Episode 11: Should we give out cash to improve mental health?

Alisha speaks to Professor Vikram Patel to explore how cash transfers could hold the key to coming up with a universally applicable and low-cost breakthrough in the treatment of mental health disorders.

Listen to this episode

(Music starts)

CLIP FROM VIKRAM 0:04

“The need to do more research cannot be the excuse not to act now on what we already know - and I’ll tell you what, we know enough about cash transfers to act now, and that is what I think needs to be done most urgently”

Alisha Wainwright 00:23

This is When Science Finds a Way - a podcast from Wellcome about the science that’s changing the world.

I’m Alisha Wainwright.

And on this series, I’m talking to the global experts who are actually making a difference, as well as the people who have inspired and contributed to their work.

On this episode…we’re going to hear about a revolutionary idea in the field of global mental health that has the potential to change millions of lives.

We’re not talking about new medications, or experimental treatments or technologies. It’s far simpler than that. It’s giving people cash. Money. Mulah. Dinero.

Because, as we’re about to hear, poverty and mental health go hand in hand. So, why not give people money to help break up that cycle?

CLIP FROM VIKRAM 01:18

“There’s a lot more coming out of this amazing programme of research but all of it is pointing to proof that giving money to poor people in fact not only promotes your Mental Health but prevents premature mortality due to Mental Health problems.”

Alisha Wainwright

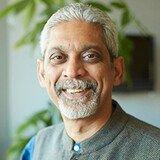

Professor Vikram Patel is a psychiatrist, who’s committed his career to understanding how factors like poverty can influence mental health, and how we can better support those affected. He’s now a global leader in his field, working as Professor of Global Health at Harvard medical school, Co-founder of numerous global mental health initiatives, and the recipient of so many awards and accolades that listing them would take up this whole episode… so it’s no surprise that in 2015 he was named in Time Magazine as one of the world’s most influential people.

In short, he’s a big deal, and he should be intimidating right?

Turns out, that is not the case.

Vikram walked me through how poverty and mental health are connected, and why cash transfers have to be part of the solution…

(Music ends)

Vikram Patel 02:30

So the relationship between poverty and mental health has been a contentious one for a very long time. And particularly in the context of global health. It was widely thought that mental health problems, particularly mood and anxiety problems, were problems of the affluent, the worried well, that actually poor people had more important things, as it were to be concerned about than their mental health. So a lot of my early research really explored is that, in fact, true. Is it in fact, the case that people who live in conditions of poverty, in fact, do not experience mental health problems? And what we found - and this has been replicated time and again, in every single study I know from the Global South, there is a strong relationship between living in poverty and there's a variety of different indicators of poverty, like low income, for example, or low education levels, and a higher risk of depression and anxiety, both a higher risk of suffering from one of these conditions but also a higher risk of a worse outcome in terms of how chronic these problems are. And indeed, the overall social and economic consequences of those problems. Is the relationship bi-directional? It absolutely is.

Alisha Wainwright 03:43

So just walk me through that - how is it bi-directional?

Vikram Patel 03:46

So let's first think of the direction through which poverty might cause mental health problems or lead to poor mental health. There are many different pathways through which this can happen. But the ones that I think are most relevant from a population perspective are firstly adversities in childhood. We know that adverse childhood experiences are perhaps the single most well demonstrated, well replicated risk factor for poor mental health. And interestingly enough, it seems to be the case for almost every type of mental health problem.

Alisha Wainwright

Wow.

Vikram Patel

And adversities in childhood are strongly associated with growing up in poverty. The most common kinds of adversities, of course, are simply child neglect. But there are other kinds of adversities, environmental adversities. Which are, which are also are more common if you grew up in poverty. The second important aspect of living in poverty is uncertainty. It really reflects, for example, in the experience of a parent who's unable to be sure whether they'll be able to bring food on the table for their family tomorrow. And if you try and imagine how that uncertainty when it's happening day after day, after day, month, after month, after month, with no real sign of when it's going to end, you can quickly imagine how that can wear your brain down, wear your mind down and create the substance for the worst risk of poor mental health. So how does living with poor mental health lead towards social and economic outcomes or, you know, use the word poverty as an umbrella term? The most obvious ways are through impairing your ability to be successful in your education. And we all know that education is a very important predictor of lifelong economic success. But if you are struck with a mental health problem, when you're working, equally, you will find that your productivity at work is going to suffer and the risks that you might lose your job are much higher. So that is one very important pathway. A second important pathway is through health care costs. Because most people with mental health problems around the world are unable to access good quality public health care. They are usually shopping for, you know, all kinds of cures and they spend a tonne of money.

