Chapter 1: Views on mental health and the role of science in understanding and addressing problems

This is the first chapter 1 of the Wellcome Global Monitor 2020: Mental Health

A central focus of this study is learning about the extent to which people believe science can help us understand and alleviate anxiety and depression. This chapter looks at the following questions to explore how people think and feel about science and mental health:

- Thinking about a person’s overall health, do you think mental health is more important, as important, or less important than physical health for a person’s wellbeing?

- In your opinion, how much do you think science can explain each of the following? A lot, some, not much, or not at all?

- In general, how much do you think science helps us treat the following health problems? Does it help a lot, some, not much, or not at all?

Worldwide, 92% of people said mental health is as important as physical health or more important than physical health for overall wellbeing.

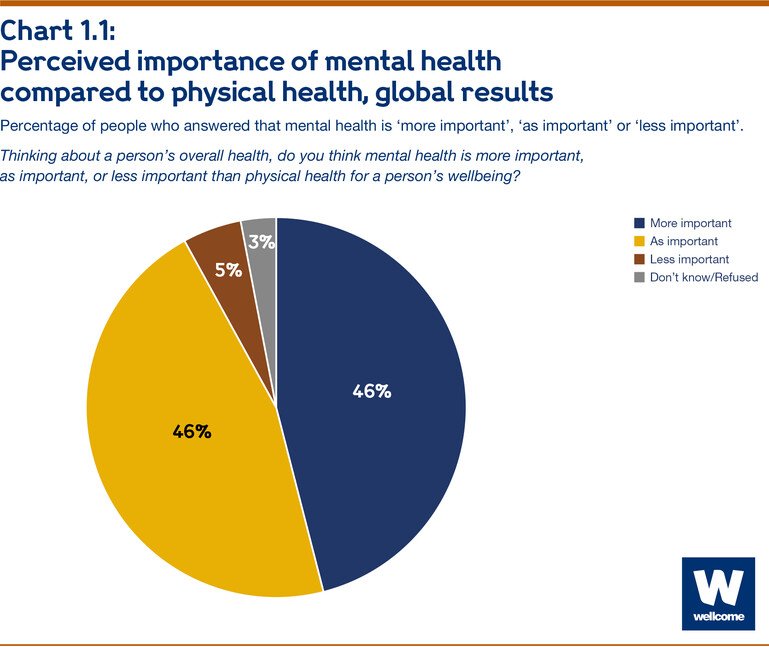

The study reveals a general consensus on the importance of mental health, as shown in Chart 1.1, with 46% of people worldwide saying it is just as important as physical health and another 46% ranking it as more important to overall wellbeing. Relatively few (5%) said mental health is less important than physical health.

Chart 1.1: Perceived importance of mental health compared to physical health, global results

Percentage of people who answered that mental health is ‘more important’, ‘as important’ or ‘less important’.

Thinking about a person’s overall health, do you think mental health is more important, as important, or less important than physical health for a person’s wellbeing?

People who have experienced anxiety or depression (defined as being ‘so anxious or depressed that you could not continue your regular daily activities as you normally would for two weeks or longer’ for this report) were more likely than those who have not to say mental health is more important than physical health – 53% compared with 44%.

Surprisingly, country income level had a greater effect on people’s views on this subject than their own lived experience of mental health issues. Overall, people in the world’s poorest regions were among the most likely to assign greater importance to mental health. This opinion was most prevalent in Sub-Saharan Africa, where 73% said mental health is more important than physical health. By contrast, less than a third of people in three high-income regions said mental health is more important: Western Europe (26%), Northern America (28%) and Australia/New Zealand (31%).

Most people in low-income countries said mental health is more important than physical health

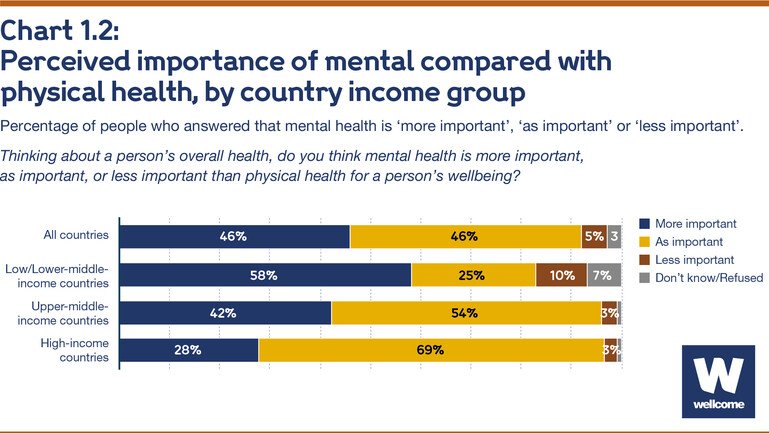

Chart 1.2 illustrates that in low- and lower-middle-income countries, most people (58%) view mental health as more important than physical health to a person’s overall wellbeing, whereas in high-income countries and areas, only 28% said mental health is more important. The results from upper-middle-income countries show that 42% of people place greater importance on mental health.

Fifty-eight per cent of people in low-income countries said mental health is more important than physical health to overall wellbeing, compared with 28% of people in high-income countries.

Chart 1.2: Perceived importance of mental compared with physical health, by country income group

Percentage of people who answered that mental health is ‘more important’, ‘as important’ or ‘less important’.

Thinking about a person’s overall health, do you think mental health is more important, as important, or less important than physical health for a person’s wellbeing?

Note: Due to rounding, percentages may sum to 100% ± 1%.

