –

Alisha Wainwright 13:40

Stacking it up?

Professor Karin Leder 13:42

Stacking it up. But there are other health problems. Another is that when you have poor drainage and pools of water in communities, you are often prone to mosquito breeding. And mosquitoes in these areas often carry diseases like dengue fever, being a common one. And then there's other common things when you live in crowded conditions - respiratory infections are more common because people - they often spread person to person, and we all learned through COVID that one of the things we need to do is to wash our hands more frequently, or sanitise our hands. Now, again, if you superimpose poor access to water services on a community that is kind of -

Alisha Wainwright 15:11

Yeah, if you don't have access to clean water, and you're telling someone - well, just wash your hands, that's not as easy for some people to do.

Professor Karin Leder 15:18

That's right.

Alisha Wainwright 15:19

Have informal settlements like Malinkiri always had these sorts of flooding and water systems issues? Or do you think these problems are getting worse because of climate change?

Karin Leder 15:30

Look, you're quite right, that it's always a problem. As I said previously, these communities are often built on land that other people don't want. And they don't want it for a reason. They’re often flood-prone lands, often low lying, often coastal, or at the bottom of a mountain, or, you know, built in a valley that's prone to getting flooded because of surrounds. So the topography, the geography of these informal settlement communities are not necessarily going to be resilient to rains and climate effects in the first instance. I think over time, a lot of the residents of community, in these communities have found ways to be much more resilient than I would be when I go and visit the communities. But things progressively are getting worse over time. And, if we don't do something about climate change, will continue to get worse. And the vulnerabilities that the people in these communities have to the shocks of climate change, their ability to be resilient to these climate shocks is becoming, you know, more and more tenuous because they're really already living at the extremes.

Alisha Wainwright 16:46

I’d like to pick up on that word - “resilient”. Because a lot of the time when we talk about these large-scale health problems, like flooding in informal settlements, it can feel very doom and gloom – the focus is on how vulnerable these communities are. But, as you said, there is a strength and resilience there as well.

Professor Karin Leder 17:07

Absolutely. We were in Indonesia about six weeks ago, when there was some flooding in Macassar. And we were hearing stories from another one of the field workers for RISE - she said to me that, exactly as Ibu Ina had said, that the communities are really close, but they also, you know, rely on sellers coming into the communities to buy - to sell fresh food. Come in on bicycles and motorbikes. And when there was no access, like on this day that I was there and there was flooding, the sellers don't come in. And I was asking her what happens, and she said - look, they get together and one neighbour says to the next, I've got some spare of X and maybe you've got some spare of Y. And they, they bind together, and they work together. Now, obviously, it is different in different communities. But you know, I hear about this and think about the fact I don't remember the last time I spoke to my neighbour. And, and we need to recognise that, these communities also, there's something really special and something unique about these communities, because of - perhaps because of their vulnerabilities in some ways, their strengths in other ways.

And what we are absolutely intent on in RISE is recognising that there are some things that these communities, the people who live in these communities would benefit from. Basic services that we are used to, the basic right to have your children not grow up with multiple episodes of diarrhoea, because they're exposed to pathogens, you know, poor growth, stunting, inability to get to school. We want to help people overcome these challenges.

Alisha Wainwright 18:55

Okay, so you’ve told us about the bigger picture goals of RISE, but can you tell us how you’re actually doing it?

Professor Karin Leder 19:05

Essentially, what RISE is, is what we call a randomised control trial, which is a way of developing the highest quality scientific evidence. A randomised control trial essentially always has an intervention that you give to some of the people and not to others. And then you look at differences in impacts and outcomes amongst those who got an intervention versus those who didn't.

The obvious things might be to say, well, let's ask about children's diarrhoea because you know, we're trying to reduce that. But when you have a study that's not blinded, where people know whether they've got an intervention, there is a problem in what's called responder bias - that the residents want to make us happy, you know, in a way, and they will - they might be prone to say, oh, no, we're fine. Because they, if they are happy with the intervention, and they're grateful for it, they’ll be less likely to report it. So we had to think of ways of being, I guess much more scientific and not prone to bias, and have outcomes that are much more objective. And the way that we're doing that is a little complex, but it's essentially, there's a few different things we're measuring. But the main one, or the easiest one to explain, is to look at the number of pathogens, the number of bugs that we're finding in the environment, and in the stools, the faeces of the children under five in those communities that have or have not received the intervention. Because our primary focus is on reducing exposure to faecal contamination.