Alisha Wainwright 06:00

Well we’ve been talking about this with Leonidas Valverde da Silva, who lives in São Paulo. He’s now in his thirties, and studying for a PHD focused on the link between poverty, identity and mental health. His studies have been inspired by his own journey… He explained to us - through a translator - how growing up in poverty led him to experience problems with his mental health…

Leonidas Valverde De Silva 06:26

(Portuguese fading to voiceover)

So Leonidas grew up in Sao Paulo, on the periphery, outside in a neighbourhood called Santo Amaro. It was a one room house, eight square metres for the kitchen, the living room for everything together. There was yeah, really limited resources. So they didn't have any water, they would share one piece of bread between everybody or the milk between everybody, the bathroom situation was very complicated. And Leonidas was the oldest of seven kids. So then became also really responsible for all the other kids. It was a very poor neighbourhood. But then the neighbourhood also began to develop. And with this growth and development, there was really this also increase in violence, increasing crime. There was the violence in the community, but also domestic violence. His father had problems with alcohol. He really experienced a lot of confrontation with violence, which really led also to then a lot of feelings of anxiety.

He always felt that he was kind of an anxious person, even an anxious kid as long as he can remember. But this feeling really grew. I mean, he was exposed to shootings and to guns that were so common and became really sensitised to this violence that was so commonplace. He remembers just this very strong feeling of fear. And that's the thing that he feels marks him most and was the biggest marker in terms of what influenced his mental health, this exposure to violence. As he started to get older, especially in adolescence, things started to get worse. When he was 18, he had his first panic attack, which manifested really like a seizure. He was taken to the hospital. He had then repeated panic attacks. And the doctor said it was just exhaustion and burnout. His dad was also very authoritarian, and machismo and had a lot of prejudice especially about mental health. Mental Health was seen through a really different lens and more of a religious lens and symptoms of mental health would be seen as more related to demons.

Alisha Wainwright 08:38

Wow, what is your take on that Vikram?

Vikram Patel 08:40

Well, I think you know, what we've just heard is a very poignant personal story that really describes from the personal narrative how living in poverty leads to poor mental health. This is unfortunately, not the lived reality only of the person we just heard, but in fact, the lived reality of billions of people around the world who live in these kinds of conditions. I call it the vicious cycle of poverty and poor mental health. And you know, Alicia, I think this is important because for so long people have ignored this association between disadvantage and mental health from the global context. Remember that a lot of global development assistance and prioritisation of health problems is always focused on diseases that disproportionately affect the poor. But for a lot of these folks who are making these important policy decisions, they would not really think of mental health problems as legitimate investments to make, they will think of, you know, TB and HIV, for example, because these problems, of course, also affect the poor disproportionately.

Alisha Wainwright 09:42

It’s also linear too right? Like, you can give a pill or a vaccine or something that's almost like very simple to solve that problem. What you're discussing, and what we'll get into down the line of the ways to sort of mitigate this, it's a little bit more complex than perhaps giving a shot in the arm.

Vikram Patel 10:00

I think, Alicia, you really hit the nail on the head. There is a real attraction of these simple technical solutions in the global health and development world. And that's been right from the beginning. And you know, you pointed out vaccines, people love the idea of a shot that will help cure or prevent some kind of medical problem. They shy away from complex issues that involve an interaction between the social, the political, and biomedical, because that seems to be too complex for the kinds of solutions that you know, many of the global health and development leaders really prefer.

