How research has fundamentally changed the response to Ebola in DRC

It's a year since the Ebola outbreak in the Democratic Republic of the Congo began and research has been essential in saving lives. But as Josie Golding explains, if we want to prevent future outbreaks lasting a year, the world needs to address research gaps.

We have never seen an Ebola outbreak in a highly political and war-afflicted area before. This region of DRC is often served by poor or non-existent roads and limited electricity, and where health professionals are being targeted by violent groups.

But this outbreak has also seen a fundamental change to how we deal with Ebola, which has a fatality rate of 67% if left untreated.

For the first time in the history of this deadly disease, we have been able to deploy a vaccine that protects against Ebola, something that Wellcome has supported during this outbreak. This vaccine, produced by Merck, can only be used during a clinical trial. As such, each person receiving the vaccine must understand that this is an experimental vaccine, and agree to follow-up checks after receiving it.

But we are researching other solutions too. Vaccines are great at preventing disease, but what happens when someone has been infected?

Back in November a randomised clinical trial began looking at four different treatment options for Ebola – an antibody cocktail ZMapp, a monoclonal antibody mAb114, a monoclonal antibody cocktail REGN-EB3 and an antiviral known as remdesivir.

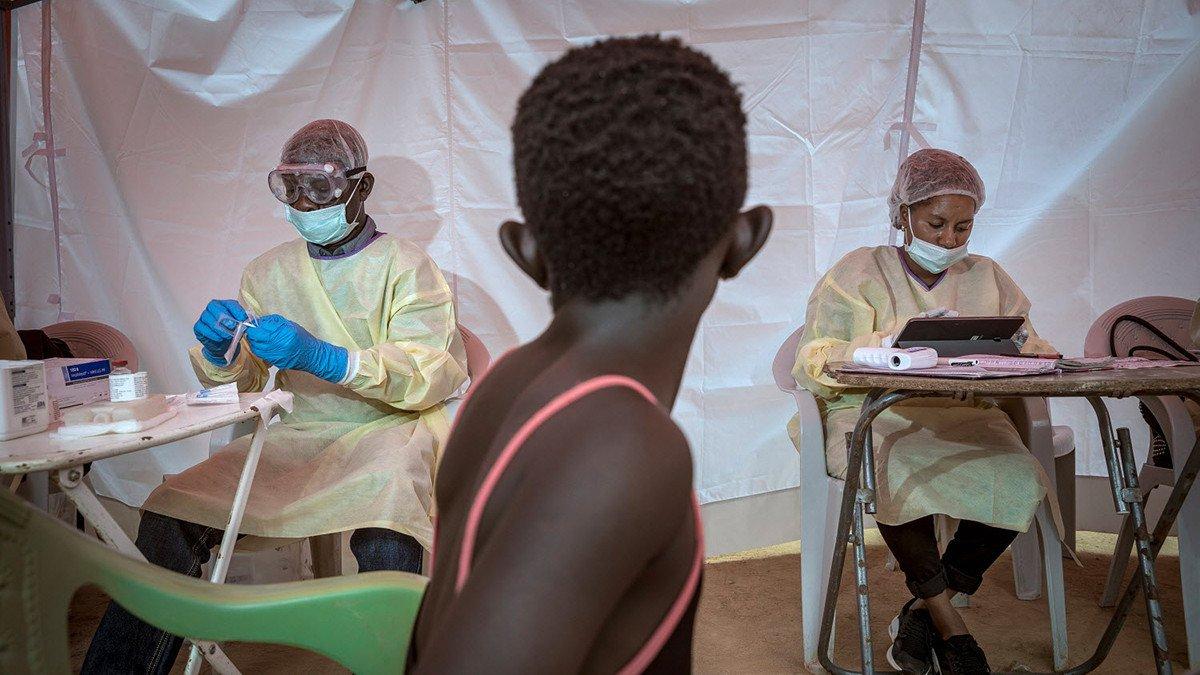

An infected person is randomly allocated a therapeutic in a health facility and carefully monitored to see if there are any improvements to their health. The results of this trial could tell us whether there is an ideal drug to give to those sick with Ebola.

Carrying out research during an outbreak is not easy and requires a huge commitment and support from all those involved, most importantly from the communities affected by the outbreak. It requires people to be trained to carry out research. Of course, long-term investment in countries at risk from epidemic-prone diseases is needed – and research needs to be considered alongside this. If we want to prevent or deal with outbreaks better, we must commit to how we do this.

Later this year, the WHO will publish an R&D Blueprint roadmap that will outline the gaps remaining for vaccines, therapeutics and diagnostics against Lassa fever, and the Ebola, Marburg and Nipah viruses. This will include additional and complementary vaccines that could be made available for Ebola (something that was also highlighted in May 2019 by the WHO Strategic Advisory group on immunisation).

We must use this as a launch point to properly address the research gaps and work together to prevent outbreaks like the DRC Ebola outbreak from reaching a one year mark at all.