And the intervention in some other studies might be a vaccine, or medication, or something. But here our intervention is really complex. Our intervention is an infrastructure build that is unique and site-specific to the needs of each and every community that we're working in. So it's not a one size fits all intervention. It’s an intervention co-designed with each community to address the major water and sanitation, and access issues that that specific community is facing.

Alisha Wainwright 21:21

So when we talk about infrastructure, just give me - like - a blanket list. What sort of things are you trying to add to the community?

Professor Karin Leder 21:29

As much as possible, RISE is trying to use what's called green infrastructure, or nature-based solutions as the way to approach in a holistic fashion, these water, sanitation, and flooding exposures, that these informal settlement communities are facing.

But essentially what it is - it's toilets, when needed, hand basins, connection of the toilets to what's called smart septic systems. So septic systems that are going to be properly managed and aren’t going to leach, to be leached out into the environment. Wetlands, which are ways of - it's using plants and soils to filter contaminated waste through often underground plant roots and soils, to clean out contaminants. And also, infrastructure that reduces people's exposure to flooding, either by providing better drainage systems, or by providing something like elevated walkways that gets people able to get into and out of their communities and their houses without having to wade through potentially muddy, flooded, contaminated paths that, as they're currently having to do.

Alisha Wainwright 22:44

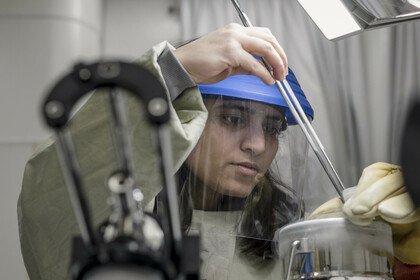

Let’s hear how the project is working. We spoke with Losalini Malumu who works in Kilikali settlement in Fiji. She’s the RISE Fiji engagement manager and part of her job is fostering a two-way relationship between RISE and the residents of informal settlements.

Losalini Mulumu 23:04

Sharing my experience with them helps build trust with the community members. Before, these communities, they already have, you know, other projects that came in, and they didn't follow through with what they had initially promised with the community members. So, me coming in there and informing them, hey, you're not the only one who, you know, is facing this issue. I've lived in informal settlements, so I understand what you guys are currently facing. And that helps them to build trust with community members and help them come to participate in the meetings or in the workshops that you always conducted in the communities.

Just seeing the changes in the community - when we first started engaging with them, there was not very much participation from the community that we have about only ten people that attend meetings. You know, once they start understanding the benefit that the RISE infrastructure will bring to the community, for their health and for their environment, now in our meeting, we have about 40 to almost about 80% attendance in those workshops. Once RISE completes the project they can take on the operation and maintenance of their system, because they start feeling that it's their system, and that's something that they need to take ownership of it. Which is very empowering.

Alisha Wainwright 24:39

Empowering. I find, you know, my family is from the Caribbean and my father's side is from Haiti. And oftentimes I hear of outreach programmes going in, doing something, and then leaving. And it's a very disempowering experience for the communities that remain, because it just, you see someone and you assume that they're just going to leave, and they don't really care about you. They almost care about what it is that they're doing. And I think what makes RISE, and similar organisations like RISE, stand out to me is the engagement of the community. I feel like that's the only way you really see lasting impact.

Professor Karin Leder 25:23

Absolutely. Right from the beginning of RISE, we have been very clear that we're not doing something to communities, we're doing something with communities. And that takes many forms. For, in terms of the infrastructure, we have been absolutely adamant that the infrastructure needs to be co-designed with communities, that they need to understand what we're trying to do, what the options for the infrastructure is, and then that communities need to get together and tell us what, where they want things built, how they want things built, what materials, etc.

Alisha Wainwright 26:01

The engagement, yeah.

Professor Karin Leder 26:02

Obviously, within you know, some limitations, but we - within the confines of what, you know what we are able to offer, but we are not coming in with, you know, a design, we are designing with communities. We've even had one instance where there was the beginnings of the building of a certain piece of infrastructure, and when the community saw it, they said, look, that's not going to work for us, you know. Now, there is obviously some limitations around that kind of flexibility, but we really are trying to work with communities so that if something that they see as a benefit, and as, as was just said, that they will take ownership of and look after, beyond the end of what is actually a scientific trial, and, and, you know, we will leave. The long-term success of infrastructure like ours needs to also have some expertise that we can’t expect these communities to have. And so, we are working with communities, both the informal settlement communities, but also, you know, the broader government communities.