Alisha Wainwright 10:39

So we know poverty is linked to poor mental health, then it seems like the best way to alleviate that is to just give people money, right? So cash transfers? And this isn't new - governments and NGOs around the world have been giving cash transfers for various reasons for decades. Can you talk a little bit about that history and about the benefits of cash transfers?

Vikram Patel 11:02

I will Alicia, I will speak to cash transfers, but can I just step back and say cash transfers are not the only way in which you can minimise the risks associated with poverty leading to poor mental health. There's a bunch of things we can do to interrupt the pathway from growing up in poverty and experiencing poor mental health. But let me turn to cash transfers. Cash transfers are a terrific example of addressing one of those pathways we talked about earlier, which is income insecurity. There can be nothing more, more damaging to your mental health, nothing more humiliating to an individual, not to be sure what you can eat tomorrow. And I believe that cash transfers are a very powerful policy tool. It's something you can do here and now which many countries are already doing to help stave off that kind of uncertainty. Cash transfers actually have a history that goes much before mental health. They're primarily being used in the health field to motivate, for example, people to do things that the government wants them to do. A very good practical example is giving cash transfers to parents if they get their children immunised. These are called conditional cash transfers. But I would say the most powerful cash transfers are the one that anyone is accessing, regardless of any particular behavioural condition, especially, of course, targeted to people who are living in conditions of poverty. And we heard earlier from that wonderful story from Brazil, that is a great example of a country, which has implemented one of the world's largest cash transfer programmes for low income people. And we’re already seeing dramatic impacts of that cash transfer programme on both economic and health outcomes.

Alisha Wainwright 12:44

Well let’s hear from Leonidas again - because his family participated in that very programme. It’s called Bolsa Familia, and it’s a Brazilian government scheme which was introduced to help low-income families. Here’s how it benefited Leonidas

Leonidas Valverde De Silva 13:02

(Portuguese, fading to voiceover)

From what he can remember. He started receiving Bolsa Familia, his family started receiving it when he was about 13 or 14 years old. They received about 300 Brazilian Reais per month. After Bolsa Familia was introduced in their family, they had access to grilled chicken, to salad. But they were also able to have more meals, which really did make a difference. It was also important that even though the amount of money was very small, they could do things like take public transportation. And this is important because it just exposes you to a different type of lifestyle. Even just going to supermarkets there. It feels like it was an important door or entry, also to be able to start to dream more. And some of the dreams are very small. It's like maybe I could leave this smaller neighbourhood and go to live in the city centre. Maybe I could work in one of the shops in the city centre. So he doesn't feel Bolsa Familia really can directly influence your mental health. That maybe the amount is too small to really have a direct impact on mental health. But indirectly, it can really improve your access to culture, to people, to ideas, and that can be really important for mental health.

Vikram Patel 14:32

That is such a moving testimony from Leonidas and I think he again describes in such a such an evocative way, how receiving that modest, it is a modest amount of money in Brazil, can actually be so transformative in terms of the experience that Leonidas and other beneficiaries of Bolsa Familia have in their everyday lives. But here's the interesting thing, Alicia. We are examining the impact of Bolsa Familia on mental health. And our first analyses which are already published clearly demonstrate that families who have received the cash transfer from this programme, the young people in those families have much lower rates of psychiatric hospitalisation, but wait for this. They also have much reduced suicide mortality rates. There is a lot more coming out of this amazing programme of research. But all of it is pointing to proof that giving money to poor people, in fact, not only promotes your mental health, but prevents premature mortality due to mental health problems.

Alisha Wainwright 15:39

Do you think that we would benefit from doing more research? Or do you feel like there's enough research that's been done? And it's just a matter of getting the policies out there and actually influencing some change?

Vikram Patel 15:51

Well, you know, I clearly think not every question has been answered. I mean, you know, for example, this word poverty actually is an umbrella category, there's so many diverse experiences within that category. So I definitely think to understand better how we can target interventions to reach the most vulnerable, the most disadvantaged, the most marginalised, is a continuing task. However, the need to do more research cannot be the excuse not to act now, on what we already know. And I'll tell you what we know enough about for example, cash transfers, to act now. And that is what I think needs to be done most urgently.

