More people should have access to monoclonal antibodies. Covid-19 can make that happen

Monoclonal antibodies, one of the most promising treatments for Covid-19, are usually expensive and not available worldwide. Lindsay Keir highlights what needs to be done to change that.

Benson Ibeabuchi/AFP via Getty Images

Everyone, from researchers, clinicians and policy makers, to the president of the United States, seems to be talking about monoclonal antibodies and their potential to treat Covid-19. The big question for me is: if we find one that works, how can we make sure that people around the world benefit from it?

These innovative medicines have transformed the way we treat a range of diseases, including many types of cancer. They are also being developed for several infections and neglected tropical diseases like HIV and snakebites – and now for Covid-19.

It’s exciting that, months since the pandemic started, more than 70 monoclonal antibodies targeting SARS-CoV-2 are in development. The hope is that these treatments will reduce the severity of the illness, or even prevent people catching Covid-19. Several studies are underway, with early results from Elly Lilly and Regeneron showing encouraging signs.

However, as exciting as this research is, I’m concerned that these treatments – if they’re proven to be effective – will be very expensive and only rich people and wealthy countries could afford them.

If we don’t act now, we run the risk of Covid-19 treatments only benefiting the affluent in high-income countries. But if we do act, millions of people around the world could benefit from monoclonal antibodies – not only for Covid-19, but for many other diseases too.

There is global need, but not global access

When I worked as a doctor in the intensive care unit, I saw first-hand the potential of monoclonal antibodies to save the lives of young children.

Bronchiolitis, a disease caused by the RSV (respiratory syncytial) virus, can be mild for many children under 5, but is a scourge on vulnerable pre-term babies. It can cause severe breathing difficulties which require oxygen treatment. In the UK, for more than 20 years we have been giving at-risk babies a monoclonal antibody called palivizumab (Synagis) during the RSV season. The drug protects them from getting the disease and has been shown to reduce hospitalisations by 80%. However, more than 100,000 children still die every year because of RSV – 99% of them are in low- and middle-income countries, where this treatment is either not available (because it hasn’t been licensed), or not affordable.

Cost is an issue for most monoclonal antibodies. They are some of the most expensive drugs in the world. The average treatment in the US can cost between $15,000 and $200,000 per year.

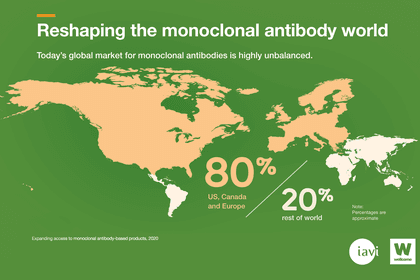

The cost is influenced by many things including the target market, and currently most of these drugs are made for high-income countries. In fact, around 80% of monoclonal antibodies sales are in the US, Canada and Europe.

Cost isn’t the only barrier. Monoclonal antibodies are also not widely available.

Despite some of these medicines being around for 30 years, few are licensed in low- and middle-income countries. Partly, that’s because registering antibody drugs isn’t always straightforward in these countries, which puts off some manufacturers.

Another reason is that both the market and manufacturing capacity are overwhelmingly concentrated in rich countries. Monoclonal antibodies are mostly developed for use in health systems that have the means to store them at cold temperatures and give them to patients through intravenous infusion, which can take hours and needs staff to monitor. That’s not feasible in most hospitals in low- and middle-income countries.

And when monoclonal antibodies are licensed in low-resource nations, often they are not available through public health systems – making them unaffordable to most people, who have to pay for them out of their own pockets.

All this leads to 85% of the world’s population unable to access these lifesaving medicines.

Covid-19 must be the catalyst to make treatments accessible

There are many things we can do to change the status quo and make monoclonal antibodies more accessible – our recent report with IAVI, the International AIDS Vaccine Initiative, captures some of these.

One is investing in innovative technologies that can help reduce development and manufacturing costs and make these drugs cheaper. India has established itself as a hub for manufacturing low-cost versions of registered antibodies, with around 100 such companies.

These companies are now turning their attention to novel monoclonal antibodies for local diseases. And they have the technology to make products that are suitable for local healthcare systems – drugs that can be stable at higher temperatures and can be given to patients more easily. They have also shown cost reduction is possible – a good example is the rabies monoclonal antibody from the Serum Institute of India which costs $20 a dose.

The Covid-19 pandemic gives us a major opportunity to apply these innovations and develop a pathway to make monoclonal antibodies globally accessible.

We must prioritise research into treatments that can be delivered easily in all healthcare environments. When Covid-19 monoclonal antibodies are shown to be safe and effective, it is crucial that we reserve manufacturing capacity for low- and middle-income countries, develop a clear allocation framework, and support developers to think about global access. We also need to seek quick regulatory approval of these products in more countries.

It will take effort and collaboration, but one of the most inspiring things about this crisis is how different industries and groups are pulling together. Initiatives like the ACT-Accelerator and the Covid-19 Therapeutics Accelerator are already working on some of these issues. But there's more we can do to support and build on them to make sure effective treatments are accessible to all.

To get these conversations started, we’ll be organising a series of virtual meetings to discuss the recommendations we published, add to them and collectively agree to act.