Episode 8: One scientist’s journey to respecting indigenous customs

Danish geneticist Professor Eske Willerslev and Dr Shane Doyle, a member of the Crow Tribe in Montana, USA, join Alisha to discuss the possibilities and pitfalls of ancient DNA research and how to build mutual trust and respect between indigenous communities and scientists.

Listen to this episode

Eske Willserslev 00:04

I came in totally naive and also unprepared. Entering these communities, and finding out how the past, and how their ancestors… the meaning to them, to living people today in these communities, was totally new to me.

Alisha Wainwright 00:26

Welcome to When Science Finds a Way, a podcast about the science changing the world.

I’m Alisha Wainwright, and on this series, I’m meeting with scientists and researchers who are actually making a difference, as well as the people who have inspired and contributed to their work.

On this episode, we’ll be talking about the potential – and the complications - of Ancient DNA research.

Believe it or not, sequencing the genomes of people who lived thousands of years ago can give us useful clues for improving health today.

We can find surprising connections between modern day populations; improve understanding of how we've adapted over time; and even uncover why some populations are more susceptible, or more resistant, to certain diseases.

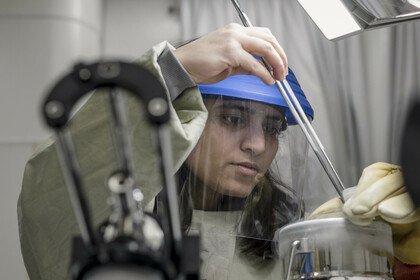

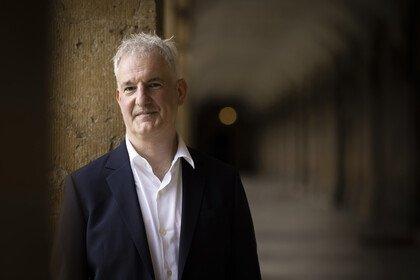

Today I’m speaking with Danish geneticist, Professor Eske Willerslev. In 2010 he led the team that first outlined the DNA of an ancient person, using some very old hair trimmings – but we’ll get to that.

This kind of research Eske pioneered can go in unexpected directions, and lead to surprising discoveries. But one of Eske’s discoveries was that mapping a genome in a lab is only part of the work here. His studies of ancient DNA led him to Australia and the Americas, working with indigenous communities. And that meant navigating cultural sensitivities around ancestry, and engaging with communities who have memories of unethical, colonial science practices of the past.

Hearing his personal journey, you’ll see that this is complicated, controversial stuff. And it’s not a technical problem to be solved in a test tube – it requires a strong relationship of trust between researchers and communities. So, how do you build that?

Shane Doyle is a member of the Crow Tribe in Montana, who worked with Eske on an ancient DNA project in the area, and he joined our conversation to explain what that relationship’s been like. I mean, how do you react when a Danish geneticist approaches you with some ancient remains and says are related to your tribe?

Shane Doyle 02:43

This is momentous, because it changes everything about the way science has, and will, view native people on this continent, and in this state.

Alisha Wainwright 02:53

It was inspiring to hear about the partnership between Eske and Shane.

Eske is the first one to admit that he has made mistakes in his research. But through learning from those mistakes, he has become a passionate advocate for scientific collaboration with indigenous communities. And it really is a collaboration. Eske used the word exchange – learning from the communities just as they learn from his research.

His friendship with Shane is an example of that. There was laughter and real honesty on this call. And a lot of optimism and excitement over where this DNA from the past could lead us to in the future.

Alisha Wainwright 03:38

Eske and Shane, it's great to have you both here. Shane, we're going to bring you in just a little bit. So please don't go anywhere.

But I’d like to start by asking Eske about how you sequenced the first human genome - which was a 4000-year-old Greenlander. And you got that DNA from an unexpected place? Right?

Eske Willserslev 04:01

Yeah, I mean, it was in 2010. So we did the first ancient human genome, and it was from a tuft of hair. Human hair found in Greenland - years before actually, it was found years before. Everybody had forgotten about this hair, so.

Alisha Wainwright 04:20

Do you know what kind of hair it was? Do you know if it's like nose hair, or like, hair off the head?

Eske Willserslev 04:24

No, no - it was, it was hair from the head, it was somebody who got a, who basically got a haircut.

Alisha Wainwright 04:30

Oh, really?

