Episode 10: How can we feed the world with a changing climate?

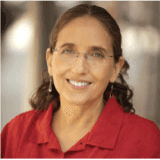

Alisha speaks to Professor Ruth DeFries to discuss how the world has become reliant on a small number of crops (such as corn and rice), leaving us in a vulnerable position if these staples do not grow well as the planet heats.

Listen to this episode

Tafadzwa Mabhaudhi 00:04

I have a dream where one day I walk into supermarkets, and I find all of these, you know, African indigenous leafy vegetables readily available on the shelves. A lot of people still perceive them as poor people's crops. So I have a dream where those perceptions change.

Alisha Wainwright 00:27

Welcome to When Science Finds a Way: a podcast about the science changing the world.

I’m Alisha Wainwright. And I’ll be meeting people with hands-on experience of our greatest health challenges – as well as the scientists and researchers working to make a difference.

On this episode, we’re going to be hearing about the link between climate change and food production - from the ground up.

Because what we farm - as well as how we farm it - has the potential to help transform our food systems in the face of climate change.

As you’ll hear – and maybe you already know – our planet is heating up, and there’s more extreme weather which accompanies this. And it isn’t just a problem for farmers. It’s already affecting every area of agriculture, right along the whole food chain, from planting to purchase. As the planet continues to heat up, it’s going to get a lot harder to grow the food we need to survive.

We also rely on a small number of crops that are produced as commodities. These are often called cash crops. Think corn in the US, maize in Nigeria, rice in India. And that reliance has left us in a vulnerable position.

But what if we farmed in a different way? Could a move towards a more diverse diet help us AND the planet?

Ruth DeFries 01:58

Having that genetic information that plant breeders can use and put into crops, it's just critical. I can't think of anything more critical in the world.

Alisha Wainwright 02:09

That’s Ruth Defries. She’s a Professor of Ecology and Sustainable development at Columbia University in New York, and co-founding dean of the Columbia Climate School. She’s fascinated by how we can use land in a more sustainable way, and her research in India has helped pave the way for a cultural shift. Ever heard of millets? If you have, Ruth might be one of the reasons why.

Ruth is a champion for the value of indigenous, underutilised species of crops. We’ll also hear from an international research project exploring this idea too. Could bringing these crops back into the mainstream help fix our food systems for the future?

First, here’s Ruth to spell out the big picture - how do we grow food now, and how did we get here?

Ruth DeFries 03:08

Over the last 50 or so years, there's been a laser focus on producing more, on increasing the yield of the high producing crops like rice, soy, wheat, maize, you know, those handful of crops. And that is, you know, great success. It's an amazing success story that there's enough food in this world to feed everyone. Whereas in historical times, that may not have been the case. But it is also a real danger zone to us. Because what has happened is that the number of species that we rely on for humanity to feed itself has narrowed quite substantially. So there's something like 40,000 edible species in the world. Yeah. And there's even more potentially edible species in the hundreds of thousands. But what we rely on for human consumption is pretty much a handful, three quarters of the calories for the human diet come from the major commodities - wheat, rice, corn - those three together produce over half of all plant-based calories for human consumption. Chicken, pig, and cattle, the big animal species. So we put all our eggs in a basket of these small number of species. And why does that make us vulnerable? It makes us vulnerable, because we grow those species with a lot of inputs, a lot of water, irrigation, fertiliser, and so on, in places where they aren't so well adapted to the climate, and certainly not well adapted to a future climate. So that genetic diversity that was in all of those species has been narrowed and narrowed and narrowed down.

Another aspect of the way that the food system has evolved over the past decades is that where the main commodities are grown, like wheat in particular, have been concentrated in a few places like Russia and Ukraine, the Midwestern US, the Pampas, Argentina. So we have this high concentration in these few places that the many, many countries around the world rely on for their imports. So when there is an extreme event, or some kind of climate impact, or any kind of impact, like the Ukraine war, for example, that affects those places, then it ricochets throughout the world.

Alisha Wainwright 05:42

Wow. It's incredible that we have set it up that way. It seems highly inefficient and also efficient at the same time.

Ruth DeFries 05:50

Exactly, Alisha, exactly. That's what we call these complex networks of interactions; robust, yet fragile,

Alisha Wainwright 05:58

Robust yet fragile, that is very apt. And when we think about climate change, what kind of relationship do we see between this limited, global food basket you’ve described and global warming?

