What treatments are working for Covid-19?

From existing antivirals to new antibody therapies – researchers are working tirelessly to find the best drugs to treat Covid-19.

Ginebra Pena / Getty Images

So far, apart from clinical care and oxygen, only a few drugs have proved effective at treating patients with Covid-19: the anti-inflammatories dexamethasone and tocilizumab, and a combination of monoclonal antibodies (casirivimab and imdevimab); but the latter only works in patients who haven’t mounted an immune response to the virus themselves.

The search for safe and effective treatments must continue. Even though vaccination is underway and more than 2.5 billion vaccine doses have been given so far – mostly in high-income countries – Covid-19 continues to spread across the globe.

Teams of scientists are looking into more than 300 potential treatment options, running thousands of studies around the world.

What are the main approaches for Covid-19 treatments?

Oxygen

Oxygen is one of the essential medicines for treating patients with Covid-19. As the SARS-CoV-2 virus attacks the lungs, it can cause pneumonia and hypoxaemia (a lack of oxygen in the blood). So for people hospitalised with Covid-19, oxygen therapy is lifesaving.

But low- and middle-income countries face hurdles in getting oxygen to patients – it’s expensive, the equipment is not designed for use in low-resource settings, and the countries lack the infrastructure needed, such as electricity and transport networks.

Wellcome is co-leading the Covid-19 Oxygen Emergency Taskforce with Unitaid to facilitate access to emergency oxygen in low- and middle-income countries.

As well as making oxygen available where it’s needed, more treatment options are essential for treating people with Covid-19 everywhere. Researchers are taking a wide range of approaches to find effective and safe drugs.

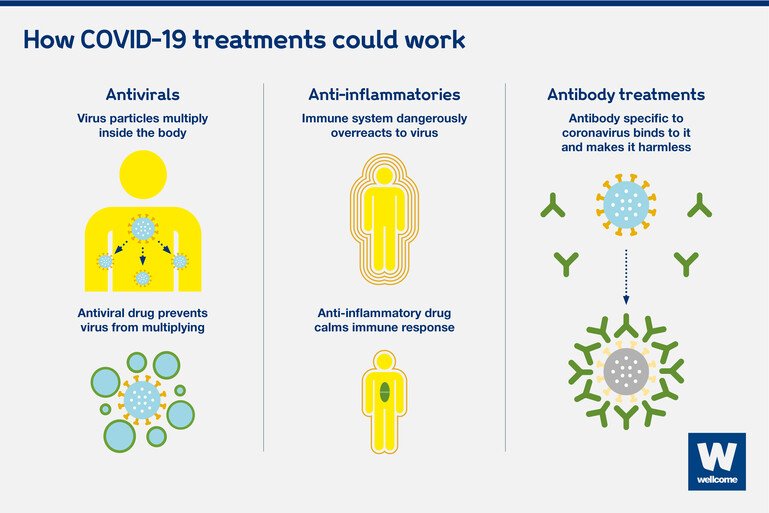

The three main approaches are: antivirals, anti-inflammatory drugs and antibody treatments.

Antivirals

Antiviral drugs work by preventing a virus from developing inside the human body.

Every virus is different and attacks cells in specific ways, and the antiviral drugs that fight them off are specific too. Very rarely does an antiviral built for one virus also work for another. But it can happen: for example, some HIV drugs have also proved effective in fighting off hepatitis B.

While several antivirals specific to Covid-19 are in clinical trials, finding one that works will take time. In the meantime, researchers are hopeful that some existing antivirals, whether already on the market or experimental, could have some useful effect against SARS-CoV-2.

One such antiviral, molnupiravir, has been found to cut hospitalisations and deaths by half, if taken early after symptoms develop. While most Covid-19 vaccines target the spike protein on the outside of the virus, molnupiravir works by targeting an enzyme the virus uses to make copies of itself. If authorised by regulators, molnupiravir would be the first oral antiviral medication for Covid-19.

Other existing antivirals have been tested, but so far have not proved to be effective against Covid-19. Examples include:

- Remdesivir, an antiviral tested as an Ebola treatment. Although it has been authorised for emergency use in some countries, the WHO Solidarity Trial showed that remdesivir does not reduce the risk of dying of Covid-19 or the length of time patients need to stay in hospital.

- Hydroxychloroquine, a drug used to treat malaria and rheumatology conditions. After receiving high-profile attention in the media, the large-scale RECOVERY Trial showed that hydroxychloroquine has no benefit for hospitalised patients with Covid-19.

- Lopinavir-ritonavir, a combination of antivirals used to treat HIV. The RECOVERY Trial showed it had no clinical benefit for Covid-19 patients.