Alisha Wainwright 16:31

OK, well here’s someone in another part of the world who’s trying to establish how this could work in reality. We’re about to hear from Crick Lund - he’s someone you’ve mentored for years, so he’s a bit of a protégé perhaps? He’s co-leading a research project called the ALIVE study. This is a multi-country project in Nepal, South Africa and Colombia. It focuses on preventing depression and anxiety in adolescents living in urban areas. It’s the first time a study of this scale has been conducted in low and middle income countries, and it’s not just looking at the benefit of cash transfers, it’s also studying how money COMBINED with other interventions, could help prevent mental health issues in later life.

Here’s Crick to walk us through it. And when he talks about a control arm, he just means a group who don’t receive any treatments or money, so they can compare the outcomes.

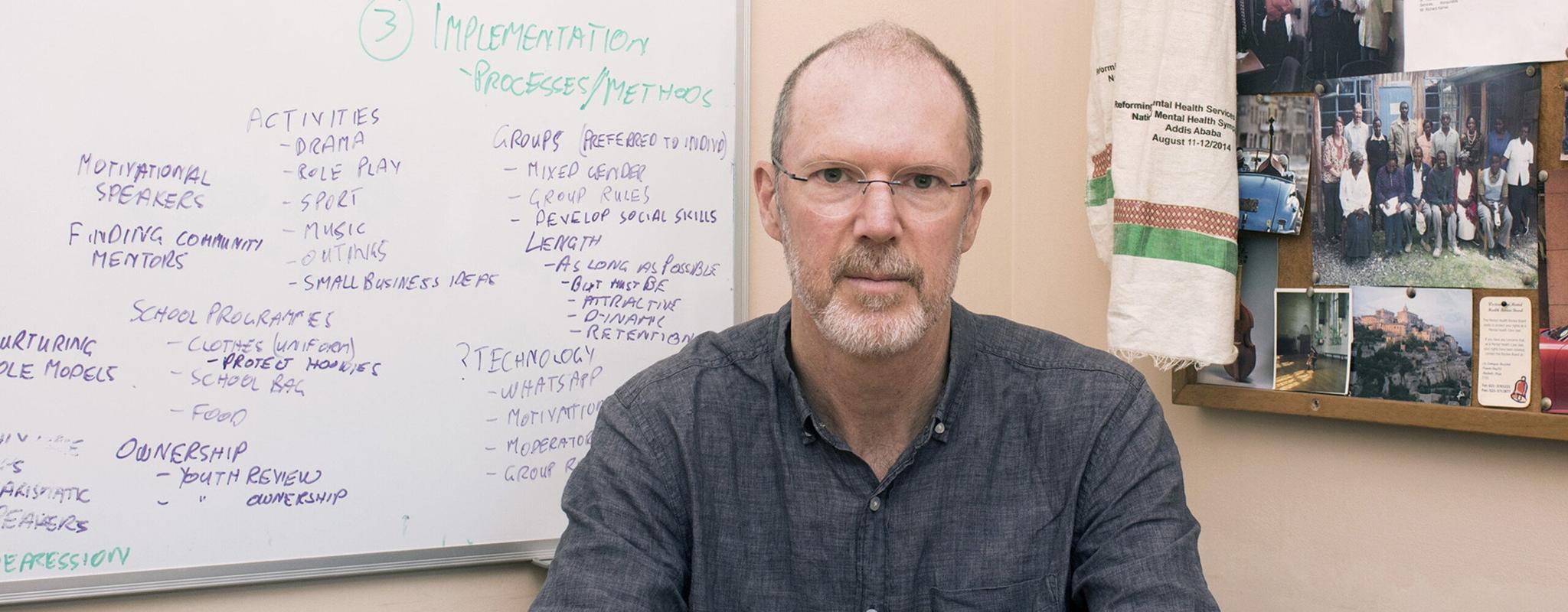

Crick Lund 17:24

The really exciting thing about the ALIVE study is that we have full arms in a randomised control trial. So the first arm is a poverty reduction arm in which participants will receive a cash transfer together with financial literacy, and savings education, as well as developing negotiation skills. We think these are all really important for enabling households and the adolescents living in those households to escape from poverty. The second arm is strengthening self-regulation - helping adolescents to develop the skills to set goals, to learn how to manage emotions, and to manage their impulses, to problem solve more effectively. The third arm - and this is where it gets really interesting - is combining the two. So we combine a poverty reduction component with an intervention to strengthen self-regulation. And then the fourth arm is a control arm. And so what we have with this trial is an opportunity both to test the effects of each of these interventions on their own, for self-regulation on its own, poverty reduction on its own. And to assess the impact of combining the two together. Our hypothesis is that the combination of the two is more than the sum of its parts. And we think that by doing these two things together, we have a much better chance of preventing depression and anxiety in later life. So it's really important to study young people, especially adolescents. Because adolescence is such a crucial developmental stage, adolescent mental health predicts later life mental health. So by intervening early, we have a chance to improve resilience and protect people against the development of later life mental health problems. But also adolescence is a key inflection point. So if you look at the Global Burden of Disease study, where you see the prevalence of depression and anxiety really starting to climb is around the age of 16/17. Some of the things that we hope that young people would be equipped to do, as a result of receiving this intervention is, first of all, in a very practical level, to understand the importance of staying in and completing schooling, because that is a major predictor of earnings and lifelong health. Secondly, developing financial literacy skills to be able to manage money well, to manage budgets. Thirdly, being able to have the psychological skills to manage your emotions, your behaviour, your cognitions, to organise your thinking, in a realistic and positive way. And these are all really important skills for helping young people to grow and develop, and especially in the context of poverty, to be able to move towards escaping from poverty, and having a better, healthier, lifelong trajectory.