Ruth DeFries 06:13

Well, in two ways, one is that the whole food system produces about a quarter of all greenhouse gases into the atmosphere. So yeah, it's a big, it's a big contribution to greenhouse gases through methane and through nitrous oxide, particularly. And that happens through a couple of different ways. One is because cutting down tropical forests to grow some of these commodities like soy and beef and oil palm, all that carbon dioxide that was in those trees then goes into the atmosphere. That's one way. Another way is, for example, through livestock, which produces a lot of methane. So there are all these different pathways that add up to the food system contributing about a quarter of greenhouse gases. So it's quite substantial.

On the other side, it's the impacts of climate change on food and food prices. So for example, we have extreme heat that we're seeing in some places - that we know that wheat is particularly sensitive to heat. And right now, for example, we're seeing in the news that in India, which is where I work, so I follow the news, tomatoes are something like 400% higher in price. And that's because of the extreme heat that has occurred and affected the crop. And then all of these increasing prices affect people differently - if it’s the people in urban areas then they’re relying on being able to purchase food, so their prices go up, which can be quite a hardship. And if you’re thinking about the people who are in the places where they rely on their own food for much of their subsistence, then the impact can certainly be extremely tragic, and lead to - or at least trigger - migration, and people needing to seek other places because they just have no option. All of that can have an impact on nutrition - particularly on children’s nutrition which affects them and stays with them for life-long. So there's both the contribution of the food system to climate and the impact of climate on the food system.

Alisha Wainwright 08:29

And if prices go up massively, that’s a huge problem for so many people in the world who can’t afford food. I mean, four out of ten people on the planet can't afford a healthy diet. So clearly this is a HUGE issue. Well, let’s hear now from someone who’s on the front line of all this. We spoke to a farmer - on her farm - in a coastal province of South Africa, who's already seeing some of the impacts of climate change.

Makita Magwaza 08:59

My name is Makita Magwaza. I'm a farmer from KwaZulu Natal. My father was a farm garden boy. And my mother was a kitchen girl. That's my history. And my father was a farmer, he brought us up doing farming. That's why I inherited that from my father and my mother. I'm farming the crop and the vegetable, in the land of plus or minus three acres. Climate change, it hits a lot. I do observe a lot of challenges, like heavy rain, hails, and all of a sudden, the big heat, very hot days, it changes - very hot. And if it is cold, it's very cold, the snow and all that - that dries up, the production is running low.

Alisha Wainwright 10:02

So farmers, like Makita are already seeing these more extreme changes in temperature and in rainfall. But why is this relevant to everyone?

Ruth DeFries 10:12

Well, Makita is on the front line of climate change, as we heard, and she's facing climate change in the context of feeding her family and selling her crops. The irony of this is that the small scale farmers like Makita, who are who are facing climate change, are the most food insecure on the planet. But that does affect everyone.

So we often think about the impact of climate change as just the impact of heat, or drought, or a flood on the production itself. And that is certainly a critical aspect of the impact of climate change on food production. But there's so many other impacts all along the chain within the within the food system.

There’s so many different pathways, and generally those pathways work through the impact on prices.

So if there's a loss of production from some climate event, and prices increase, and then people can't afford that food, which could lead to migration, or just not having not being able to afford a nutritious diet. And, in many parts of the world, people spend a very large proportion of their income on food, so a small increase in price will really impact them a lot. But, this impact of climate change on food prices, affects everybody,

Alisha Wainwright 11:39

So, when we think about this handful number of crops, have we left ourselves vulnerable to the impact of climate change on our food systems by relying so much on such a limited number of crops?

Ruth DeFries 11:54

Yes, because it's that genetic diversity that provides the range of plant traits that allows plant breeders to be able to develop new crops, develop traits that are resistant to drought, or resistant to pests, or resistant to water logging, or - the different traits that the plants need. So they are relying on the genetic diversity for that information about how to get those traits into the, into the crops. So when we sort of narrow down that genetic diversity, we essentially narrow down our options. Yeah - opportunities.

Alisha Wainwright 12:33

So your research has focused on how we can use land in a more sustainable way. So what is the research telling us about what we need to do?

Ruth DeFries 12:45

Well, it’s quite obvious that some crops that people are growing in different places are not suitable for the current climate, much less the climate in the future. So how do you shift that whole setup? So my research - what I've been focusing on in recent years has been in one particular type of crop, in one particular place, and that is on the millets in India. So these are pearl millet, finger millet, small millets different kinds of millet, that are known to be climate resilient.