Eske Willserslev 04:31

You know, a guy who got a haircut 4000 years ago, and it was thrown - the hair was thrown into a dump, you know, and - where, where it survived, and nobody had paid much attention to it. So people had forgotten about it. I had been at the museum - at the National Museum in Copenhagen and asked for material from these very early peoples in Greenland, in the Arctic. And they said, well, there's not really much around, and I had been up in northern Greenland, looking for materials myself - didn't find anything. And suddenly, I learned about this hair, which was basically lying 10 minutes from where I'm living. And well, we got it, and we retrieved for the first time a genome sequence. It means, it's kind of the entire DNA sequence, right? From a past human. And we could see from this study that the first peoples that settled the Arctic was not the direct ancestors of present day Inuit peoples, right? It was amazing in two ways. First, it showed it's possible to do ancient human genomics, which people didn't think was possible due to contamination problems, right? So, it showed that with this new technology, next generation sequencing, that it was actually possible to do the genomes of past human beings. And secondly, this particular study showed that if you went back 4000 years in time, the world that we knew in the Arctic - right - was very different. It was occupied by people who were very different from, from the peoples that are living today. In other words, it showed us that the world that we know of today was actually not the same - if you want - just 4000 years ago.

Alisha Wainwright 06:22

Wow. And all of this was discovered from something that was essentially right under your nose?

Eske Willserslev 06:30

Exactly. Totally. Lying in a drawer in a museum, right?

Alisha Wainwright 06:36

Okay. So now my question to you is, do you never throw anything away, out of fear that it could have the answers that you're looking for?

Eske Willserslev 06:43

I would say, definitely. I mean, that's a great learning from recent years’ genetic studies, in ancient genetic studies is, no, don't throw things away, right? There have been museums that have been, you know, occupied by all kinds of stuff. And they were, they say - let’s clean the closet, right? We need to get space for our new thing.

Alisha Wainwright 07:08

And you’re in there being like, don't do it, don’t do it.

Eske Willserslev 07:12

Don't do it, don't do it. It will turn out to be precious many years after, I’m sure.

Alisha Wainwright 07:18

That's so incredible, that’s so incredible, never throw anything away.

Okay, let’s zoom out from that single hair and take a wider view. You mentioned a few of your discoveries from sequencing that genome, but speaking generally, what can we find out by analysing ancient DNA?

Eske Willserslev 07:36

Everything, I mean, I've used it for a number of years to understand, you can see the human past, I mean, when two different human groups meet each other and mix with each other. But we also use it, you know, to reconstruct how nature and an ecosystem reacts to climate change, when it was warmer, for example, in the past. We have recently been using it to track disease-susceptibility, right? I mean, why is a disease risk different across different human populations? How can you explain this?

So you can use it to many things, in order to understand, you know, disease risk, genetic makeup of people, changes in environments and extinctions as well, right? I mean, we've looked at - why did the mammoth and big, ice-age mammals, why did they go extinct? For example, something that has been heavily discussed. Was it climate change, or was it all human overkill? And we believe, based on our studies, we can say it was driven by climate change and not human overkill, for example.

Alisha Wainwright 08:40

Wow, so it can really tell us a lot. And while it’s helping our understanding of the past, we can kind of apply that to issues we’re facing now and into the future. But the question is, you know, where do you start with this kind of research? How does one go out and find ancient DNA? And how do you even know where to go?

Eske Willserslev 09:00

So we are having expeditions very often into the wild. I mean, this summer I’ll go to the most northern part of Canada, for example. The islands up in high Arctic Canada, to take samples. And there you're going with tents and guns and everything, right? And in other cases you are going to museums, where there's already collections available. And then you're using that material. So, it depends on the question you want to address, right? So for example, if you want to understand the first people of the Americas, for example. Well, in that case, one way to go is to basically find ancient human skeletons. The type of material you're looking for depends on the question you want to ask. If we want to ask about climatic changes, and the impact on the environment, we are taking sediment samples of the past, and retrieving DNA, and using that for reconstructions.

Alisha Wainwright 10:01

Okay, so you sequenced an ancient human genome for the first time in 2010. And that obviously opened up a lot of research possibilities. But while a lot of your colleagues focused on European history, you started two studies in Australia and the Americas – which brought you in contact with the indigenous communities there. And the way these communities think about their history, and the remains of their ancestors – that’s very different to how you were thinking as a scientist, right?