These results were disappointing, but it's really important to know them, so researchers and clinicians can look at other potential treatments.

Another drug that has been gaining visibility for its potential to treat Covid-19 is ivermectin – not an antiviral, but an anti-parasitic drug used to treat diseases caused by parasitic worms. The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends that ivermectin should not be used to treat Covid-19 outside of clinical trials because there isn’t enough evidence about its benefits. One such trial is Oxford's PRINCIPLE trial in the UK, which is looking to see if the drug helps people over-50 with Covid-19 symptoms.

Wellcome

Anti-inflammatories

Anti-inflammatory drugs work by calming the immune system. In people with severe Covid-19, the body’s violent reaction in trying to fight off the virus can cause serious harm and even death. Anti-inflammatories can reduce this response.

Researchers have found both positive and negative results. They have looked at:

- Dexamethasone, a type of steroid used to reduce inflammation in a range of conditions, including sore throats. This was the first drug to be shown to be effective in reducing death rates – by up to one third in hospitalised patients with severe respiratory complications of Covid-19, according to the RECOVERY Trial.

- Tocilizumab, an intravenous drug used to treat rheumatoid arthritis. The RECOVERY Trial showed it reduces the risk of death when given to hospitalised patients with severe Covid-19, and it shortens the time they spend in the hospital.

- Interferon beta-1a, used to treat multiple sclerosis by stopping the immune system from damaging the coatings of nerve cells. Interferons have previously been found to show some effects against MERS-CoV and SARS, which are also caused by coronaviruses, but the WHO Solidarity Trial showed that it had little or no effect on Covid-19 patients.

Antibody treatments

Antibodies attack the virus directly. Unlike antivirals and anti-inflammatory drugs, antibodies are produced naturally by people who have had an infection and recovered. When given to patients who are fighting off an infection, antibodies can boost their immune response and stop the virus from causing further harm.

There are two ways that antibodies can be used:

- Convalescent plasma can be extracted from the blood of Covid-19 survivors and injected into patients who are fighting the disease. This was widely used as a treatment around the world at the start of the pandemic, but the RECOVERY Trial found no convincing evidence of its effect.

- Monoclonal antibodies are antibodies specific to Covid-19. While they also originate in the blood of people who have recovered, that is only the starting point. Scientists select the relevant antibodies, extract and expand them, and then manufacture them in large quantities. A combination of monoclonal antibodies produced by Regeneron (casirivimab and imdevimab) is the first therapy specific to Covid-19 that was proved to reduce deaths – but only in hospitalised patients who haven’t mounted a natural antibody response of their own, as the RECOVERY trial showed. However, monoclonal antibodies are typically very expensive and not widely available across the world. Covid-19 could be the catalyst to change that, so these treatments become more affordable and accessible to people in rich and poor countries alike.

Antidepressants

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRI)

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are a widely used type of antidepressant. Mainly prescribed to treat depression, particularly persistent or severe cases, many antidepressants have been found to have anti-inflammatory properties. There are ongoing studies to find if any SSRI’s could be used as potential treatments for Covid-19.

The results of a new randomised clinical trial have indicated that using fluvoxamine to treat high-risk outpatients with early-diagnosed Covid-19 reduced the need for prolonged observation in an emergency setting or hospitalisation, compared to a control group who received a placebo. While this shows promise, more research and clinical trial data is needed on SSRIs as a Covid-19 treatment.

How do we find out whether treatments work?

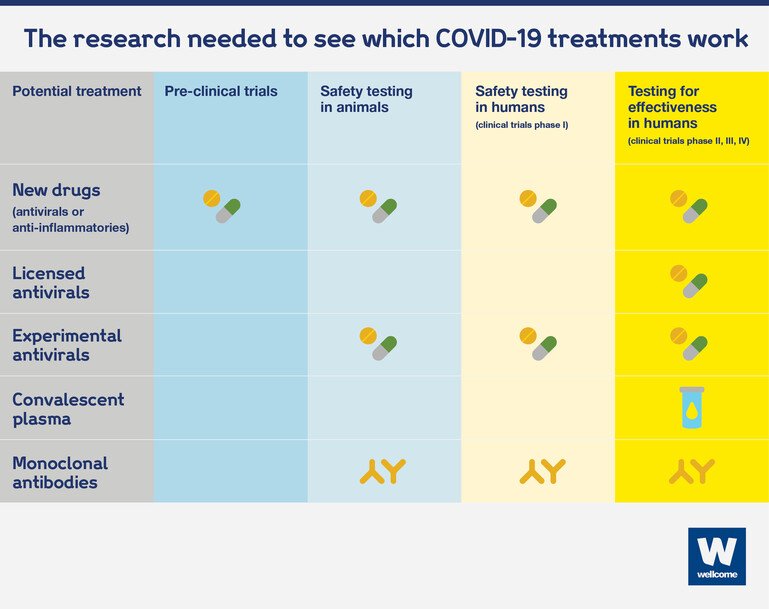

Potential new drugs usually have to go through years of laboratory work, animal testing and human clinical trials before they’re proved to be safe and effective against a specific disease.