Alisha Wainwright 13:22

I feel like I have heard that you're a bit of millet aficionado, but for someone who is maybe - I don't know that I've ever had millet before. Can you describe to me what it looks like and what it tastes like?

Ruth DeFries 13:35

Well, you may have had it. Sorghum is kind of a type of millet. If you’ve had gluten free bread - it's kind of dry actually. If you’ve had, you know, gluten free products you most likely have had sorghum.

Alisha Wainwright 13:50

And millet is a gluten free -

Ruth DeFries 13:53

Yes, millets are gluten free, they have low glycemic, they're highly nutritious and most importantly, they're climate resilient because they evolved in semi-arid conditions. So they evolved a type of physiology that enables them to grow with less water. They're basically seeds of grass, which is what wheat is. And they've been in diets for a very - thousands and thousands of years they've been staples in semi-arid parts of the world.

Alisha Wainwright 14:26

Would you call a millet an ancient grain?

Ruth DeFries 14:30

I would - I mean, that's kind of an over-romanticised term. But it certainly is a traditional staple from China, from the Indian subcontinent, from Africa.

Alisha Wainwright 14:43

I personally feel like ancient grains is a bit of a buzzword - why is the conversation around millet not just a trend?

Ruth DeFries 14:52

Well, because its climate resilience is so critical. And it's been very, very interesting to watch the evolution of this discussion in India where millets have been over the last decade sort of considered to be low-status or not aspirational. People would aspire to eat white rice, because that's what, you know, wealthy people eat. It's gotten this unfortunate reputation as being a low-status cereal. So there has been a real reversal at high level policy over the last seven, eight years, where millets are now very high on the agenda. They were on the menu of the White House when the Prime Minister visited a few weeks ago. So they've gotten a lot of attention for two reasons. One is because they're climate resilient, and we've seen so many examples now where it's clear that the current system of over-reliance on rice and wheat is setting society up for a lot of vulnerability. So that’s clear. And also the nutrition.

Alisha Wainwright 15:57

Looking at the bigger picture, do you think these types of indigenous varieties can give us back that diversity that you mentioned?

Ruth DeFries 16:06

Diversity is the key. And we learned that from nature, we might think we can outsmart nature but we really can't. And having diversity really is what maintains the resilience and ability to adapt to conditions that we don't even know what will be like in the future.

Alisha Wainwright 16:25

Well let’s hear now from a research project that’s looking at this very issue. It’s called SHEFS, which stands for sustainable and healthy food systems and is taking place in the UK, South Africa and India with the aim of finding healthy, accessible, affordable and sustainable ways of producing food. Tafadzwa Mabhaudhi is a research group leader on the South African arm of the project. He’s been researching whether bringing back more native plants into the mainstream - species which are often neglected or underutilised - whether that could help provide both nutritional diversity and climate resilience …

Tafadzwa Mabhaudhi 17:10

Well, South Africa is one of 17 megadiverse countries in the world. We've got millets, we've got sorghum, we've got indigenous pumpkins, we've got wild watermelon, we've got wild mustard. We are really endowed with a lot of agro biodiversity, like my favourites; taro, bambara, cowpea, lebleb, pigeonpea, chickpeas, beautiful maize, and rices ... And yet none of these crops and fruits are available to purchase. So the challenge now with climate change, the water scarcity risks are increasing in the region, temperatures are increasing in the region, we're seeing massive land degradation, which means we've got more fragile or marginal soils, resulting in more frequent crop failure. Whereas some of these indigenous or underutilised crops could provide stabler yields with less crop failure in similar circumstances.

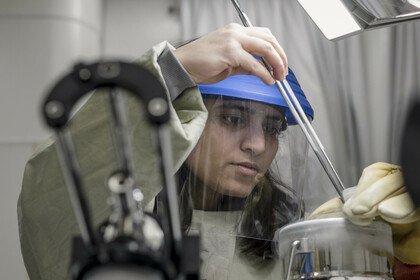

We assessed a range of crops and established 15 priority underutilised crops that we thought exemplify the best of these crops, and have the best probability for success. A lot of the trials that we do, we call them ‘on farm’ trials, the farmers themselves assist with managing the crop in the way that they would manage it themselves. When we have this, we only collect enough for what we need for sampling. And the rest we donate back to the family. So there's always been a strong relationship with the communities that have given us access to these crops. And if we are successful in getting these crops noticed, and creating the market, these communities will be the first to benefit.