Perceived importance of mental compared with physical health (global demographic results)

Interact with the data in more detail via the chart below

Country-level results further demonstrate the strength of this relationship. Chart 1.3 plots the percentage of people who said mental health is more important than physical health against their country’s per capita GDP. Views of mental health as more important declined steadily as country income levels rose*, and people became more likely to put mental health and physical health on an equal footing.

Chart 1.3 also identifies outlier countries that do not follow this trend. For example, people in several Arab Gulf countries (Bahrain, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates) were more likely to prioritise mental health than their countries’ high-income levels would predict.

*R = 0.7. People were most likely to say mental health is more important than physical health in low-income countries like Ethiopia (88%) and Tanzania (84%) and least likely to do so in high-income countries like Sweden (16%) and Belgium (14%).

Views of mental health as more important than physical health declined as a country’s GDP rose.

Chart 1.3: Scatterplot exploring the relationship between the perceived importance of mental compared with physical health and country/area GDP

Percentage of people who answered that mental health is ‘more important’.

Thinking about a person’s overall health, do you think mental health is more important, as important, or less important than physical health for a person’s wellbeing?

Interact with the data in more detail via the chart below

Views on the importance of mental health also differed according to residents’ income within many countries.

Country-level differences were mirrored within many countries and areas, with low-income residents more likely than those with higher incomes to prioritise mental health over physical health. In Brazil, for example, 72% of those in the lowest 20% of the country’s income distribution said mental health is more important than physical health compared with 43% of those in the highest 20%. In the US, people in the lowest income group were more than twice as likely as those in the highest group to say mental health is more important than physical health – 45% compared with 19%, respectively (see the Methodology report for more detail).

While many people prioritise mental health over physical health, fewer think science can explain emotions or that science can have as much impact on the mental aspects of health and wellbeing as on the physical aspects.

Less than one-third of people worldwide think science can do ‘a lot’ to explain emotions or treat anxiety or depression.

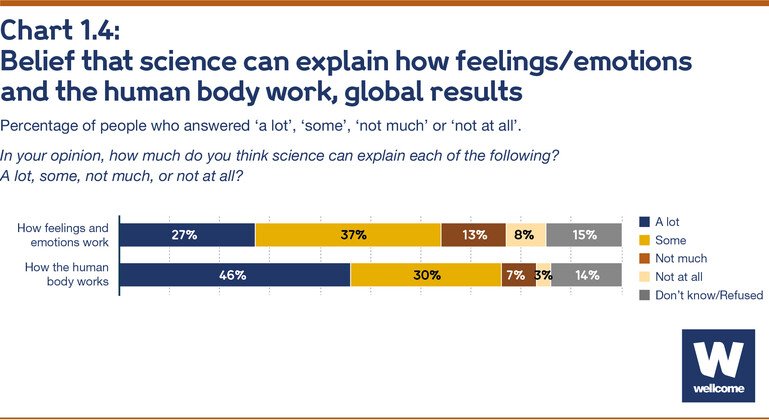

Chart 1.4 shows that while 46% of people worldwide said science can explain a lot about how the human body works, only 27% said the same about science’s ability to explain feelings and emotions. Views on mental and physical health become more similar, however, when broadened to include the opinion that science can explain at least ‘some’ of how feelings and emotions work, with 64% having this view globally compared to 76% saying the same about the ability of science to explain the human body.

Chart 1.4: Belief that science can explain how feelings/emotions and the human body work, global results

Percentage of people who answered ‘a lot’, ‘some’, ‘not much’ or ‘not at all’.

In your opinion, how much do you think science can explain each of the following? A lot, some, not much, or not at all?

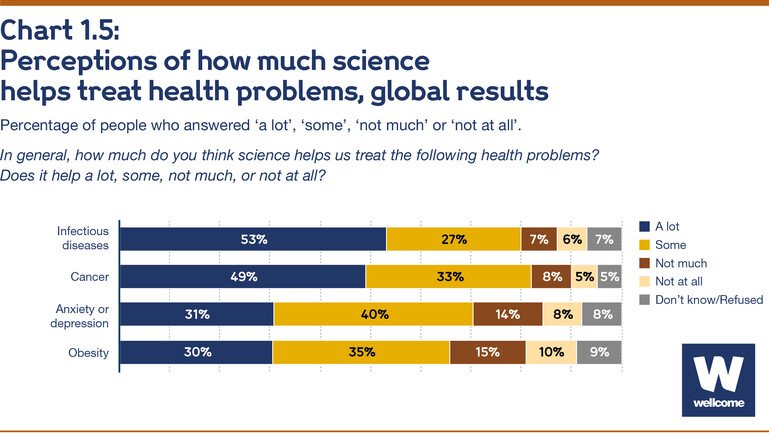

Chart 1.5 reveals that about three in 10 people worldwide (31%) said science does a lot to help treat anxiety and depression, which is similar to the percentage of people who believe that science is able to explain a lot about feelings and emotions. People were more likely to believe science can do a lot to help treat infectious diseases (53%) and cancer (49%).

Chart 1.5: Perceptions of how much science helps treat health problems, global results

Percentage of people who answered ‘a lot’, ‘some’, ‘not much’ or ‘not at all’.

In general, how much do you think science helps us treat the following health problems? Does it help a lot, some, not much, or not at all?

These figures varied somewhat across global regions and demographic groups, but in virtually all groups, people were more likely to say science helps treat infectious diseases and cancer than to say it helps treat anxiety and depression.

However, the perception that science can be at least somewhat helpful in addressing mental health issues was broadly held across countries and among individuals in different groups within countries, and there was remarkably little variation by age, demographic status or geography.