Eske Willserslev 10:34

I mean, I came in totally naive, First of all. Naive, and also I would say, unprepared, I mean, I'm Danish and in Denmark, you know, everything that is older than 100 years of skeleton material or human remains are free to research, right? Which says something about - you can say - our attitude in Denmark to our ancestors, right? It's really an object for research, right? So, entering these communities and, you can say, finding out how the past and how the ancestors, their ancestors - the meaning to them, to living people today in these communities was totally new to me. I also, I would say, entered this world, I guess with a view, which I think is very typical for most scientists. And I was, you can say, raised, I guess, in that belief, namely, that all humans, modern humans, originated in Africa some 500,000 years ago, spread out of Africa between 90 and 60,000 years ago, and spread to the rest of the world. In other words, you know, we all have one common history, and many scientists at that time, including myself, had kind of the view, you know, well, the human history belongs to humanity, right? There shouldn't be a particular group of people who should prevent the studies, or the learnings, etc. And I would say I, over my encounter, over my experience with these communities, I totally changed my mind. I mean, radically.

Alisha Wainwright 12:24

But at first, as you mentioned, you were maybe naive. When you were in Australia, did you feel that, as you were interacting with these communities, you ever made any mistakes?

Eske Willserslev 12:36

I made a lot of mistakes, I would say, along the way. For example, in Australia you can say we started the research. I went there, right? I should have done it before. Before the start, right? I mean, so we had the permission to do it. And I had never been to Australia in my entire life. I didn't know much about Australia and Australian history. And we had the legal permission to do it. And then we actually, one of my colleagues said, I think it was a student or something - a postdoc from New Zealand, who said, are you crazy, guys? I mean, what are you doing? You need to, you need to go and talk to these people. I mean, don't you understand that there've been many people before you who wanted to do genetics on Australians, and they said no? And then I was like, oh, shoot, we need to do something about this. And, and then I found out, you know, this hair sample was collected by a guy called Hadden, you know, basically, around 1900, right? And I found out, well, where was the hair sample exactly from? I found out that there was a group of Aboriginal Australian communities that kind of were the - you can say the body you needed to get in touch with. And then I sent them a letter. And to my surprise, they responded positively and said, yes, please come down and explain to us what you're doing. I mean, I had no conception, for example, of how poorly these peoples have been treated. And not only had been treated; are treated. But what I experienced was amazing. Because despite, you know, this horrible treatment, and the, you know, that these peoples had undergone, and been - and by researchers, by the way - killing them, chopping off their heads, sending them back to Europe, all this they had experienced and still, when I came there, they treated me with the greatest kindness. So I went down there and they, you know, they had a council and they took me out to the bush, showing me kangaroo tracks and how their ancestors lived, etc. It was amazing. It was just amazing. And then they basically gave me the endorsement. And I asked afterwards, why did you give it to me? Given that all these other scientists that had got a no, right, that had gone there? And they said, well, there's basically two reasons, right. One is that you flew, you came half across the world to meet with us, right? And showed us this respect. And secondly, you're Danish. If you had been Australian, or British, or American, you wouldn't have got it, because, and this is because we don't really have any known colonial history in my country. And, I brought them also, I brought representatives to Denmark. We - they saw the labs, they saw, you know, how we work. And when we released the results, we did it in Perth, together with the elders, right. It was, I think, a huge success. But in my early times there, I mean, I didn't realise the importance, I would say, of showing the respect by actually going and asking before - even though you have a legal right - I didn't realise the importance of the process.

Alisha Wainwright 16:11

Okay, I want to bring Shane in here. But first a quick background on how you came to work together.

Shane is an academic, educator and community advocate. He’s a member of the Crow Tribe in Montana, in North America, and that’s where he met Eske, as part of an ancient DNA project. This project sequenced the genome of the Anzic child. That’s the name given to the remains of a baby that was found in Montana in 1968, and is around twelve thousand, seven hundred years old.

And Eske found that this baby, which was thought to be of European heritage, was actually closely related to living native communities in the Montana area - communities like the Crow people.

Shane, what was the reaction among your tribe when Eske approached you to say, “Hey, we have these ancient remains that are related to you?”

