Chapter 3: Trust in and perceived value of science amid Covid-19

This is the third chapter of the Wellcome Global Monitor 2020: Covid-19

Trust in science and scientists has perhaps never been more important in recent times than during the coronavirus pandemic, as most people have been asked to change their lives in response to recommendations made by the scientific and medical communities. This chapter explores the level of trust people have in science and scientists during the pandemic compared to two years prior and the extent to which people think science informs the decisions of those who offer guidance on Covid-19 – particularly their national government.

Globally, public trust in science and scientists was higher in 2020 than in 2018.

For many people, Covid-19 has highlighted the role of science in fighting disease around the world. Scientists have become more prominent in the media in many countries, providing information and guidance that has affected the day-to-day lives of countless people and ultimately developing vaccines that promise an eventual return to normalcy.

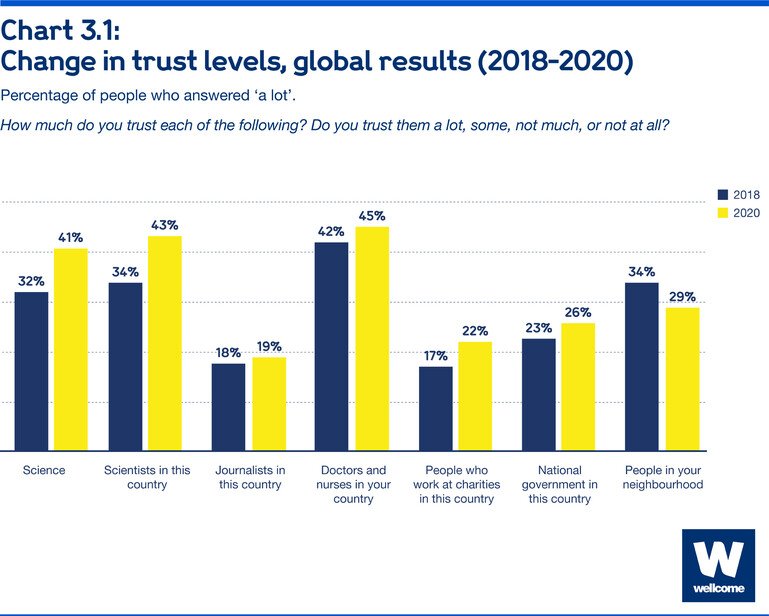

Increased exposure to science and scientists as a result of the pandemic may have influenced public opinion in many countries. Globally, people were more likely to express a high degree of trust in science and scientists in 2020 than they were in 2018: the percentage who said they trust science a lot rose nine percentage points, as did the percentage who place a lot of trust in scientists in their country*.

People’s likelihood of trusting doctors and nurses, their national government and people who work at charitable organisations also increased at the global level, though not to the same extent as trust in science and scientists. Notably, the percentage who said they placed a lot of trust in scientists was significantly lower than the corresponding percentage for doctors and nurses in the 2018 study – but in 2020, trust in scientists was about as common as trust in doctors and nurses.

*As noted in the introduction, the Covid-19 pandemic made it necessary to change the mode of interviewing in some countries from face-to-face (in-person) in 2018 to telephone in 2020. Statistical analysis of the change indicates that it probably had some effect on the results in these countries (see Appendix A). However, the mode-effect analysis of the items measuring trust in science and scientists indicates that the change probably increased the percentage who said they trusted each ‘not at all’ in 2020 more than it affected any other response option. This finding suggests that if the mode change had not been necessary, the results for levels of trust in science and scientists may have risen further than the results presented here indicate.

Chart 3.1: Change in trust levels, global results (2018-2020)

Percentage of people who answered ‘a lot’.

How much do you trust each of the following? Do you trust them a lot, some, not much, or not at all?

As shown in Chart 3.1, people’s neighbours is the only group included in the survey for which trust declined somewhat at the global level, from 34% who said they trust their neighbours ‘a lot’ in 2018 to 29% in 2020. The percentage who said they trust journalists in their country a lot remained flat over the same period*.

