People worldwide want their governments to value science

During a global pandemic, it’s vital that governments endorse and implement scientific recommendations. We asked people around the world whether they felt their government valued scientific advice throughout the coronavirus pandemic.

Pressing play on the video above will set a third-party cookie. Please read our cookie policy for more information.

Jonathan: Our government was very slow to act. A lot of time was wasted. A lot of lives were lost.

Harun: I didn't believe government policy reflects science well.

Denise: The messages were very conflicting. You wasn't sure how to follow. It actually instilled fear.

Mariska: Whatever the government asks, just follow it first. See where it will take us.

Ali: In Germany, politics really value the advice of scientists. Therefore, we moved on quite quickly from the pandemic. Politics have to invest in scientists, in science, and give them a chance to try things out.

Winner: There have been many scientists criticising the government, but they're being silenced.

Jamie: There have been a lot of attachments of political values to things that we feel like are science and evidence based. My obvious thought and hope is that our government officials work with our scientific experts in a way that is harmonious.

The Wellcome Global Monitor 2020: Covid-19 report shows that people worldwide aren’t certain that their governments value scientific advice.

Valuing scientific expertise

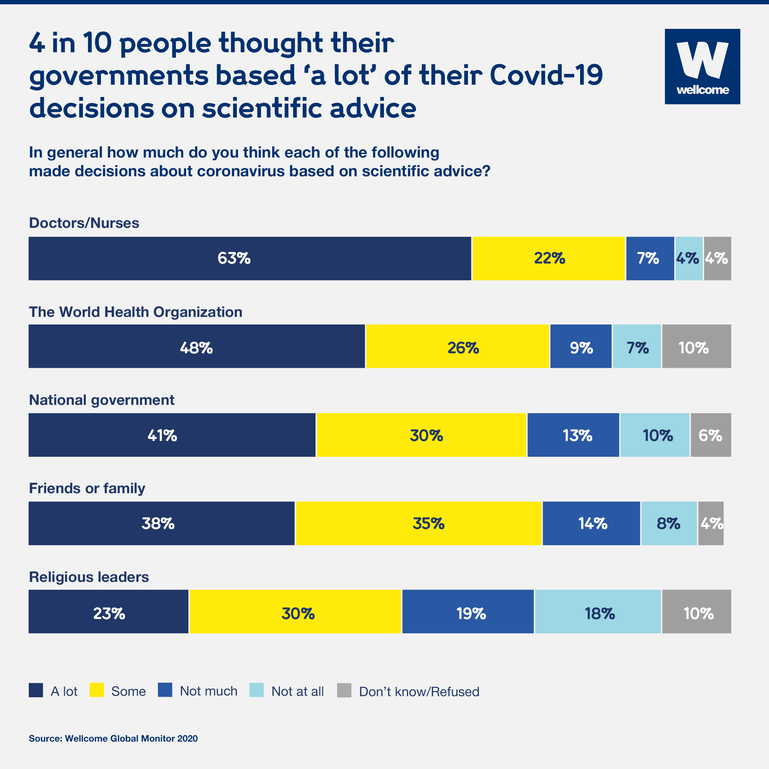

Just one in four people (25%) said leaders in their national government place ‘a lot’ of value on the opinions and expertise of scientists, though an additional 35% said government leaders place ‘some’ value on it.

The report also found a clear link between people’s trust in government and their belief that the government trusts science.

In countries where people were more likely to be confident in their government overall, they were also more likely to believe it makes decisions about Covid-19 based primarily on objective scientific advice.

This chart indicates that trust in governments valuing scientific expertise aligns with general sentiment towards that government.

Following these findings, we interviewed people in four countries – Germany, Indonesia, the UK and the USA – to hear if they think that their government values science.

Follow the science

Despite the UK government’s claims that they would ‘follow the science’ when making decisions during the pandemic, the Wellcome Global Monitor 2020 found that only 35% of people interviewed in the UK felt that the government valued science ‘a lot’ when making coronavirus-related decisions.

“I don’t believe government policies reflect science,” says Harun Tulunay, who was born in Turkey but based in the UK since 2015 and currently works for a health charity. “Up until we had the vaccines, it was very confusing, especially right after the first lockdown. I know many scientists who are opposing the idea of coming out of lockdown fully and the government, unfortunately, didn't follow that advice. People are constantly being kept away from the real data of Covid.”

And many share this view, including Amelia Haspari, an NGO leader and documentary filmmaker from Indonesia.

Amelia Haspari

“In the beginning the government were very complacent when they gave out statements. They were not scientific and didn’t believe the virus was going to come to Indonesia,” she says.

