The Covid-19 Anxiety Project

As well as the obvious dangers of infection, Covid-19 has posed a serious threat to mental health, bringing new causes of anxiety and exacerbating many existing concerns.

To show this often-unseen reality, Wellcome commissioned five photographers from five different countries to tell their stories, answering the question: How are you, your family and your friends coping with anxiety related to Covid-19?

Stay up to date

Sign up for emails to get the latest news about the Wellcome Photography Prize, including when the next round will be opening.

Cait Oppermann

Brooklyn, New York, USA

May – June 2020

Click images to open gallery

Cait and her partner confined themselves to their Brooklyn apartment as New York became the world’s coronavirus capital. 'Days and weeks felt both excruciatingly long and impossibly short at the same time as our perception of time changed nearly hour to hour.'

They spent most of their days inside, 'moving aimlessly around the apartment' or on their small terrace, 'restless with anxiety, hearing the sirens of ambulances at least every other minute'. The connection between interior and exterior worlds was striking: 'The overwhelming feelings of uncertainty and loss in the city were palpable even within the walls of our apartment despite being so physically separate from the world.' But they knew that staying inside, and preventing the spread of the virus, was vital work.

Then came the police killing of George Floyd. Cait and her partner, along with many more Americans, were presented with a cause that 'rivalled Covid-19 in terms of urgency and threat to human life' – and a cause that demanded communal action. They dared to venture outside, equipped with masks and sanitiser, to join the protests. 'We felt that the moment required it.'

The streets of New York, already transformed by lockdown, now changed again.

The concerns of quarantine and pandemic mingled with 'an equally new feeling of anxiety associated with re-entering the outside world to protest and resist against police brutality and oppression'.

Cait’s photography viscerally highlights this tension, 'the constant push and pull associated with being concerned for one’s own health and trying to quell an invisible virus as well as one’s own civic duty to fight against injustice and disease of another kind altogether'.

Cait Oppermann, born in 1989, is a New York-based photographer who holds a BFA in Photography and minor in Art History (2012) from the Pratt Institute in Brooklyn.

After graduation from Pratt, she began working in editorial and commercial photography while also continuing to pursue her own projects. Her clients include Nike, Google, Rapha, IBM, GQ Style, The New Yorker, Vanity Fair and Zeit Magazine, among others.

She has worked with an impressive selection of high-profile figures, photographing the likes of Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, Bernie Sanders, Elizabeth Warren, Megan Rapinoe, Naomi Osaka and the United States Women’s National Soccer Team. In 2017, she received a Young Guns award, as well as being named one of PDN’s 30 Photographers to Watch.

As someone who understands and appreciates the importance of investing time and energy into maintaining her own mental health through the years, she is passionate about contributing to the conversation on mental health, as it coincides with the ongoing anxieties and challenges of Covid-19.

Hayleigh Longman

Harlow, Essex, UK

May – June 2020

Click images to open gallery

'I think that the most honest representation of lockdown is the contrast of chaos and calm, the waves of emotions and anxieties that it has held for me.' Hayleigh spent lockdown living with her mum and her mum’s partner in Harlow, and she found herself thinking about 'the coping mechanisms and distractions we use as a way of understanding and processing Covid-19'.

Often the answer was 'productive procrastination' – things like DIY, clearing out cupboards, gardening – that generated a sense of purpose. 'There is a sense of performance in these actions, as we fill our time with activity in order to distract ourselves from the fear and anxiety we were feeling.'

She also found diversion in 'making connections with my community and neighbours, more so than ever before'. This included seven-year-old Harry next door – they entertained each other over the garden fence.

Throughout, most important to Hayleigh has been her mum. The two of them started going for walks – daunting at first, but it became important to them. 'It helped us keep our minds clear and check in with one another, as the house could feel quite small and crammed with us all stuck indoors day to day.'

She also found self-portraiture therapeutic. 'Turning the camera onto myself allowed me to represent the sense of the isolation I felt in the confined spaces of my home. The portrait of myself feels timeless as did lockdown and the days merging into one. Not knowing where the time had gone but not being able to recall what you had been up to.'

Hayleigh Longman is a London-based artist who was born in 1995. She graduated from Manchester School of Art in 2018. Her practice focuses on personal stories and working poetically with complex subjects.

She was awarded the RedEye Graduate Award in 2018 and the Metro Imaging Mentorship Award in 2019. Her work was exhibited at Sid Motion Gallery’s show Fresh Cuts in July 2020. Her early work from The Length of Our Bones project was featured in The Photographers Gallery’s A Story Behind a Photograph, raising awareness of breast cancer.