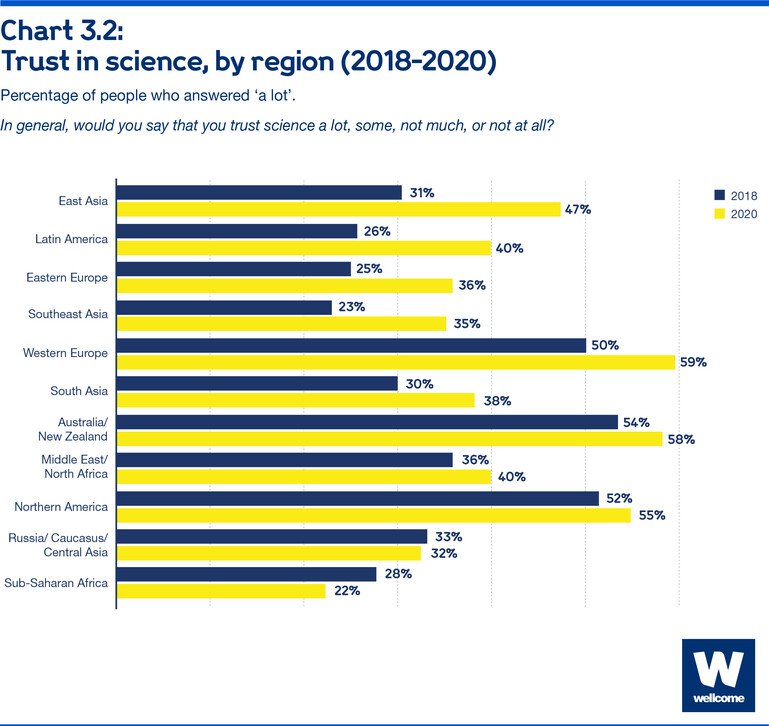

Chart 3.2 shows that the percentage who said they trust science a lot rose by at least 10 percentage points in four regions: East Asia (predominantly China), Latin America, Eastern Europe and Southeast Asia – regions where this proportion was relatively low in 2018. However, this percentage did not rise in two other regions where it had been low in 2018: the Russia/Caucasus/Central Asia region, where it did not change significantly, and Sub-Saharan Africa, where it declined.

*To compare global results for 2018 and 2020, only the countries included in both studies were used in the analysis. Since fewer countries were surveyed in 2020, that meant excluding several countries from the 2018 results for comparison. Thus, the results presented here are somewhat different from those for the same questions in the 2018 report, where those countries were not excluded.

Chart 3.2: Trust in science, by region (2018-2020)

Percentage of people who answered ‘a lot’.

In general, would you say that you trust science a lot, some, not much, or not at all?

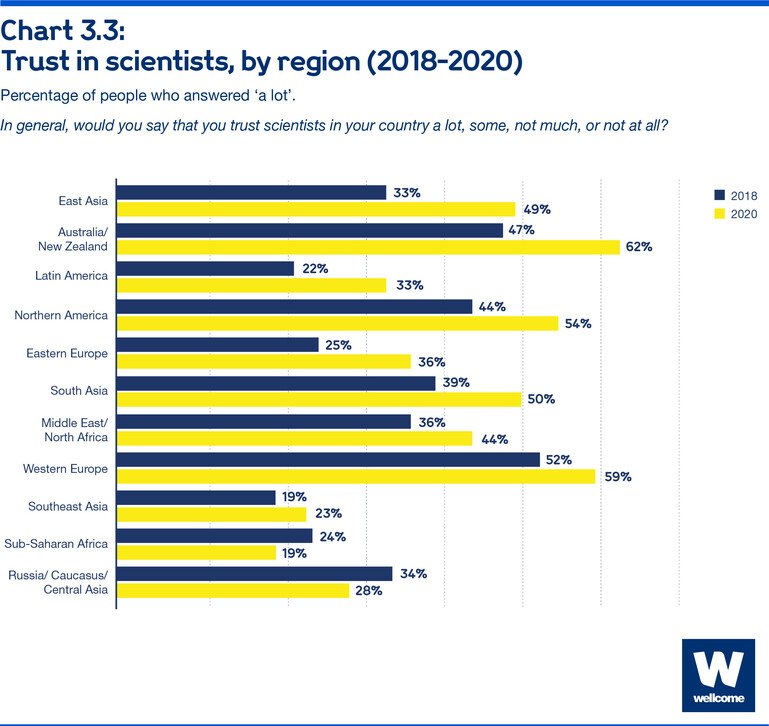

The Wellcome Global Monitor also asked people more specifically about the extent to which they trust scientists in their country. The regional results (Chart 3.3) show a similar pattern to that for trust in science generally (Chart 3.2), with a few exceptions. In Australia/New Zealand and Northern America, the rise was greater for trust in the country’s scientists than for science in general. However, the reverse was true in Southeast Asia, where trust in the country’s scientists rose more modestly than trust in science overall. In the Russia/Caucasus Central Asia region and Sub-Saharan Africa, trust in scientists fell somewhat between 2018 and 2020.

