How is AI reshaping health research?

Artificial intelligence (AI) has the power to reshape science and health. Three experts share the potential benefits and pitfalls of AI in health research.

The last few years has seen AI deliver therapy, assist surgeries and discover superbug-killing antibiotics.

Soon, AI could be able to identify potential new drugs and diagnose diseases with even greater precision and accuracy. These innovations hold huge potential to advance the field.

As with any disruptive technology, opportunities come with risks.

What is AI?

Artificial intelligence is the simulation of human intelligence in machines.

It encompasses a wide range of technologies and techniques that enable computers and other machines to perform tasks that typically require human intelligence, such as analysing data to identify patterns or make predictions.

How might AI improve health research?

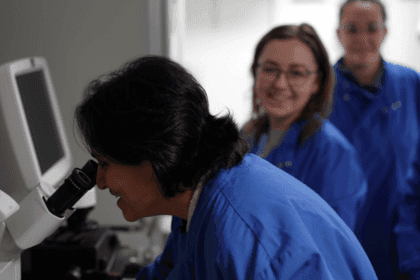

AI systems can analyse mountains of data extremely quickly. They need minimal human input and can identify patterns and anomalies that researchers might otherwise miss.

With increasingly large and complex datasets, AI has fast become an invaluable tool, particularly in drug discovery. Data-driven and AI technologies could help shorten the drug discovery pipeline and reduce costs.

Research areas where there are lower financial returns and that lack incentives for investment, like drug discovery for rare diseases and those affecting low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), could really benefit.

With ever more powerful technology at their disposal, researchers have been able to process data at speeds previously unimaginable.

Priscilla Chan of the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative has gone as far as saying that this revolution in technology could “help scientists cure, prevent or manage all diseases by the end of this century.”

An example of this step change in data processing and analysis speed is the Human Cell Atlas. This international research project is an effort to create a reference map of all the cells in the human body, which could transform our entire understanding of biology and health.

Technological advancements and AI allow researchers to analyse vast amounts of genomic data in a fraction of the time it would have taken in previous years.

AI and bias in research

As with all novel and disruptive technologies, the rapid adoption of AI has positives and negatives.

One of these risks is related to the data which AI is trained on. For example, datasets might not account for lived experience or they might not be representative of diverse populations.

The danger of this becomes evident when AI is translated into products. For example, when self-driving cars were less able to identify pedestrians with darker skin tones.

There’s also a risk that relying on AI to interpret data will lead to outputs that researchers don’t themselves understand.

According to a survey of 1,600 researchers conducted by Nature, 69% said AI tools can lead to more reliance on pattern recognition without understanding.

Wellcome’s Bioethics Lead, Carleigh Krubiner, notes that "on one hand, there's AI’s potential for good. It can expand on and amplify what we as humans alone can do and know to improve health.”

“But there's also a real danger of the misuse of some of these technologies, the more pernicious aspects of reinforced bias and the 'black box' of not understanding what's going on behind the technology to generate the outputs."

This lack of understanding could lead to a lack of accountability. This could erode public support and trust in health research.

Mitigating AI bias in research

"If you’re training your AI on existing datasets, we know the evidence we have is disproportionately skewed to represent certain populations, namely middle-aged white men,” says Krubiner.

“Without mitigation, machine learning will reproduce and amplify those biases, with potentially disastrous effects for populations underrepresented in the data.”

Improving representation and accounting for lived experience in datasets is crucial.

Anna Studman, Senior Researcher at the Ada Lovelace Institute, is leading work on the impacts of data-driven systems and AI on healthcare.

Interviews with people experiencing poverty or chronic health conditions showed that “the nuance of lived experience doesn’t come through in clinical datasets,” says Studman.

But it’s not always as simple as collecting more data.

Studman says that lack of trust in healthcare systems and institutions is particularly evident in marginalised populations. Organisations using health data need to earn trust from the communities they serve.

Studman believes that greater transparency is needed. “Explaining to people why and how that data would be shared and used is important, especially for people who are digitally excluded or feel that innovations in digital health are being pushed on them.”

Getting AI right is particularly important in health care settings.

The unprecedented speed of the digital transformation of healthcare systems often means that “time-strapped clinicians have to quickly get on board with new technologies that are parachuted in,” Studman explains.

Using AI thoughtfully

With its vast potential to speed up processes, cut costs and generate insights, there’s no doubt that AI will continue to be used in health research.

Researchers must take care to:

-

identify and reduce bias in datasets

-

account for lived experience in their data

-

understand the outcomes of their algorithms

-

consider the applications of their research

Shuranjeet Singh, Lived Experience Consultant at Wellcome, says there’s a role for lived experience expertise to shape AI use throughout the research pipeline: “Lived experience expertise can inform the choice and development of the datasets, how learnings are going to be applied and how to flag risks.”

“Ultimately, AI is just a tool: it's only as good as the data it’s trained on.”

Sometimes the most thoughtful way to use AI is considering if you need to use it at all.

“When you have exciting new technology, people want to use it for all sorts of things, even if there is a much simpler, more cost effective and often better way to do it,” says Krubiner.

In 2022, the Wellcome-funded Global Forum on Bioethics in Research (GFBR) focused on 'Ethics of AI in global health research'. The background paper, case studies, governance papers, and meeting report are available on the GFBR website.