This is why researchers have first been looking into existing drugs, some experimental and some already licensed, that were developed for other infections, such as Ebola and malaria. These drugs have a head start and we can establish more quickly whether they are useful against Covid-19.

Experimental drugs, such as remdesivir, may have already been tested in animals for safety. But they usually have to go through safety trials in humans, to assess what the safe dose is, before moving into clinical trials to assess how effective they are.

Existing antivirals have already been proved to be safe for humans, at a specific dose, so what needs to be done next is test whether they work in people with Covid-19. Only large randomised controlled trials, with hundreds or thousands of people enrolled across the world, can tell us whether existing antivirals bring benefits to people with Covid-19.

Wellcome

Existing anti-inflammatory drugs are also already known to be safe if used in certain ways. But because of the way these drugs interact with the immune system, we need more data to understand whether they are safe in the context of a Covid-19 infection. This can be done through small studies first, to assess what the right dose is, before moving into large randomised controlled studies to test their effectiveness.

Monoclonal antibodies are a new potential treatment, so they also have to go through safety trials in humans. But because these are natural antibodies originating in human bodies, not synthetic compounds, safety trials will take less time to conduct. After that, effectiveness studies can get going.

Large randomised clinical trials – such as the WHO's Solidarity clinical trial and the UK’s RECOVERY Trial – are essential for getting robust data about which treatments work against Covid-19. These studies are designed to be adaptable ongoing platforms, so they can quickly stop testing drugs that prove not to be working, and add new ones as they develop.

Pressing play on the video above will set a third-party cookie. Please read our cookie policy for more information.

The nature of of Covid-19 is that we need drugs. We need drugs which we know work and we need them as soon as possible.

Covid-19 treatments: inside the world's largest clinical trial for Covid-19

Professor Martin Landray, Nuffield Department of Population Health, University of Oxford: "For patients that are admitted to hospital with Covid-19, then typically, one in five will sadly die, so actually saving lives is the key thing we're looking for.

The Recovery Trial was set up at record speed. It had to be, we know it had to be. We had to set this trial up within two weeks. Well, we beat that and we set it up within nine days. That is a speed and scale that has never been matched in any setting, let alone in the context of a pandemic.

We're studying four or five drugs simultaneously. And as we get enough evidence that one drug is definitely useful, or perhaps not so useful, we can stop studying that drug and move on and slot in other drugs as they become available.

To date, there are just over 10,000 patients who've enrolled in the clinical trial.

Roughly speaking, that's about 13 or 14% of all patients who've been admitted to hospital within the UK, which I think in itself is something of a record.

I mean, the collaboration has been colossal from different parts of the system. From within the UK, the Department of Health, from the regulatory agency, the MHRA, from the ethics committee, from the research infrastructure on the ground, coordinated from the team at University of Oxford.

But this is not about any one person or organisation. This is about teamwork and that's what matters."

We must continue to fund large-scale trials across the world to find treatments for Covid-19.

How do we make Covid-19 treatments accessible to all?

Covid-19 has reached every corner of the world, and it will keep spreading unless it is controlled everywhere. To stop the pandemic, to get societies back to normal, and to get economies moving again, any treatments and vaccines must be made accessible to everyone who needs them, everywhere in the world, regardless of their ability to pay.

For that to happen:

-

governments, industry and philanthropy must pool resources to pay for the risk, the research, manufacturing and distribution to ensure everyone has access to treatments

-

clinical trials need to take place across the world, to make sure treatments work for everyone

-

national governments must work together to ensure that coronavirus treatments can be manufactured in as many countries as possible and distributed globally to everyone who needs them.

Global collaboration is paramount for ensuring global access to treatments. To promote this, the ACT-Accelerator was launched.

Through this collaboration, the World Health Organization, governments and international health bodies have pledged to make sure that any tools developed to fight the current pandemic – vaccines, diagnostics and treatments – will be distributed equitably to everyone who needs them. But more funding is needed to make the work of the ACT-Accelerator possible.

This explainer was originally published in May 2020.