Why we need better markers for anxiety and depression

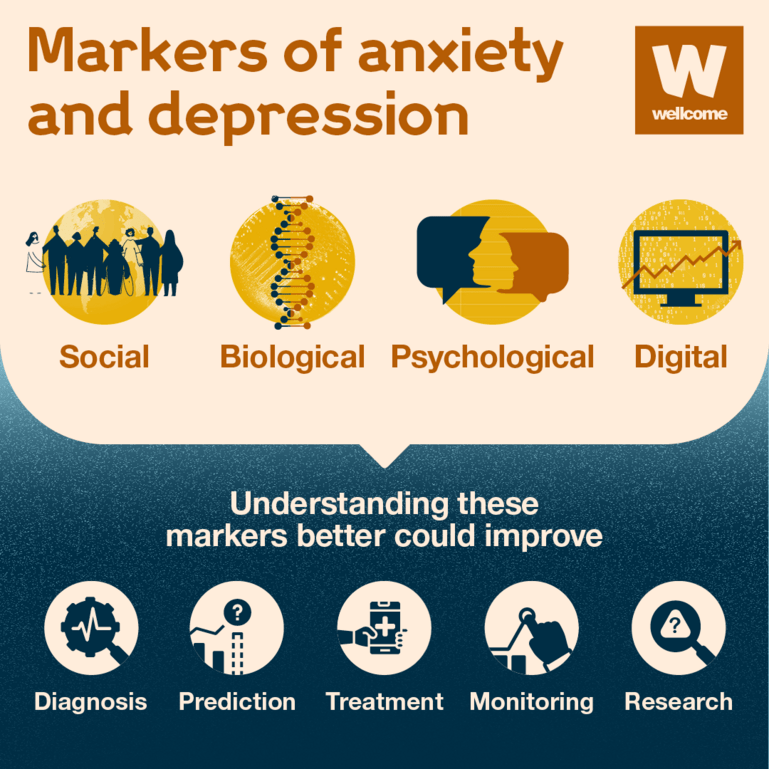

Current methods for assessing mental health conditions still rely on subjective tests, scales and frameworks. New research into biological, psychological, social and digital markers could change that.

Wellcome

The way that we diagnose and treat mental health conditions hasn’t changed much in decades.

Mental health researchers and doctors all over the world still rely on subjective, one-size-fits-all diagnosis frameworks, and treatments that are based on average success and side-effect rates.

Biological, psychological, social and digital markers could be the key to unlocking more effective, targeted treatments.

An overview of different markers of anxiety and depression and how they could improve diagnosis, prediction, treatment, monitoring and research in mental health.

Wellcome

Current tools for assessing mental health conditions

Modern medicine doesn’t yet have objective tests (like a brain scan or genetic analysis) to diagnose mental health conditions. Instead, doctors rely on symptoms reported by the patient and what they can observe.

Recognising these signs and symptoms is not always easy, so there are tools designed to help diagnose mental health conditions:

- Diagnostic or classification manuals (like the DSM-5 or ICD-10) provide a common language and symptom-based categories for doctors to use in diagnosis.

- Mental health questionnaires and scales (like the PHQ-9 or GAD-7) are diagnostic tools for assessing mental health disorders. They are quick and easy to complete and can be self-reported or completed by a clinician or researcher.

These techniques have been used in research and medicine for over a century to communicate, diagnose and treat patients with mental health conditions.

However, as we grow to understand more about the complexities of mental health conditions like anxiety and depression, the disadvantages of these tools are becoming more evident.

Subjective and inconsistent application of the tools means that many differences exist within each diagnostic category. While at the same time, there is an overlap of symptoms across different categories (for example, insomnia is a key symptom of both depression and anxiety).

Using stratification to improve mental health interventions

One solution to these imperfect mental health diagnostic categories is to divide them into further sub-groups of people who share similar biological, psychological or social profiles. This is referred to as ‘stratification’ or ‘stratified psychiatry’.

What is stratification?

Stratification is the process of identifying sub-groups of patients within a disease population based on a common characteristic (for example, genetic profile, risk factors or response to a specific treatment).

Stratification can be used to:

- improve understanding of how a disease works

- identify new targets for treatments

- develop markers for disease risk, diagnosis, prognosis and response to treatments

- allow treatments to be developed, tested and applied to the most appropriate patient groups.

By defining sub-groups, it may be possible to identify which treatments people who share key characteristics are most likely to respond well to and even develop new treatments targeted to this sub-group.

This differs from ‘personalised psychiatry’, which focuses on treating mental disorders based on an individual patient profile rather than a sub-group. While this might one day be the ideal route for delivering mental health interventions, studies are yet to deliver any applications that can be used in a clinical setting – less than 1% are even considered for actual implementation in real-world care.

Instead, stratified psychiatry potentially offers a way to make better use of existing and established treatments by increasing the probability they will produce the desired outcomes.

Other areas of medicine (like oncology or cardiology) have already shown the benefits of developing targeted treatments like this, and we’re now seeing progress in psychiatry too.

Identifying better markers for anxiety and depression

Stratification in mental health could help unlock new and improved treatments and further our understanding of conditions like anxiety and depression. First, we need a way of identifying the sub-groups – that’s where biological, psychological, social and digital markers come in.

Markers for anxiety and depression

Markers in mental health allow objective measurement of an individual’s characteristics in relation to certain conditions. They can be divided into four categories:

- biological markers are characteristics that can be measured as an indicator of normal biological processes or responses to a disease or intervention

- psychological markers are key psychological indicators (for example, mood, stress and sleep quality) that provide information on the likely patient health outcome

- social markers are life events (like family loss) or physical environment factors (like poor nutrition) that can act as an indicator of patient health outcome

- digital markers are technological innovations for self-measurement tools that can help with diagnosis, care management and care delivery.

Biological markers are the most heavily investigated, with ongoing research looking at everything from changes in metabolite levels to neuroimaging and inflammatory responses. While innovations in technology have also led to the development of useful digital markers like the app Actigraph to record sleep disturbances in people with anxiety and Mindstrong, a mood-recording app often used to measure depression.

However, more research is needed.

Studies into the most effective social and psychological markers still lag behind despite growing evidence of important indicators like sleep disturbances and body mass index (BMI). And the overlap between disorders makes it difficult to draw conclusions about promising biomarkers.

Finding the right treatment, for the right people, at the right time

Innovation in the field of mental health stratification could transform the way that we diagnose and treat disorders, but at the moment there is not enough evidence on the best approach to achieve this.

That’s why we are funding research to validate existing biological, psychological, social and digital markers that enable stratification in anxiety and depression as early as possible.

As part of this funding, we want to encourage collaboration across the field of mental health research and build a community of stakeholders from various settings. We have also identified some key areas that need particular focus and development, for example:

- markers that are scalable and have the potential for uptake in low-resource settings

- validation of markers in settings outside of wealthy countries

- the need for a standardised framework and reporting guidelines for stratification trials in mental health.