Alisha Wainwright 20:19

So Crick’s team isn’t just giving money - this study is also teaching the participants financial literacy and emotional regulation skills - why is this important?

Vikram Patel 20:31

Well, I mean, I think first of all, what Crick describes in the ALIVE study, one of the most interesting experiments that is ongoing, and, you know, I know many of us are waiting anxiously for the results. Because, you know, clearly they point to a very important set of questions that address the mechanisms of how living in poverty affects your mental health. You know, on the one hand, we talked a lot about cash transfers already. But the other mechanism, of course, is your own inner abilities to actually manage your emotions and make decisions in your best interest. And it turns out that there is a real good explanation for this. And it's this when you live in poverty, and I'm gonna go back to the point I made earlier about uncertainty and you know, you don't know what tomorrow is going to bring. Leave aside even next year, you don't even know next month, you're going to be able to keep your home. What do you do when you have money? You spend it now. You don't actually build out a kind of a long-term plan, a long term perspective on how you manage your money

Alisha Wainwright 21:27

You absolutely do not!

Vikram Patel

Yeah, exactly. Yeah, no, because there's a tunnelling of our vision because our vision is constrained by our poverty.

Alisha Wainwright

Right.

Vikram Patel 21:37

What I love about cash transfers is that it actually takes away that tunnel, what it does is, you know, when you got cash transfer, you’re gonna get a cash transfer forever now, and you can plan your life in in a way that doesn't have to deal with doing everything right now using on your money right now, you begin to acquire a longer term perspective, but you still need those financial literacy skills in many ways in order to know how you can use the extra impetus of cash in ways that can actually restore your financial future.

Alisha Wainwright 22:08

So right, it feels like it makes sense for cash transfers and other interventions to go hand in hand - Leonidas had some thoughts on this, so let’s hear from him again now…

Leonidas Valverde De Silva 22:19

(Portuguese fades to voiceover)

He believes like many that treating mental health conditions won't be enough in these places. That mental health is also political. And so we also need social policies that are going to reduce the social problems, which is really an important factor related to mental health. So that of course, right treatment and building clinics and building hospitals that will help support and treat people with mental health conditions is going to be important. But if you don't have the policies in place also to help people and provide social assistance and provide social support, that just won't be enough to help prevent or treat people's mental health conditions. So you have to really also focus on the origin of these problems, too.

Alisha Wainwright 23:09

So there's this holistic picture I'm seeing, and as Leonidas said, it's also a political issue. The problems and solutions are multifaceted, and they require this sort of connected approach. So what are the challenges around this?