I have a dream where one day I walk into supermarkets, and I find all of these, you know, African indigenous leafy vegetables readily available on the shelves, you know, being sold. And I also have a dream where we take back that pride in our diversity. There is still an issue of stigma around these crops, a lot of people still perceive them as poor people's crops. So I have a dream when those perceptions change. I really enjoyed working in SHEFS. It brought in a new dispensation in terms of north-south relationships, where it is not the north bringing knowledge and solutions to be tested, or implemented in the south. But it was more of us saying, you know, South Africa is a research site. The UK is a research site. India is a research site. No one had any superior form of knowledge than the other. And no one had better solutions than the other. So it was a very equitable partnership. And I think that's a big example for many other multi-country projects.

Alisha Wainwright 20:21

That's a lot of crop diversity. What are your reflections on hearing Tafadzwa?

Ruth DeFries 20:28

Well, I just love what Tafadzwa said about building pride in the incredible megadiversity, one of 17 megadiversity countries in the world, South Africa is. And you know, that's the pride that has been stripped away by the focus on the big commodity crops over the last decades. So I just love that he is working towards building that pride and, from multiple aspects, from the point of view of, of being able to commercialise those crops so that farmers can have more income and people can benefit by having those crops available. And also by improving the nutrition of the farmers themselves. So I just really share his dream and love that he said that.

Alisha Wainwright 21:18

So why is this diversity so important in the face of climate change? And just in general, why do we need this diversity?

Ruth DeFries 21:30

Well we need this basket of options, so that the traits that are adapted to a changing climate, pests that that we need the plants to be able to be resistant to, we need that genetic potential to be able to breed into crops. Another aspect of the indigenous varieties is that they're adapted to their local conditions. So they have evolved along with the pests that have evolved in those places. So they're less susceptible to pests. So having that genetic information that plant breeders can use and put into crops, it's just critical, I can't think of anything more critical in the world.

Alisha Wainwright 22:15

Tafadzwa also raised some important points about how SHEFS facilitates the research. There's an equity of their research partners that's spread across the globe; India, UK, South Africa. And also the SHEFS team works closely with farmers on the ground level. Can you talk a little bit about why this sort of equity would be really important?

Ruth DeFries 22:40

Yeah, so those who have the knowledge are the people on the ground. Farmers are the best scientists. They know what crops grow where, when, and they could see when their crops are being impacted by - and so valuing that knowledge is incredibly important, and making sure that we all can learn from it, but that knowledge is theirs.

Alisha Wainwright 23:07

So Makita Magwaza is one of the farmers who’s growing - and eating - indigenous crops. Let’s hear from her again

Makita Magwaza 23:17

I do ancient farming, like indigenous amadumbe, sweet potato, bambara nut, even ground nuts, that I can rotate all the food for the household, and food for selling, and make money for living. To keep ancient agriculture is cheap, is not costly. And you are using the normal thing what goes there, like make your own compost and plant it, and it agrees on that. When we're planting the new plant, then you have to see what is in the soil. And most of the things we're not even using the chemical things, in ancient food, and I can get my own seed. Keep their own seed, not buying the seed, and is cheaper. My special favourite is bambara nuts, ground nuts. Sometimes I just boil it, enjoy it as a snack. Sometimes I can eat this food when I'm having lunch. And like when I boil it, I smash it, put some things few things like, healthy and indigenous, not like spicy. I can have my bamabara nuts with the herbs, and drink water, then my stomach is full. What helped me in all that is my seasonal calendar, I do the record and know what hit me, if the hail started, then I planned separate stages not just planned for one time, so that I do have, if I got the heat or hail or something, then I can get the harvest in the next batch.

Alisha Wainwright 25:09

I want to go to Makita’s for lunch. I don't know about you.

Ruth DeFries 25:11

Yeah, I’ll join you on that.

Alisha Wainwright 25:14

It's amazing to hear how Makita is keeping these old growing and cooking traditions alive. And also educating herself about how to work better with the changing climate. So when you hear about projects like this, does it give you hope?

Ruth DeFries 25:32

Well, yeah, Makita brings up a really important point about the indigenous varieties that she's growing that don't require a lot of costly inputs - fertiliser, water, pesticides.

Alisha Wainwright 25:45

Keeping your own seed?

Ruth DeFries 25:47

Yeah, which can really strap farmers. And that's because those indigenous varieties have evolved in those places to adapt to the conditions. So they don't depend on a lot of inputs, as opposed to species that you're bringing from far away, and you're gonna have to give them water, you're gonna have to ward off the past. So I love that she, she talked about that.