Alisha Wainwright 27:17

I'm curious what kinds of expertise have local residents been able to bring to the RISE project?

Professor Karin Leder 27:24

Firstly, in each community, we have community representatives, who meet quite often and who talk across the twelve communities in each country, share experiences, share challenges, and the resilience factors as well. And each community will probably handle it in different ways. There are, in their demonstration site, the houses are taking it in turns to be responsible for various elements. In some communities, there are clear community links, often family links, for clusters of houses, and that cluster will be responsible for one element, or for some of the infrastructure that's near their household cluster. In others, it will be, you know, people who have particular interests, who might take over the management for the whole community. But again, it's up to the community to decide how, how it will work best for them.

Alisha Wainwright 28:20

What does success look like for RISE? Can you share that vision with me?

Professor Karin Leder 28:24

Our ultimate aim in this project is to create evidence to see whether this approach that we have to water and sanitation management does actually improve the lives of people who live in informal settlements, improve the health of their environment, and improve their physical health and wellbeing, in the ways that we anticipate it might. But we don't want to presume that it will, without studying that and garnering the empirical evidence. But if it does, then this may be a new approach to a holistic and sustainable way of managing water and sanitation. So it is potentially an approach that could be scaled up to help the currently 1 billion - in 25 years, there'll be 5 billion people - who live in these kind of informal settlement communities. It is likely to be one of a suite of solutions that might be available. it could be that we need, that this is, you know, version one, and that we find out because of climate impacts or other changes to the communities that our infrastructure needs to look a bit different in the future. But what we want is to try and get the evidence to improve not just the lives of the residents of the 24 communities that we're working in, but to have that be a blueprint for how this might be scaled up to improve the lives of billions of people.

And that is something that I feel is a real responsibility. And, and but as I say, also a privilege to be invited into the homes of some of the residents, when I do get a chance to visit. And hopefully, at the end of this, they will say - well, that was worthwhile.

Alisha Wainwright 30:25

Gosh, I really hope they do. And thank you so much, Karin, for speaking with me. The challenges these informal settlements face, with the floods and heavy rains – that all was an aspect of the climate crisis I didn’t really know much about.

And I'm not only illuminated by this conversation, but I'm also really inspired by your work, and the work your team is doing, and how it could help so many people on the planet. I really appreciate you for speaking with me today.

Professor Karin Leder 30:46

Thank you so much, Alisha.

Alisha Wainwright 31:06

Thanks for listening to this episode of When Science Finds a Way. And thanks to Professor Karin Leder, our contributors, Ibu Ina Rahlina, and Losalini Malumu, and their organisation RISE.

When Science Finds a Way is brought to you by Wellcome.

If you visit their website – wellcome.org – that’s Wellcome with two ‘L’s – you’ll find a whole host of information about research projects in informal settlements, as well as full transcripts of all our episodes.

Make sure to follow us in your podcast app, to get new episodes as soon as they come out.

And if you feel like you learned something important or interesting, or you just want to support the podcast, spread the word and share it with people you know.

Next time, we’ll be talking about human infection trials in Malawi. It may sound scary, but it’s a way to develop more effective vaccines, fast.

When Science Finds a Way is a Chalk and Blade production for Wellcome –a global charitable foundation that supports science to solve the urgent health issues facing everyone.

Show notes

Informal settlements are defined as residential areas that fall outside the jurisdiction of governments. These communities live without traditional centralised sanitation and water systems. As a result, the settlements are vulnerable to extreme weather events like floods, which cause wastewater to spread through homes and lead to serious health issues.

As climate change and nearby development increase the frequency and severity of floods in these settlements, organisations like RISE (Revitalising Informal Settlements and their Environments) are trying to help. In this episode, Alisha speaks to Professor Karin Leder, Head of Research at RISE, about projects in Indonesia and Fiji that are collaborating with local communities to combine scientific study with infrastructure building. They hear from Losalini Malumu and Ibu Ina Rahlina, RISE staff members and residents of informal settlements, who through their experiences demonstrate the critical role of collaborating with those most affected by these challenges.

Meet the guest

Next episode

Human infection studies are a quick and effective way to gather data to determine whether a vaccine is working. In the next episode, Alisha speaks with Dr Dingase Dula to learn more about the impact of infection studies in combating infectious disease.

Transcripts are available for all episodes.

More from When Science Finds a Way

When Science Finds a Way: Our podcast

Our podcast is back with a third season, uncovering more incredible stories of how scientists and communities are tackling the urgent health challenges of our time.