Chart 3.3: Trust in scientists, by region (2018-2020)

Percentage of people who answered ‘a lot’.

In general, would you say that you trust scientists in your country a lot, some, not much, or not at all?

In some cases, people’s trust in their country’s scientists was more closely related to confidence in the government and national institutions than to their trust in science more generally. In Australia/New Zealand, for example, people were less likely to trust their respective country’s scientists a lot if they believed corruption is widespread in their government (61%) than if they did not perceive there to be widespread corruption (73%). However, perceived corruption makes no difference to their trust in science more generally (65% among both groups).

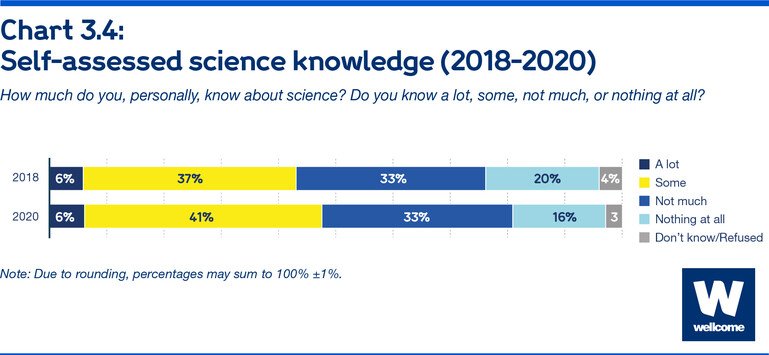

Self-assessed knowledge of science

In 2018 and 2020, the Wellcome Global Monitor asked people how much they know about science. These results were relatively consistent between the two years, though the proportion who said they know ‘some’ about science rose somewhat at the global level, from 37% to 41%, with a corresponding drop from 20% to 16% in the proportion saying they know ‘nothing at all’ (Chart 3.4).

Chart 3.4: Self-assessed science knowledge (2018-2020)

How much do you, personally, know about science? Do you know a lot, some, not much, or nothing at all?

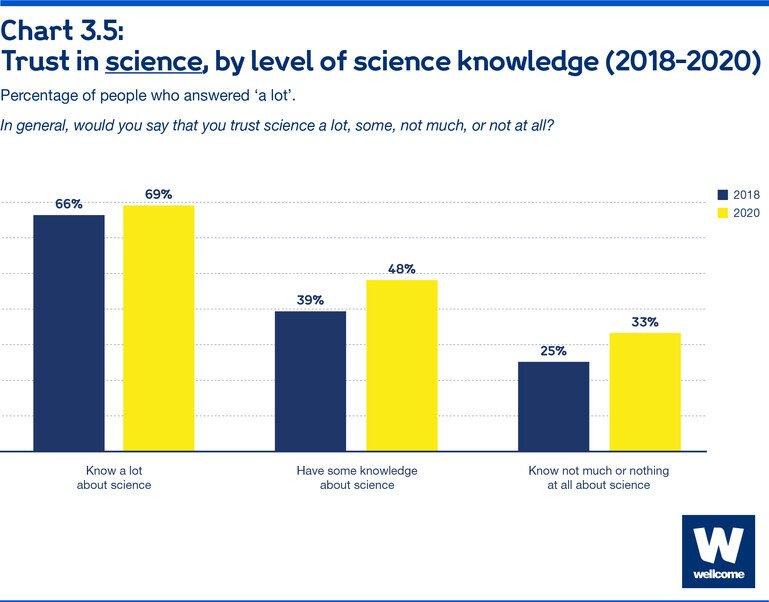

In 2018 and 2020, higher levels of science knowledge were associated with greater trust in science. However, as shown in Chart 3.5, trust levels rose most substantially during that period among people who said they had ‘some’ science knowledge (39% in 2018 to 48% in 2020) or that they knew ‘not much’ or ‘nothing at all’ about science (25% in 2018 to 33% in 2020).

Chart 3.5: Trust in science, by level of science knowledge (2018-2020)

Percentage of people who answered ‘a lot’.

In general, would you say that you trust science a lot, some, not much, or not at all?