Shane Doyle 17:03

Yeah, back in 2013, when we first went to Crow, there was a mixed bag there, I think. But the ceremonial community believed that the boy should be reburied, and they wanted to take part in it. But the tribal government, at the time, was opposed to participating in the reburial because they felt like that was not a Crow tradition. And that was another disagreement that we all had, you know, because we felt like that was a Crow tradition. And so yeah, not everyone agreed back in 2013, about what we should do with the, with the remains, or with the evidence o - there was a lot of disagreement on every level, I think. But, again, the people who were most traditional and most respected in the community for their knowledge of ceremonies, and leading the community in that way, supported it. And so to me, that was all I needed.

Alisha Wainwright 18:05

What IS the right way to make the case for this kind of ancient DNA research to indigenous communities like the Crow tribe? How do you navigate these potentially complicated discussions?

Shane Doyle 18:16

Yeah, I think, you know, it's a great question, because it's a political question. You know, I think it can change with the political winds, you know, whoever's in office at that time, or whoever is the tribal college president at that time, their opinion is going to win and rule the day because Indian Country is such a small community. So very few people can really make or break these kinds of projects. And you know, when you get folks who are, you know, advocates for this kind of work, they can find support for, for these things to move forward. But if you don't, then they'll just squash it. You know what I mean?

Alisha Wainwright 18:57

Do they give you a reason?

Shane Doyle 18:59

I mean, everything under the sun. You know, we were accosted one time, when we went to Fort Belknap, Eske and I, first, the tribal college president put us in front of this lady who wasn't even a tribal member, she was a white woman, and she just like, went off on us about how we were stealing from the community, and trying to exploit them, and in front of all these tribal college students in this little public meeting, and it was kind of like, oh my gosh, you know, this is kind of what we're up against. And it's hard to navigate around that. And so I think at the end of the day, you know, Native people have to make up their own minds about this stuff. And, you know, I think as they get more educated, as we become more aware of what Eske has done, which has always been positive, I think. There have been no negative outcomes that I can think of from his work. Uh, and you know, I wanted to speak to that as well, because as Northern Plains people, you know, our tradition, our ceremonial tradition was to go up on mountaintops, by ourselves, and stay there with no food or water for four days and nights. That's not the kind of culture that acts because of fear,, you know. That ceremony in and of itself, is really testimony to that. And I feel like doing this kind of research with DNA is a lot like that. Because you have to be, in a sense, fearless of what you're able to find out about yourself.

Alisha Wainwright 20:26

That is so beautiful, primarily, because you are taking a community practice, a behaviour from - how long would you say that that's something that's been happening in your tribe?

Shane Doyle 20:41

Time immemorial, yeah. Since the beginning.

Alisha Wainwright 20:45

And I love that you're taking it from the beginning and recontextualising it to 2023, you know. Because beyond the ceremonial experience itself, it's about being fearless and about having an open mind and being willing to, to learn and grow. And I think that that's really beautiful. Because I think, you know, as we move through time, and you know, things are constantly changing, it feels like at such a rapid rate, you kind of have to go back to the basics of your beliefs, and recontextualise it for the changing world. So I think that's really beautiful. And thank you for sharing that.

Shane Doyle 21:22

Thank you.

Alisha Wainwright 21:23

Eske mentioned that by the time he came to Montana, he’d already made some missteps in his research, and learned from them. When you met him, what did you make of his approach?

Shane Doyle 21:33

Well, it's a good question. I think it was a pretty novel approach at the time. You know, Eske is very much open. He's an open book, communicator, it was a pretty powerful moment. You know, the thoughts that ran through my head were, this is momentous, because it changes everything about the way science has, and will view Native people on this continent. And in this state.

Alisha Wainwright 22:05

Eske, how do you reconcile a curious brain with the respect of other people's traditions? How do you build that relationship of trust?

Eske Willserslev 22:14

I mean, my meeting with Shane was incredibly important, right? Not only did he teach me, you know, how to look at these things - why are some tribal members resistant? Why is there resistance? These sorts of things. But Shane also brought me to all the communities in Montana. Right? And, and just the simple thing, which seems super naive today when I look back at it. Even though I had read about Native Americans, and different tribes and different bands and all that, I kind of had this kind of naive view that It's like meeting, you know, one country. Or, you know, it’s all the same.

Alisha Wainwright 22:55

Yeah, “kumbayah”, sure.