She started the Wellcome commission during lockdown after losing work and moving back to her parents’ home. The project was a chance to extend her existing practice of turning the camera on herself and her family, though the circumstances are very different. The intimate project considers how the pressure of lockdown shifts as she explores her home, family and community. The project is an engaging reflection on anxiety and mental health, which affects us all. It aims to be relatable and offer reflections of what we are all living through.

Lindokuhle Sobekwa

Thokoza, Johannesburg, South Africa

May – June 2020

Click images to open gallery

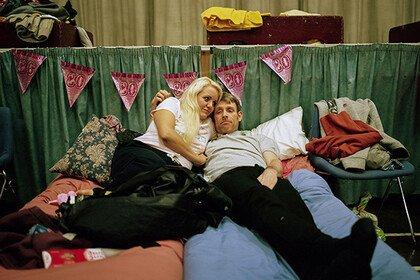

'It was a very lonely birthday.' Like millions around the world, Lindokuhle had to celebrate his special day without most of his loved ones. He was living with his girlfriend's family in Thokoza township, Johannesburg, separated from his mother, brother and sisters.

As the weeks passed it became harder and harder to be apart. 'This has caused much anxiety, with each family member constantly having to worry about the other, hoping and praying that they don’t get infected by the virus.' They have stayed in touch as much as they could, making physically distanced visits when possible, but it’s not the same.

Lockdown has been hard across the township, where homes are small and densely packed together and life is largely street-based. The electricity supply has been unreliable, making things even harder.

Against this stressful background, you have to get creative and entertain yourselves as best you can, such as by playing shadow puppet games with candlelight.

Lindokuhle has found the photography project a prompt for self-reflection. 'I was able to focus on my own life, my own family, and to appreciate the things that I took for granted such as spending time with family, hugging and shaking hands. The project brought into focus the importance of family intimate connections.'

In isiXhosa (Lindokuhle’s native language) there is a saying, 'Liyaduduma Lidlule' – storms come and storms go. 'I am optimistic that this moment too will pass like a storm.'

Lindokuhle Sobekwa is a South African photographer born in Katlehong, Johannesburg, in 1995. He came to photography in 2012 through his participation in the Of Soul and Joy Project, an educational programme run in Thokoza, a township in south-east Johannesburg.

His early projects dealt with poverty and unemployment, and the growing nyaope drug crisis in the townships of South Africa. His ongoing work, as well as revisiting those early themes, also deals with his own life – for example his relationship with his sister, Ziyanda, who died after becoming estranged from her family.

In 2013, he was part of a group show in Thokoza organised by Rubis Mecenat at the Ithuba Art Gallery in Johannesburg. His essay Nyaope was published in the South African newspaper Mail & Guardian in 2014, as well as in Vice Magazine’s Annual Photo Issue and De Standaard the same year.

In 2015, he received a scholarship to study at the Market Photo Workshop, where he completed his foundation course. His series Nyaope was exhibited in the ensuing group show, Free from my Happiness, organised by Rubis Mecenat at the International Photo Festival of Ghent in Belgium, and later in a travelling iteration of the show. The work also features in the book of the same name, edited by Bieke Depoorter and Tjorven Bruyneel.

In 2016, he left South Africa for a residency in Tehran, Iran, with the No Man’s Art Gallery. He also took part in the group show Fresh Produce, organised by Assemblages and VANSA at the Turbine Art Fair in Johannesburg. He is also an assistant to the Of Soul and Joy Project Manager as well as a trainee at Mikhael Subotzky

In 2017, he was selected by the Magnum Foundation for Photography and Social Justice to develop the project I Carry Her Photo With Me. It is thanks to his personal approach in this ongoing narration that he took part in the Wellcome Covid-19 Anxiety project.

In 2018, he received the Magnum Foundation Fund to continue with his long-term project Nyaope, and was selected for the residency Cité des Arts Réunion.

He became a Magnum nominee member in 2018 and associate in 2020.

Manu Brabo

Gijón, Spain

May – June 2020

Click images to open gallery

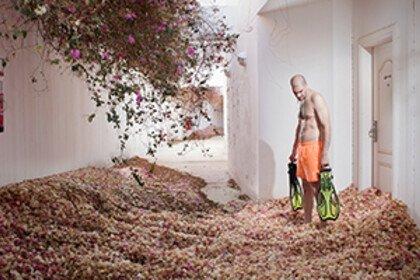

'A story of the fears and joys of a random man who happens to be my dad.' Manu is a conflict photographer from Gijón and he’s used to taking his camera into danger. What he's not used to is when danger comes to his home.