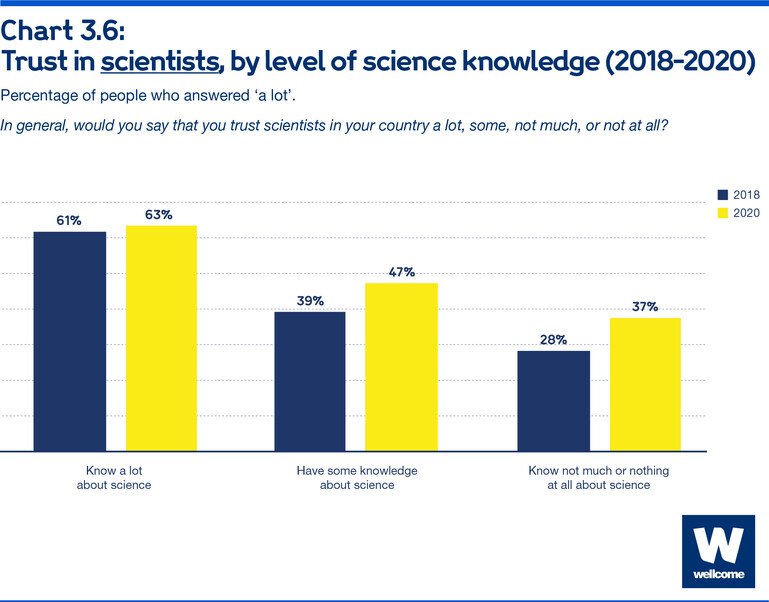

The results are similar for people’s trust in scientists in their country. Worldwide, as shown in Chart 3.6, those who said they know a lot about science were not significantly more likely in 2020 than in 2018 to say they trust their country’s scientists a lot; in both years, the figure was just over 60%. However, trust levels did rise among those who said they know less about science. In 2018, 28% of people who said they did not know much or nothing at all about science trusted their country’s scientists a lot; by 2020, that figure had risen to 37%. There was a similar rise among people who said they know ‘some’ about science.

Chart 3.6: Trust in scientists, by level of science knowledge (2018-2020)

Percentage of people who answered ‘a lot’.

In general, would you say that you trust scientists in your country a lot, some, not much, or not at all?

The change suggests that views of scientists shifted most among people who previously had less direct experience with science but who may have gained an awareness of its importance in combatting Covid-19. At the global level, 43% of people who said their lives have been affected ‘a lot’ by the coronavirus situation put a lot of trust in their country’s scientists, compared to 38% of those whose lives have been affected ‘some’ and 34% of those who said their lives have not been affected at all.

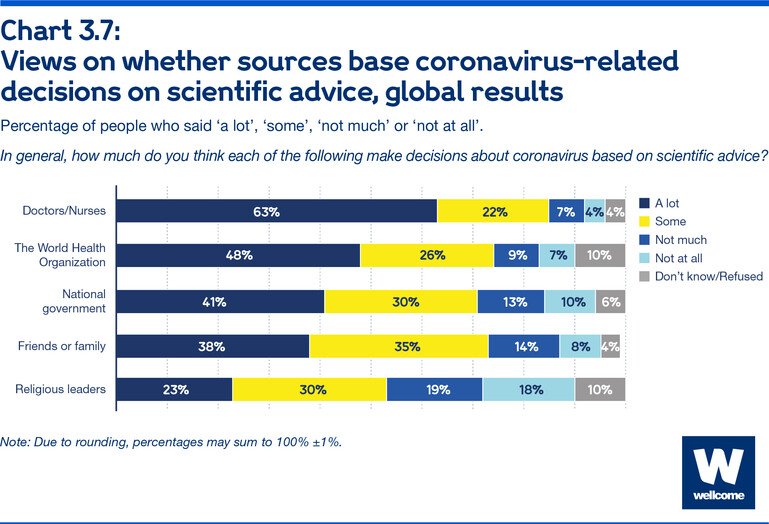

The survey also asked people how much they believe that the sources they have relied on for guidance during the pandemic use scientific advice in their decision-making.

Worldwide, more than six in ten people (63%) said doctors and nurses base decisions about coronavirus on scientific advice ‘a lot’. This figure fell below 50% for the other four sources in the survey: the World Health Organization (48%), their national government (41%), their friends or family (38%) and religious leaders (23%). However, more than 70% felt that each source – except religious leaders – bases their decisions at least somewhat on scientific advice (Chart 3.7).