Vikram Patel 23:26

So I want to also amplify what Leonidas said, he's absolutely right, in pointing out that you can't address only the treatment, without addressing the origins, he's completely right. That being said, we should also not do the opposite. You know, we shouldn’t only be investing in prevention, because people are going to get mental health problems, regardless of everything you do on the prevention side, you know, we can see this every other medical problem. Also, we shouldn't forget that when you are depressed, or you have a mental health problem, you're more likely to slide into poverty. You've got to also care for people who are already living with a mental health problem. And here, I really emphasise the importance of interventions that can be delivered when they need it. Early interventions is the key here, because we know when you get an intervention early in the emergence of a mental health problem, you have much better outcomes.

Alisha Wainwright 24:20

Why haven’t we been very good at intervening early on when it comes to mental health?

Vikram Patel 24:25

There is a medical industrial complex. You know, we often hear the military industrial complex, there is a medical industrial complex, to the point that the only perspective that prevails and dominates the mental healthcare landscape is a doctor prescription hospital model. However, the good news is over the last two to three decades, there has been a flourishing of new science, science that has investigated how you can deliver mental health care in community settings, using non specialist providers like community health workers, peer support workers, nurses, and so on so forth, and running exactly like the kind of study you heard that Crick described. These randomised control trials that evaluate how effective and how acceptable are these disruptive ways of delivering mental health care? And here's the thing, Alicia. More than 100 such experiments have been conducted around the world, and they all find the same result. Not only is it safe and acceptable, but it's highly effective and even cost saving to deliver mental health care in the hands of appropriately trained and supervised and supported frontline workers. That is the direction we need to travel. And by the way, this is the direction that many governments around the world, the World Health Organisation, and many other agencies have embraced. The science is strong. And I now see the winds of change. Also, in wealthy countries, I see the winds of change in professional guilds. I believe we're at a unique inflection point, to be able to build a community based mental health care system without the resistance that we have faced for many decades.

Alisha Wainwright 26:03

And are you seeing this change in the global south as well?

Vikram Patel 26:07

Absolutely. Some of the most imaginative and disruptive innovations happen in the places where there are the least resources. You know, I often use the analogy, it's much easier to build a house on a vacant plot of land than to remodel a house that already exists. In most of the Global South, there is no mental healthcare system. And thus, this kind of innovation that I described, of deploying frontline workers to deliver mental health care has actually flourished in the Global South. I am very hopeful. In my long career in this field, I have never encountered a period where there is so much political will, where there is so much public concern, and most importantly, where there is a growing sensitivity to the lived experience of mental illness. And I think this is a moment in which we must grasp and compel our governments and our communities to take action.

Alisha Wainwright 27:07

Well, your research and your work is compelling me to want to take part in this movement, because I think what we're discussing today is just so valuable, and not only educating people on the benefits of simple solutions that don't require additional research that don't require more time to really make sure that we have answers. There are things we can do now that don't require a lot of heavy investment. And it's up to sort of the public to engage their governments to implement these changes.

Vikram Patel 27:41

That's right, we need to shift hearts and minds, Alicia. Very many people get extremely cynical or nihilistic when we talk about mental health, there's nothing we can do. We're just pouring money down the drain. That's not true. We are pouring money down the drain, but we're not putting it in the things that actually work.

Alisha Wainwright 27:59

And are there any questions around poverty and mental health that you’d still like to answer in your own work?