Eske Willserslev 22:56

Yeah, yeah, exactly, right? I mean not kind of realising, well, I mean, it actually matters whether you are a Crow, or whether you're Northern, Cheyenne, or Salish, or whatever, right. So just that kind of, of experience that well, you're actually dealing with different nations that have different views, different cultures, different beliefs, and so forth, was incredibly enriching. For me, I of course, also learned, as Shane just talked about, the different forces in the community, right? You have people who are conservative or, or kind of resistant towards new things. You have people who are traditionalists, you have people who are progressives, you have all these kinds of - you can say forces working within a community, and, and how do you, how do you approach it? Right? I mean, how do you approach this kind of situation, which is by no means easy, but Shane showed me ways to be completely honest, to be completely frank. Without Shane, for example, with the Anzic Child, I messed up. I mean, that's the bottom line. But now I only half messed up. Right. And I was kind of saved before I screwed it all up. For example, I didn't know any Native Americans in Montana, I had absolutely no contact to any communities, to any peoples, right? The only one I knew was a white farmer, who picked up by accident, this skeleton, basically back in the 60s, right. I mean, I approached something called the burial board at the time, which I was told was the governing body, you know, responsible for these things. And at the time, it was a white archaeologist who was the chairman, who basically didn't believe that native people should have much of a say in these things. So she blocked my way to getting access to any community members, right. So I couldn't really move. I was stuck, right? I couldn't, I didn't know anybody. And the official body, I should go through kind of blocked me. And because of Shane, right, because of my meeting with Shane, he bypassed that block, right? And got me in touch with these communities, right? And I could engage, and I could learn, and try to adapt, etc. So it was a crucial learning that I took with me, of course, for the rest of the trips. And it's hard, I'm just saying, it's actually hard to get it right. It's not that easy. Because when you get it right, there's always somebody who will still be pissed.

Alisha Wainwright 25:50

Well, that is humanity, you know, when you can make everyone happy. And I do feel like what I'm hearing between the both of you is not only a deep sense of friendship, but also two things - communication, and respect.

Eske Willserslev 26:05

And I would add, I mean, I think Shane's engagement has made a huge difference. Compared to the first time we visited, for example, the Blackfeet community, right, and then when we visited, again, later, I mean, this was, I think, an example of, to me, at least of a community, who really started by being very sceptical. But then, because of Shane, and his contacts and engagement, it really changed their mind, right. I mean, the room was full, right? When we came the second time and reported back on the studies, and the results we found and, you know, our future ideas? And, you know, so yes, things are moving slowly, but they are moving, I think. And this is due to people like Shane, for sure.

Alisha Wainwright 27:02

I think it's the both of your work in tandem. And it's also the work that is a stark reminder that, as always, indigenous people have the histories and information that opens up our world, and that the erasure of those traditions, erases so much value. Shane, I'm interested to know how the acknowledgement of this has given indigenous people the agency to maybe even run their own projects, or do their own research in this area. Are you finding that there's more folks interested in archaeology in, you know, genomics and things like that?

Shane Doyle 27:40

Absolutely. It's becoming a growing interest in Native youth. I think now, we're at a point that native communities trust this work more than they ever have in, you know, a long time - ever, maybe. And it's because of the work that Eske has done, and emphasising repatriation with all of the ancient DNA that he studied. You know, all of his success stories here in the West, where a lot of the ancient DNA still resides. You know, tribes feel like they've been respected. And they're equal partners at the table. And I think, you know, this is kind of the last frontier really, for Native people, and for really, for genomes research - Native people in North America and in Montana. And the more we can open up the sequencing of communities here in Montana, I think the closer we'll be to really finding out the truth about Native people across the continent.

Alisha Wainwright 28:40

A question for you both: what excites you most about where this research is heading?

Shane Doyle 28:44

All of it excites me. You know, I mean, I'm interested in everything. I'm interested in the disease - you know what Eske said at the beginning about predicting the future. There are so many different diseases that plague Native communities that genomics could help to solve and explain. Diabetes is an epidemic in the Crow community. Addiction, alcohol addiction. You know, heart disease, cancer. And then there are also some diseases that we don't ever seem to really have very much of, like, for example, dementia. So there are things that we want to uncover about ourselves that seem to be positive. And then I'm also curious, like I said, about the history of Montana, like, how closely are the tribes related? When did they last connect with one another? And how far apart in time was that? So there's a lot of stuff I want to learn.