Chart 3.7: Views on whether sources base coronavirus-related decisions on scientific advice, global results

Percentage of people who said ‘a lot’, ‘some’, ‘not much’ or ‘not at all’.

In general, how much do you think each of the following make decisions about coronavirus based on scientific advice?

This pattern was generally consistent across regions, though people in some regions were more likely than others to say that all five potential sources of advice base their decisions on scientific advice a lot. As shown in Table 3.1, the percentage who said doctors and nurses do so ranged from 84% in Australia/New Zealand to 47% in the Russia Caucasus/Central Asia region. Notably, the Russia/Caucasus/Central Asia region is also where people’s trust in their country’s scientists declined most significantly between 2018 and 2020 (see Chart 3.3), pointing to a general lack of faith in the scientific and medical communities’ ability to coordinate with national governments to provide sound guidance about Covid-19.

Table 3.1: Belief that sources base coronavirus-related decisions on scientific advice, by region

Percentage of people who answered ‘a lot’.

In general, how much do you think each of the following make decisions about coronavirus based on scientific advice?

| Doctors and nurses | The World Health Organization | National Government | Friends or family | Religious leaders | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Australia/New Zealand | 84% | 63% | 62% | 47% | 13% |

| Western Europe | 76% | 57% | 43% | 41% | 13% |

| Northern America | 75% | 57% | 25% | 38% | 15% |

| Latin America | 67% | 57% | 33% | 33% | 26% |

| Southeast Asia | 62% | 40% | 45% | 46% | 22% |

| Middle East/North Africa | 62% | 53% | 40% | 40% | 33% |

| South Asia | 61% | 40% | 45% | 46% | 22% |

| Eastern Europe | 58% | 46% | 29% | 40% | 14% |

| East Asia | 57% | 25% | 22% | 26% | 5% |

| Sub-Saharan Africa | 56% | 61% | 48% | 30% | 36% |

| Russia/Caucasus/Central Asia | 47% | 42% | 40% | 35% | 24% |

Several other findings provide additional insights into people’s perceptions of how much influence scientists have on high-level decisions made by national governments and the World Health Organization (WHO) about Covid-19:

About six in ten people in Sub-Saharan Africa (61%) believed the WHO bases its decisions on scientific advice a lot, second only to Australia New Zealand (63%). And while 10% of people globally said they ‘don’t know’ about the WHO’s reliance on scientific advice, just 7% in Sub-Saharan Africa answered this way – which may reflect the prominent role the WHO has played in supporting health systems across the continent1, including efforts to mitigate the impact of Covid-192,3.

In many countries, people were more likely to believe that the WHO bases decisions about Covid-19 on scientific advice than they were to say the same about their own country’s government. Table 3.2 shows comparisons between these measures in G20 countries where both questions were asked*. Among these countries, only people in Germany and India were significantly more likely to say that their national government bases decisions about Covid-19 on science than to say that the WHO does. (In Germany, this is largely because of the unusually high level of trust in government rather than a lack of trust in the WHO, while in India, a substantial 18% said they did not know about the WHO’s basis for decisions about Covid-19.)

Table 3.2: Belief that the WHO bases coronavirus-related decisions on scientific advice compared with a belief that national governments do so, among G20 countries

Percentage of people who answered ‘a lot’.

In general, how much do you think each of the following make decisions about coronavirus based on scientific advice?

| The World Health Organization | National government | Difference | |

|---|---|---|---|

| United States | 57% | 21% | 36 pts |

| Brazil | 54% | 22% | 32 pts |

| United Kingdom | 66% | 35% | 31 pts |

| Mexico | 68% | 39% | 29 pts |

| France | 62% | 41% | 21 pts |

| Argentina | 56% | 40% | 16 pts |

| Canada | 66% | 54% | 12 pts |

| Italy | 43% | 32% | 11 pts |

| Turkey | 49% | 38% | 11 pts |

| Japan | 22% | 11% | 11 pts |

| South Africa | 69% | 65% | 4 pts |

| Australia | 61% | 59% | 2 pts |

| Russia | 35% | 33% | 2 pts |

| South Korea | 38% | 38% | 0 pts |

| Indonesia | 37% | 39% | -2 pts |

| India | 40% | 45% | -5 pts |

| Germany | 54% | 63% | -9 pts |

*Questions about the government’s response to Covid-19 were not permitted in China or Saudi Arabia.