Manu chose his dad as his subject for this project, during Spain’s post-lockdown easing of restrictions, but he soon realised that the story would be about his own fears as much as his dad’s. 'He’s a former chain smoker with a surgery on his throat and carrying as many scars on his body as a bullfighter. He is an easy target for the virus.'

Photographing the pandemic had taken a toll on Manu. 'Dying old ladies on top of their beds in the geriatric, sanitary workers without proper gear, ambulances spinning around the city carrying their load of death and fear. And that bloody graph that never flattens.'

But this wasn’t just another news story: the people he loves, like his dad, were at risk too. 'Is he using the mask properly? Is he washing his hands enough? And if he gets infected, will he be another number on the graph?'

Photographing his dad as he started returning to a more normal life was a way of dealing with anxiety. 'Every time I see him getting dressed (after weeks in his pyjamas) and crossing that door to go painting with his watercolours, or fishing, or taking me out for a beer or anywhere else, I’m simply confronting the fears this pandemic brought me. There’s no way to build a story around what you love if you are not truly honest with yourself.'

Manu Brabo was born in Spain in 1981. He studied art and specialised in photography in 2003.

Starting his career as a freelance photojournalist in Kosovo in 2007, he has since used photography to navigate, investigate and tell about violence and its consequences. Honduras, El Salvador, Libya, Syria, Iraq, Haiti, Ukraine and others have taken the last 13 years of his life.

He currently collaborates regularly with the Wall Street Journal, and has worked with agencies such as Associated Press and NGOs such as Doctors Without Borders.

In his career he has been awarded more than 20 international awards, including the Pulitzer Picture of the Year International and a British Journalism Award.

His work has been exhibited collectively and individually in the most important festivals and photographic centres in Europe and the USA. In 2017, National Geographic created a traveling retrospective of his work in the Middle East, Un día Cualquiera, which attracted more than 20,000 people in Madrid and Barcelona.

He has also worked with Samsung in different projects such as War Reporters Against Breast Cancer, supporting the Spanish Federation of Breast Cancer, and the social campaign with the Prado Museum: Your Culture, Your Future.

Tatsiana Chypsanava

Nelson, New Zealand

May – June 2020

Click images to open gallery

Tatsiana started this project when New Zealand’s two-month lockdown had been lifted – but the easing of restrictions brought its own set of anxieties.

She had spent lockdown with her 13-year-old daughter, Lola, who had got used to being at home – or on 'extended holidays', as Tatsiana puts it. 'She took the ‘stay home save lives’ mantra literally and was not keen to join me on walks or bike rides.' Lola had adapted to socialising online, and she enjoyed the online learning her teachers had pulled together so quickly. 'She was not looking forward to going back to school.'

Going back out into the world meant learning a strange new set of behaviours, from physical distancing to following the official contact tracing procedures.

Lockdown easing meant that Tatsiana could visit her neighbours again and catch up with them. They had all had their own worries, from continuing a course of chemotherapy to keeping a business afloat to simply passing the time.

At times, the lockdown reminded Tatsiana of an earlier period of danger in her life. 'Flashbacks from my childhood in Soviet Belarus brought back memories about Chernobyl fallout in 1986 and the Soviet government mismanagement of the situation.' But ultimately there was no comparison: while the Soviet authorities had been secretive and faltering back then, this year New Zealand has earned international praise for its rapid, open response to the pandemic.

Tatsiana Chypsanava (born 1980 in Belarus) is a member of Women Photograph. While working with New Zealand’s heritage collections she studied for her Graduate Diploma in Photography at the College of Creative Arts at Massey University, Wellington, 2015.

She has contributed to New Zealand Geographic Magazine and Reuters. She has been a winner or finalist in the New Zealand Geographic Photographer of the Year competition 2014, 2017 and 2019 and Photival, Wellington, 2017.

Her work has been published and exhibited in Belarus, New Zealand and Russia. At present, the latest exhibition of her work as a member of Toru Collective is at the Nelson Provincial Museum, New Zealand.

She took on the Wellcome Photography Prize Covid-19 Anxiety Project while New Zealand reached zero Covid-19 cases and was gradually lifting the social distancing restrictions. She sought to share her personal journey living through the pandemic in a country that had gone into lockdown ‘hard and early’.