Vikram Patel 28:05

Yeah I wanted to say something which has intrigued me for a long time. You know, while it is true that poverty is associated with poor mental health, it is also true that most poor people enjoy good mental health. And I think that's an intriguing observation. And I think it's one that deserves a very different kind of inquiry, which is this. What protects people who are experiencing severe disadvantage? The poor, people who are refugees from a horrible conflict, undocumented migrants in the US, etc? What is it that protects these individuals or groups? Who otherwise should all be experiencing poor mental health, given the enormous disadvantage they've faced. To me, the answer to that question is potentially one of the most important ones that can help us understand how we can improve the mental health of everyone. And interestingly enough, that is a question that has not yet been answered in a compelling way. Here's the interesting thing, you know. People, African American people have faced every single possible insult, that can affect your mental health. And not only in this generation, but over 400 years. Yet, ironically, black people enjoy better mental health than white people in America. I asked, you know, an expert in the field, David Williams, how is that possible? And he said, you know, this is because black people, over 400 years have built ways of connecting with each other, or building community resilience. And he said, a good example is the church. So you know, there are things that point to social intervention, social connectedness, solidarity, et cetera, that actually we haven't studied enough. And I believe we should, because they have great relevance going forward.

Alisha Wainwright 30:02

I was gonna interrupt you to be like, I already know the answer to that one. Because speaking as a black person, I can say that if, you know, I reflect on my life and the adversities that I've experienced in relation to my race, what I do find as something that offers me comfort and mental fortitude is the community of other people who are experiencing and have experienced what I experienced. And two, we like uplift each other in this community. I also was raised in a predominantly religious community with a strong church backing. And I have a really large family. I'm first generation, my mother and father are from the Caribbean and come from large families. So I would love for someone to delve deeper into how these communities are so powerful for maintaining mental health.

Vikram Patel 30:51

You describe what I call social connectedness, which to me is that mysterious ingredient that's impossible to measure in a quantitative way, but which I think underlies the most important mechanism of promoting and protecting every individual's mental health.

Alisha Wainwright 31:10

Thank you so much - I know people can't see but I hope they can hear how much I've been smiling during this conversation because it's really incredible that we're able to take a conversation about the pains of mental health and shape it in a positive, interesting way with active solutions that many governments and communities can apply. Vikram, thank you so much for your time. What a delightful conversation.

Vikram Patel 31:38

Thank you, Alicia. I've really enjoyed this talking to you. You've been terrific as well. I think this has been a fabulous exchange. I've really, really enjoyed this.

Alisha Wainwright 31:50

Thanks for listening to this episode of When Science Finds a Way. And thanks to Vikram Patel, Leonidas Valverde da Silva, Crick Lund… and to Sara Evans-Lacko for her translation work.

I found speaking to Vikram so interesting that I’m already trying to work out how I could speak to him again. It’s left me feeling so uplifted that change is possible, and we can make it happen.

When Science Finds a Way is brought to you by Wellcome.

If you visit their website - wellcome.org – that’s Wellcome with two L’s - you’ll find a whole host of information about the research that’s unearthing new answers to the global mental health crisis, as well as full transcripts of all of our episodes.

If you’ve been enjoying When Science Finds a Way, be sure to rate and review us in your podcast app. And you can also tell us what you think on social media - just tag Wellcome Trust - with two Ls - to join the conversation.

Next time, we’ll be asking whether genomic sequencing could help prevent future pandemics.

When Science Finds a Way is a Chalk and Blade production for Wellcome – a global charitable foundation that supports science to solve the urgent health issues facing everyone.

Show notes

Poor mental health has always been associated with lower socio-economic status, but what if you turned the idea on its head and administered cash transfers as a mental health treatment in and of itself? The scientific research community has long grappled with the lack of major breakthroughs in the treatment of mental health disorders. So could cash transfers hold the key to coming up with a universally applicable and low-cost mental health intervention?

In this episode Alisha is in conversation with Professor Vikram Patel, a world leader in global mental health, who explains the challenges researchers have faced globally in the fight against poor mental health, and the potential of using cash transfers. They hear from an early beneficiary of Brazil’s Bolsa Familia cash transfer programme and meet the professor developing a pioneering new study with young people in Nepal, South Africa and Colombia.

Meet the guest

Next episode

Alisha speaks to Professor Christian Happi about his pioneering use of genomic sequencing during the 2014 Ebola outbreak in Nigeria, and how the technology could unlock the secrets of disease prevention.

Transcripts are available for all episodes.

More from When Science Finds a Way

When Science Finds a Way: Our podcast

Our podcast is back with a third season, uncovering more incredible stories of how scientists and communities are tackling the urgent health challenges of our time.