As Chart 3.8 demonstrates, these two variables were closely related at the country level. In countries where people were more likely to be confident in their government overall, they were also more likely to believe it makes decisions about Covid-19 based primarily on objective scientific advice – a notable finding given that politics and misinformation have complicated government responses to the pandemic in many countries4.

Chart 3.8: Scatterplot exploring the relationship between the belief that the government bases coronavirus-related decisions on scientific advice compared to overall confidence in the government

Percentage of people who answered 'a lot'.

In general, how much do you think [the national government] makes decisions about coronavirus based on scientific advice?

Interact with the data in more detail via the chart below

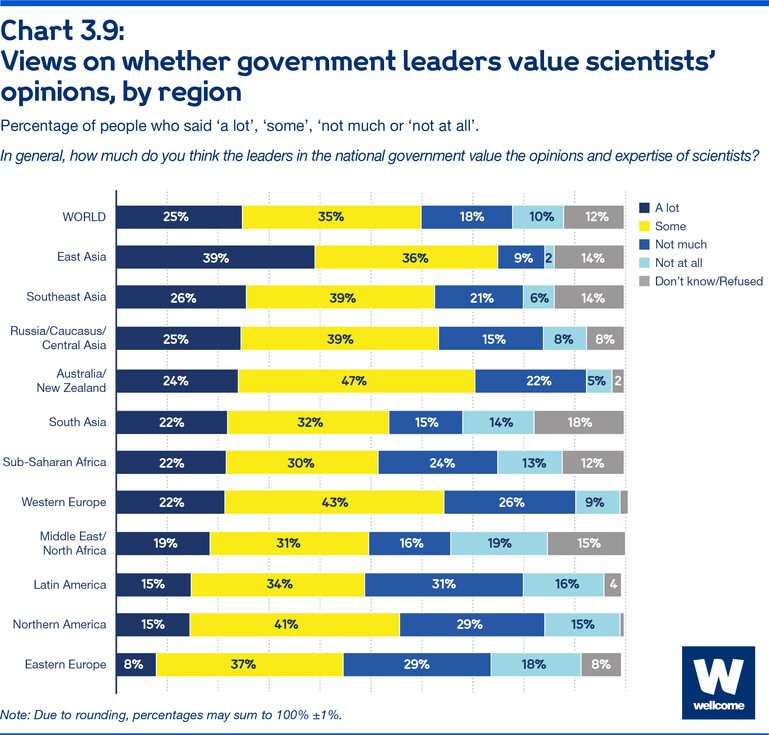

One in four people worldwide said their government values the opinions and expertise of scientists ‘a lot’.

Given the vital role of governments in endorsing and implementing scientific recommendations during the pandemic, the Wellcome Global Monitor asked people how much they think the leaders in their country value the opinions and expertise of scientists.

Globally, as shown in Chart 3.9, one in four people (25%) said leaders in their national government place ‘a lot’ of value on the opinions and expertise of scientists, though an additional 35% said government leaders place ‘some’ value on it. Nearly three in ten (28%) felt their government does not place much or any value on scientists’ opinions.

People in East Asia were most likely to say government leaders place a lot of value on scientists’ opinions and expertise, at 39%. China’s population largely accounted for this high figure;* 44% of Chinese respondents said their government leaders value scientists’ opinions a lot, while 7% answered ‘not much’ or ‘not at all’. However, not all East Asian populations were so certain about their government’s respect for science. Just 3% of Japanese respondents said their government places a lot of value on scientists’ opinions, while 53% said it places some value on them and 37% answered ‘not much’ or ‘none at all’. Polls from Japan have consistently found high levels of dissatisfaction with the government’s response throughout the pandemic5,6.

*Because China accounts for such a large proportion of the total population of East Asia, estimates for this region tend to follow those of China even if estimates for other East Asian countries are quite different.

Chart 3.9: Views on whether government leaders value scientists’ opinions, by region

Percentage of people who said ‘a lot’, ‘some’, ‘not much or ‘not at all’.

In general, how much do you think the leaders in the national government value the opinions and expertise of scientists?

Fewer than one in five people in Eastern Europe, Northern America and Latin America believed their government leaders value scientists’ opinions and expertise a lot, while more than 40% said they do not value scientists’ opinions much or at all. All three regions are characterised by low levels of trust in government and, as with views that their government bases coronavirus-related decisions on scientific advice (Chart 3.8), views that national leaders value scientists’ opinions were strongly related to overall confidence in government.

