With better global data we can outsmart drug-resistant infections

The impact of drug-resistant infections is much higher than previously thought, a new report from the Centers for Disease Control shows. To stop the rise of these infections, we need reliable global data.

Every 11 seconds someone in the United States gets a drug-resistant infection. Every 15 minutes a person dies.

These are the headline stats in a new report from the US CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention).

New data shows there are 2.8 million infections and 35,000 deaths in the US every year as a result of drug-resistant infections. This means impact is much greater – double the death rate, in fact – than previously reported six years ago.

While this report gives the picture in the US, the rapid rise of infections that are resistant to currently available treatments has global resonance.

It is not simply that our current understanding of the burden of infections due to antimicrobial resistance is likely to be poorly estimated. We must see this report as a clarion call for getting better global data on drug-resistant infections and their burden.

For the first time, the CDC were able to provide a more accurate picture of this health threat using data on patients from electronic health records.

Having accurate and up-to-date information has enabled the CDC to be vigilant – to introduce effective prevention measures which are reducing infections and deaths in the community and in hospitals. The report shows that, since 2013, prevention efforts have reduced deaths from antibiotic-resistant infections by 18 percent overall, and by nearly 30 percent in hospitals. The CDC also have a detailed picture of which bacteria are posing the most urgent threats to communities in the country.

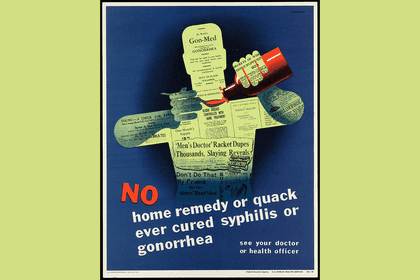

In global conversations on how to successfully stop the rise and spread of drug-resistant infections the spotlight often falls on the need for new treatments. Absolutely we need new antibiotics to replace those no longer working so doctors can treat patients and save lives. And absolutely we need government and industry to step up to fix the failed market for antibiotics.

But reliable data is central to successfully addressing the rise in resistant infections, enabling policy makers and healthcare providers to implement national action plans and allocate resources efficiently at local, national and global levels.

Good data starts with appropriate sampling from patients with a suspected infectious disease which can then be tested and reported to improve individual patient management and local prescribing policies. This data can then be collected to inform national surveillance, to establish evidence-based guidelines and create programmes of infection prevention and enable resource planning. Yet this description of the generation, dissemination and analysis of data from a patient through a system is far from reality in many countries.

Many low- and middle-income countries do not have the laboratory and analytical capacity or lab management infrastructure they need for action. In many settings patients are not always sampled when they present with an infection. Most existing surveillance systems are based on laboratory results alone, lacking the patient-level data essential to understand the burden and impact of drug-resistant infections on patients. Without robust patient-level data, governments cannot create effective interventions.

Better national data is also needed to inform global surveillance initiatives, to track resistance over time, signal where and when interventions are needed and identify which countries require support to build capacity. For this we must address the current fragmentation of systems and develop international standards and tools for collecting, analysing and sharing data.

With World Antibiotic Awareness Week upon us (18-24 November) we should be in no doubt that the rapid spread of these dangerous infections is happening now and is causing problems for doctors and patients every day and in every country.

Supporting countries to develop and use integrated patient and laboratory-based surveillance systems in a way that is appropriate for their needs and context is vital if we are to protect patients and the medical treatments and procedures we rely on to save and improve lives.