What she's doing for the world is incredible. Makita and farmers like her are really the stewards of that diversity, and not only keeping those species alive by planting them and cultivating them, but having the knowledge about how they grow, where they grow, how to process them, how to store them. So Makita is really, really a great hero, and farmers like her, for the world, because they are keeping this diversity alive, under enormous odds.

Alisha Wainwright 26:43

So we spoke to a regional expert - Ama Essel - about this project. Ama is a Ghanaian public health physician specialist, who’s worked in the climate arena for 15 years - from the community all the way up to international level. She’s an IPCC lead author and a climate change negotiator for Africa. She had some thoughts on what steps need to be taken next.

Ama Essel 27:13

Two things come to my mind. How do we commercialise what she's doing? How do we make the seeds available for a larger number of people? What is the solution? Is the solution encouraging people to have little gardens in their backyards? How do we practically do it so that it reaches more people than it's currently doing? We need to also talk about how we package it to become more attractive to more people, because people want to see food in a certain way that makes it look attractive and delicious, too. So I think that's where the research community needs to come in - only in looking at the seeds, and making it more resistant and available - packaging, production line, those kinds of discussions. How do we work with the farmers? How do we implement the farming practices around these indigenous groups? We need to have well informed policies and action plans, appropriate institutional arrangements need to be put in place. We say there's so much research, just gathering dust on shelves, how do you bring in the policymakers to make sure that this research is actually going to be implemented?

Alisha Wainwright 28:24

Food for thought there – getting policymakers on board… and Ama made another great point too. How DO we scale this? And how do we package these indigenous crops to make them more appealing to consumers?

Ruth DeFries 28:40

Well, Ama has asked a really key question, how do we scale and maintain the access to everybody, so it's not too expensive? And, you know, it's easy for us to think about farmers like Makita in a romantic way. But I think we are at the danger of trapping the small-scale farmers in the past, when in fact they could benefit from mechanisation, from processing, from market chains, from getting more value added. Like often farmers like Makita are selling the raw fruits, vegetables or grains, and then the middle person who's coming in and buying them, and then making them into fancy products that show up in restaurants and on shelves - that's where the profit is coming from. So how do you shift that so that the farmers themselves can use technology to get that high value for themselves? And how do we keep this balance between commercialization and not going so far in the direction of food gentrification.

We see that with teff, for example, which a very, very small, tiny, tiny, tiny seed that is so important as a staple in Ethiopia. So when we go into Ethiopian, wonderful Ethiopian restaurant and have injera that's made from teff. So teff has become more attractive in urban settings, so it has become expensive for the farmers themselves to buy. So, what's important here is the balance and commercialising that provides income for the farmers. But also to keep the balance from food gentrification.

Alisha Wainwright 30:24

So how do you shift some of the profits and market share back from the middleman to farmers like Makita?

Ruth DeFries 30:31

Well, there's a lot of vested interests at play. So it's easier to say than actually achieve, but you know, farmer-producer organisations, you know, farmers working together, farmers getting credit, efforts that give them the capacity to have the technology and scale up.

Alisha Wainwright 30:49

Have we seen any examples of indigenous crops that have been successfully mainstreamed and scaled?

Ruth DeFries 30:57

Well, yes, and that is quinoa. You know, I wouldn't have thought in my wildest dreams, when I was younger, that quinoa would be one of the common features that that we have available to us. So 2013, I think it was, was the United Nations International Year of Quinoa. So quinoa being native to Bolivia, and grown in Peru. And what happened is a sort of good news story, bad news story, is that quinoa became very popular, but because it became more commercial, it became grown in a lot of different places. So even in the US, there's quinoa that is grown. And so that reduced the prices and was competition for the farmers who were preserving many, many different local varieties. So it became a boom and bust situation. But it is a really good example of increasing diversity in our basket of options.

Alisha Wainwright 31:52

If we zoom out to a macro perspective, given we’re seeing such rapid changes in our climate, what do you think the future looks like for food, and are you hopeful?

Ruth DeFries 32:05

Yes, cautiously optimistic. There is increasing recognition of what have been called neglected and underutilised crops, or some sometimes called orphan crops. There is increasing recognition that these are not just neglected and underutilised, but they’re opportunities and provide really the basis for the future.

I worry about the big vested interests that are at play, whether it's a sugar lobby, or a corn lobby, or wheat lobby that makes it very hard to break the status quo. It's a big worry. And I really, really worry about farmers like Makita, who are working so hard, and keeping this diversity alive, and subject to these extreme events that we are seeing, and we're going to see more and more of around the world. So having insurance, having alternative ways to provide income, having some support system is really needed.