In 25 of the 113 countries surveyed, including eight in Eastern Europe and six in Latin America, people were significantly more likely to say their government leaders place little to no value on scientists’ opinions than to say leaders place some or a lot of value on them. As seen in Table 3.3, this difference was greatest in Lebanon, where the government has been on the verge of collapse amid a devastating economic crisis exacerbated by the pandemic7.

Table 3.3: Countries and territories where people were more likely to say that their government leaders do not value scientists’ opinions

Percentage of people who said ‘a lot’/’some’ compared to ‘not much’/’not at all’.

In general, how much do you think the leaders in the national government value the opinions and expertise of scientists?

| A lot/Some | Not much/Not at all | Difference | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lebanon | 12% | 74% | -62 pts |

| Bosnia and Herzegovina | 26% | 62% | -36 pts |

| Cameroon | 31% | 58% | -27 pts |

| Iraq | 34% | 59% | -25 pts |

| Hong Kong SAR | 38% | 60% | -22 pts |

| Moldova | 34% | 54% | -20 pts |

| Ukraine | 36% | 55% | -19 pts |

| Gabon | 32% | 49% | -17 pts |

| Tunisia | 37% | 54% | -17 pts |

| Italy | 42% | 58% | -16 pts |

| Nigeria | 37% | 51% | -14 pts |

| Venezuela | 41% | 54% | -13 pts |

| Congo Brazzaville | 36% | 49% | -13 pts |

| Brazil | 43% | 54% | -11 pts |

| Kosovo | 36% | 46% | -10 pts |

| Guinea | 33% | 42% | -9 pts |

| North Macedonia | 38% | 47% | -9 pts |

| Bolivia | 42% | 51% | -9 pts |

| Paraguay | 40% | 49% | -9 pts |

| Romania | 40% | 48% | -8 pts |

| Ecuador | 43% | 51% | -8 pts |

| Chile | 44% | 52% | -8 pts |

| Benin | 37% | 43% | -6 pts |

| Bulgaria | 44% | 50% | -6 pts |

| Albania | 40% | 45% | -5 pts |

Remarkably, in all 113 countries and territories included in 2020, only a minority said leaders in their government value the opinions and expertise of scientists a lot. However, as with the perception that their government bases decisions about Covid-19 on scientific advice, people’s belief that their government values the opinions and expertise of scientists was most prevalent where overall confidence in government was highest (Chart 3.10).

Chart 3.10: Scatterplot exploring the relationship between the belief that the government values the opinion and expertise of scientists ‘a lot’ compared to overall confidence in the government

Interact with the data in more detail via the chart below

Endnotes

- The work of the World Health Organization in the African Region [Report of the Regional Director, July 1, 2018–June 30, 2019]. (2019). Brazzaville: WHO Regional Office for Africa. https://www.afro.who.int/sites/default/files/2019-08/WHO%20RD_Eng%20WEB.PDF

- How World Health Organization is helping African countries deal with Covid-19. (2020, April 3). Africa Renewal. https://www.un.org/africarenewal/magazine/how-world-health-organization-helping-african-countries-deal-Covid-19

- Push for stronger health systems as Africa battles Covid-19. (2020, August 26). World Health Organization. https://www.afro.who.int/news/push-stronger-health-systems-africa-battles-Covid-19

- Transparency, communication and trust: The role of public communication in responding to the wave of disinformation about the new coronavirus. (n.d.). OECD. https://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/transparency-communication-and-trust-bef7ad6e/

- Onomitsu, G. (2020, July 18). More in Japan unhappy with government’s virus response: Poll. Bloomberg. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020-07-19/more-in-japan-discontent-with-government-s-virus-response-poll

- Yamaguchi, M. (2021, May 12). Frustration in Japan as leader pushes Olympics despite virus. AP. https://apnews.com/article/japan-olympic-games-coronavirus-pandemic-sports-government-and-politics-e89382fab53f569d4cbcb49224ef0d21

- Nakhoul, S., & El Dahan, M. (2021, March 26). Analysis: Lebanon frozen by political intransigence as it hurtles towards collapse. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-lebanon-crisis-scenario/analysis-lebanon-frozen-by-political-intransigence-as-it-hurtles-towards-collapse-idUSKBN2BI1YY