Eske Willserslev 29:35

You know we are doing work all over the world and have been doing work all over the world on human history. But I would say, nothing like the Americas are closer to my heart. I mean, I've been all over the place, right. And worked with many people - very exciting projects and exciting people, and so forth. But there's just something about the Americas that, I mean, it's for me going to Montana, and to the Northern Plains areas. For me, it's like coming home, I know I'm a white Dane. But it feels for me, it's like the first time I came there, it was just like, I'm home. I’m at a home I’ve never been to before, but it feels like home. So it's very close to my heart.

Alisha Wainwright 30:24

It feels like what brings you most joy is the relationships and connections you're making with these communities.

Eske Willserslev 30:30

For me, of course, the research has been exciting, But I would say just equally exciting, and probably more exciting, really, has been meeting thes living people like Shane, coming from different backgrounds, different ways in these communities of looking at the world, right. And I have as a person changed the way I look at the world, through my meetings with these peoples, right. I remember for example, when we went into, you know, the cave sites where there’d been human remains, they always left a present, right, either tobacco or something else. And they said to me, when you take something, you should always leave something, right? And I was thinking, if we in our part of our world, right, had lived by this very simple rule set, right, we wouldn't be standing facing climate change, and pollution, and I mean, so we have a lot to learn right? in the way we look at the world, and to me it has been a - I have to say - a true gift really, to learn these things and I have incorporated them into my life. I mean today when we take any human sample, whether it's a Danish Viking or whatever, I leave a small piece of tobacco, right, I take snuff, and I open my snuff bag, and people are saying - what the, what are you doing, right? But, you know, it's wonderful to, and it's a privilege to learn about other peoples around the world and how they live, and how they look at things, and we can learn a lot from each other. That's my, basically my learnings.

Alisha Wainwright 32:16

It’s exchange of ideas, you know, science practices, I think that that's incredible. Shane, is there anything you want to add, as we wrap up our conversation?

Shane Doyle 32:27

This has changed my life, you know, in ways that I could have never imagined and I'm just excited about the future. Because I think, you know, as much as we've done already,, there's still much more to come. And I'm looking forward to that. I hope we can, again, continue this conversation in years to come.

Alisha Wainwright 32:44

Yeah, I look forward to seeing you both in ten years to discuss not only the science, but also your friendship. Because I do think, you know, as impactful as the science, it’s the human connection that’s probably the most compelling thing I'm taking away from this conversation. So I appreciate you both. Thank you.

Thanks for listening to this episode of When Science Finds a Way. And thanks to Eske Willerslev and Shane Doyle.

It was amazing to meet these two. Their friendship was so evident in our conversation – it felt like a real-life example of the good things that can happen when science and indigenous culture work together.

For this episode, we’d also like to thank Alex Brown, who advised from the perspective of an Aboriginal Australian.

When Science Finds A Way is brought to you by Wellcome.

If you visit their website - wellcome.org – you’ll find loads more information about ancient DNA research, as well as full transcripts of all our episodes.

If you’ve been enjoying When Science Finds a Way, be sure to rate and review us in your podcast app. And you can also tell us what you think on social media - just tag Wellcome Trust - with two Ls - to join the conversation.

Next time, we’ll be talking about how sleep treatments are being used as a remedy for serious mental health problems.

When Science Finds A Way is a Chalk and Blade production for Wellcome –a global charitable foundation that supports science to solve the urgent health issues facing everyone.

Show notes

When Danish geneticist Professor Eske Willerslev led the team that sequenced the first ancient human genome in 2010, he opened up a world of research possibilities with global significance. But this potential comes with risk. Research into DNA from ancient remains can upend understandings of history and ancestry within living indigenous communities and violate cultural sensitivities.

In this episode, Alisha speaks with Eske alongside Dr Shane Doyle, a member of the Crow Tribe in Montana, USA. Eske and Shane have turned a collaboration into a friendship that demonstrates the power of an exchange between ancient customs and emerging science.

Together they discuss the possibilities and the pitfalls of ancient DNA research, and how to build mutual trust and respect between indigenous communities and scientists.

Meet the guests

Next episode

Alisha speaks to Professor Daniel Freeman about the importance of sleep and its potential in fighting the global mental health crisis.

Transcripts are available for all episodes.

More from When Science Finds a Way

When Science Finds a Way: Our podcast

Our podcast is back with a third season, uncovering more incredible stories of how scientists and communities are tackling the urgent health challenges of our time.