It's easy to think that we are living in the worst of times. And certainly, we do have a lot of challenges with climate change, and you know, autocracies, and all these challenges that we face, but step back for a minute. We do not see famines on the scale that we've seen in the historical past, although very sadly, we see conflict driven famines. This increasing yield and drop in price has reduced world hunger. We have scientific tools to discover these plant traits and to adapt and to breed new varieties. So we have a lot of tools if they're put to use to feed people, and support livelihoods rather than maximise profits. So can get pessimistic and think we live in the worst of times. But there have been advances. And there's a lot to fix in the food system. But I'd say that I would be cautiously optimistic, but a lot of attention needs to be paid to this critical, critical issue is how humanity is going to feed itself. So agricultural research has been declining in funding. So it's gotten less priority. So that is clearly something that we need. We need the political and social will to recognise that our food system would benefit all of us by diversifying and valuing that diversity. So there's opportunity to create a system that values the diversity more than we currently have.

Alisha Wainwright 34:41

Having a giant corporation change their systems is a David versus Goliath visual that feels really challenging and would keep anyone up at night if they took the time to really think about it. But what it sounds like you're saying is there are mechanisms and tools and countless farmers like Makita, who are creating solutions. It's just up to our policymakers and these incentivized corporations to adapt to the ever changing times. Would you say that that's pretty fair?

Ruth DeFries 35:13

I would, and also, just going back to what has happened in India over the last few years in this very, very high-level attention to millets, which were ignored for so long. That awaits to be seen how that actually plays out on the ground, but having that very high-level focus, I wouldn't have thought that that would happen. But it has, because of the hard work of many people, of activists and people who have been, you know, really on the front line.

Alisha Wainwright 35:46

Well, that gives me a lot of hope. And it is a great example of what we can hope for to be our continued positive outcomes in the future. Thank you so much for your willingness to help me understand more about this topic on the future of our food and also crop diversity. I feel like I learned so much, I'm equally stressed, but also very hopeful because it's a very clear map of what we need to do. So I want to thank you so much for your time.

Ruth DeFries 36:18

Well, thank you so much, Alisha, and I really appreciate that you've done an episode on this topic.

Alisha Wainwright 36:25

Thanks for listening to this episode of When Science Finds a Way. And thanks to Professor Ruth DeFries, Makita Magwaza, Tafadzwa Mabhaudhi and Ama Essel.

How we produce food is certainly a huge and pressing issue for our future. The challenge to adapt in the face of climate change makes the next fifty years even more important than the progress of the last fifty. And this focus on diversity and indigenous varieties feels like a critical piece of the puzzle - if we can JUST get those in power to take notice.

When Science Finds a Way is brought to you by Wellcome.

If you visit their website - wellcome.org – that’s Wellcome with two L’s - you’ll find a whole host of information about climate change and our food systems, as well as full transcripts of all of our episodes.

If you’ve been enjoying When Science Finds a Way, be sure to rate and review us in your podcast app. And you can also tell us what you think on social media - just tag Wellcome Trust - with two Ls - to join the conversation.

Next time, we’ll be asking whether giving people cash could be the answer to the global mental health crisis.

When Science Finds a Way is a Chalk and Blade production for Wellcome – a global charitable foundation that supports science to solve the urgent health issues facing everyone.

Show notes

With rising temperatures and shifting climates imperilling our crops, the food chain – from planting to the consumer – is under threat. This could lead to higher food prices, poor nutrition, hunger and migration.

Alisha is in conversation with Professor Ruth DeFries, a global expert in ecology and sustainable development, to discuss how the world has become reliant on a small number of crops such as corn and rice, leaving us in a vulnerable position if these staples do not grow well as the planet heats. So how can we encourage climate resilience through crop diversity?

They hear from a multi-country research project which is exploring whether indigenous crops could hold the key to creating more sustainable food systems and meet a South African farmer who is helping keep these old growing traditions alive.

Meet the guest

Next episode

Alisha speaks to Professor Vikram Patel to explore how cash transfers could hold the key to coming up with a universally applicable and low-cost breakthrough in the treatment of mental health disorders.

Transcripts are available for all episodes.

More from When Science Finds a Way

When Science Finds a Way: Our podcast

Our podcast is back with a third season, uncovering more incredible stories of how scientists and communities are tackling the urgent health challenges of our time.