Winner Wijaya, a filmmaker based in Jakarta, Indonesia, agreed.

“At the start of the pandemic, the government really didn't listen to the scientists. Before Covid was widespread in Indonesia, our Minister of Health once said that: ‘let's just pray for Covid to go away’. Then our Minister of Agriculture thought of making anti-Covid necklaces containing eucalyptus leaves. This was said to be able to prevent Covid if you wear it.”

Winner Wijaya

Transparency

Early denial, lack of transparency or conflicting messages have been felt across nations as governments juggle how to relay information to their people while scientific discoveries about the pandemic play out in real time.

In a recording of an interview on 19 March 2020 between Washington Post journalist Bob Woodward and then US President Donald Trump, said he had played down the risk from the beginning. “I still like playing it down because I don’t want to create a panic,” reads one quote.

These recordings, which came to light six months later, highlight a clear misrepresentation of scientific facts related to the danger the virus posed. And this conflict of information was felt by the public.

The Wellcome Global Monitor 2020 found that just 13% of people surveyed in the USA reported that they felt their government listened to scientists ‘a lot'.

Ashley Adams

“I don't feel that the US government trusted science during the pandemic,” says Ashley Adams a sound mixer from California. “I felt immense pressure that they were trying to get the nation to follow suit and not trust it as well. I felt like the severity of it was downplayed for a majority of the time.”

Jamie Yabuno, currently a resident physician in Los Angeles, USA, has been working on the frontline since the pandemic began. For her, the early Covid-19 and science scepticism from the government has negatively impacted the country’s pandemic exit strategy.

Jamie Yabuno

“I really think that there have been a lot of attachments of political values to things that we feel should be science and evidence based,” she says.

“I think one of the greatest challenges that I’ve witnessed throughout this whole pandemic was watching a lot of the political aspects get attached to things like the vaccine rollout. I think that it’s really added a lot of challenges for the general public to understand science and what our experts are saying.”

Clear, decisive communication

A report by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) from July 2020, highlights that an initial hesitancy by governments to “communicate decisively, even about the uncertainty and unknowns surrounding the pandemic has left space for misinformation”.

The report suggests that instead, governments should be clear about uncertainty, as it “is important to convey scientific advice that is subject to change with emerging evidence”.

In all 113 countries and territories included in the Wellcome Global Monitor 2020, only a minority said leaders in their government value the opinions and expertise of scientists ‘a lot’.

In Germany, 31% of people surveyed felt that their government valued scientific advice ‘a lot’.

“I think that in Germany, politics really value the advice of scientists,” says Ali Farrokhian, a camera assistant who was born in Iran and moved to Germany when he was 14.

Ali Farrokhian

“If I compare the Covid pandemic in Germany with other countries, for example Iran where I was born and where, unfortunately, the politics and the science had two different opinions, I think that our politics in Germany did a really good job and the scientists are highly respected.”

The Wellcome Global Monitor 2020 found a clear link between the public’s belief that their government valued the opinions and expertise of scientists and their confidence in the government.

If governments want to gain back public trust, they need to ensure that their policies around Covid-19 – and any other infectious diseases – are informed by science.

The people we spoke to agreed.

“Covid showed us that each government really needs to have a scientific board actively taking into policymaking,” explains Harun. “They should actively engage with the scientists on everything related to the public health and take them into consideration.”

Harun Tulunay

Ali called for transparency and for governments to educate the public on the issues as they arise. “I think the most important is that decision makers and politics are illuminating society about everything and talk openly about the actual problems and where we are standing and what our plan for the future looks like,” he says.

For Jamie, who continues to work on the frontline, ensuring a strong link between government policies and expert advice was key. “My hope is that our government officials work with our scientific experts in a way that is harmonious,” she says.

“Experts are experts for a reason. They've studied this all their life. They've spent years and years of training in order to better understand these things. We should take the opinions and the knowledge of our scientific experts and implement them.”

The value the public place on science and scientists is clear, but how governments use their advice is not, and governments – not scientists – are those responsible for the wellbeing of their citizens.

"The Covid-19 pandemic has thrust scientists into the spotlight, where they have provided information and guidance affecting the day-to-day lives of billions of people,” said Lara Clements, Associate Director, Public Engagement & Campaigns at Wellcome.

"Trust has always been intrinsic to public health and success can only be achieved when communities are open to and readily understand the science. This vast dataset can offer huge potential to learn how the public relate to science, particularly during this crucial stage of the pandemic."