Episode 2: How is research helping the fight for equality?

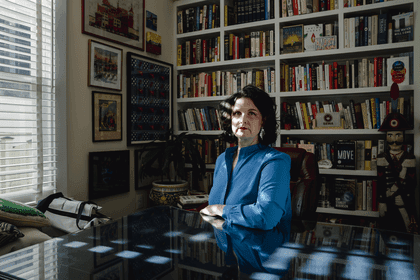

Professor Susan Golombok joins Alisha to discuss how her research into different family structures has changed laws and perceptions on same-sex parenting.

Listen to this episode

Speakers: Jean Downey, Alisha Wainwright, Susan Orr, Susan Golombok

Susan Orr 00:04

We were just the participants. That's all we were, we just took part in a study and we find it so interesting and so engaging and so enriching. You know, research has a place. Just as activism has its place, and they're not completely in different spaces, they connect.

Alisha Wainwright 00:25

Welcome to When Science Finds A Way, a podcast about the science changing the world. I'm Alisha Wainwright, and on this series, I'm meeting with scientists and researchers who are actually making a difference, as well as the people who have inspired and contributed to their work. Forget labs, forget white coats, we have something a little different for you this episode. The guest you are about to hear from is a woman who can make the rare claim that her work has had a tangible impact in the everyday lives of families around the world.

Susan Golombok 01:01

When the research actually does have an impact, there is a new policy or a new piece of law, well, I mean, that's hugely rewarding, and it makes it just feel, of course, we must carry on doing this, it is making a difference to people's lives.

Alisha Wainwright 01:15

Her pioneering body of research into new family forms, conducted over the past 40 years, has helped inform public policies you might have heard of. I'm gonna give you just a few examples. Susan's work was cited in submissions to the US Supreme Court for Obergefell versus Hodges, the case that led to the ruling in favour of marriage equality in 2015. In 2018, she was invited to give evidence to the French Parliament's Committee on Bioethics, which led to a bill allowing French lesbian couples and single women to use assisted reproduction services for the first time. In the UK in 2019, her work helped change the law to allow single parents, often gay men, to become the legal parents of their children born through surrogacy. And just earlier this year, she published the final phase of a twenty-year study into families using assisted reproduction. It made headlines around the world with its conclusion that assisted reproduction kids grow up just fine. Professor Susan Golombok is from the Centre for Family Research at the University of Cambridge, and author of the recently published book, We Are Family. As you'll hear, Susan is empathetic, objective and modest, but behind all that she has a dogged determination and belief that the scientific process can combat injustice. She really broadened my perspective on what it means to do scientific research, and showed me the kind of staying power you need to sustain that research over years and decades. Here's my conversation with Susan.

Susan, welcome to the podcast. It's great to have you with us.

Susan Golombok 03:03

Thank you. It's lovely to be here.

Alisha Wainwright 03:05

We're going to travel back to the 1970s, which is when your research career started, into new family forms. And we need a little history lesson here on the custody cases and what they were like back then. So if parents found themselves in court, custody was pretty much always given to the mothers, right?

Susan Golombok 03:23

That's right. So in those days, in heterosexual families, when the parents separated or divorced, custody was almost always awarded to the mother, because it was thought that it was better for children to be raised by their mothers. So it was only in very extreme cases, that the mother had severe physical illness or mental illness or was in some other way, completely unable to look after her children, that custody was awarded to fathers, except if the mother happened to be lesbian. And in that case, custody was never awarded to the mother and always awarded to the father.

Alisha Wainwright 04:06

Oh, gosh, that just seems so unreasonable, that just because of your sexual orientation, your children are being pried from you. I mean, what was the concern? And what were they making these decisions based off of?

Susan Golombok 04:18

Yes, well, good question. The decisions were really being based on prejudice and assumptions about what would happen to children if they stayed with her lesbian mothers. So what happened in these court cases which were being held in, in the UK, the US and other countries of the world was that an expert or expert witnesses will be brought in on behalf of the mother and the same on behalf of the father. And the experts brought in on the father's side would argue that because they were growing up with a lesbian mother, the children would then show psychological problems, they would be teased and bullied by their peers, they would show atypical gender development, which in these days were seen as a problem, of course, it's all very different today. But back in the 1970s, if a child didn't conform to stereotyped gender roles, they were seen as having a psychological problem. And in their summing up, the judges would generally say, well, in the absence of any scientific evidence on what happened to these children, they would then award custody to the father.

Alisha Wainwright 05:33

And so it's really these sort of assumptions and fears that weren't based on any empirical data at all. And then that's where you come in, right? So you embarked on a study to examine the welfare of children in lesbian mother families. So tell us what you found.

Susan Golombok 05:49

What we did was to look up the questions that had been raised in custody cases about the families and the assumptions that have been made. So one was, firstly, that the children would show emotional problems or behavioural problems, and we found they were no more likely to do so than children raised by heterosexual mothers. It was also argued that the children would be confused about their gender, they wouldn't know if they were boys or girls. And they would show gender or behaviour that wasn't typical of their sex. So what we found in our research was that the children were no different, they were no more likely to have problems, if they grew up with two women in a lesbian relationship compared with a heterosexual mother. That was our very first study. And at that time, two very similar studies were carried out in the United States that came to exactly the same conclusions. And that's important, because, you know, you can't just come to strong conclusions based on one piece of research.

Alisha Wainwright 06:57

Oh, this makes me laugh, because it's like, you're like, “well, you can't just have one study”. I'm like, well, they had none. So frankly, no one is better than none.

Susan Golombok 07:06

Oh, I completely agree with you. Absolutely.

Alisha Wainwright 07:09

So this led to you being called on occasion to court as an expert. And so I'm just curious, what was that like for you? I mean, up until this point in your life, had you even been to court yourself?

Susan Golombok 07:20

No, I'd never been to court in my life. So I actually found it rather interesting. Most of it actually is spent sitting outside the court waiting to be heard, which can go on for a very long time, and often over days. So that was a surprise. But when I actually was called as an expert, it was interesting, because I would be cross examined by the barrister counsel on the father's side, who would try and discredit the research. And that was their job. But I found it partly annoying, but partly interesting to see what their criticisms were, what they chose to focus on. And I quite enjoyed defending it. But also, I could see that some of the criticisms were actually valid, because, you know, no piece of research is perfect. This was the first study of its kind. And, you know, it was legitimate for the opposing barrister to say, this might be a biased group, you know, perhaps because of the prejudice against lesbian mother families, that those mothers whose children were having difficulties wouldn't have volunteered to take part in the research, for example. So that's really what triggered – these criticisms are what triggered the next study, and the study after that.

Alisha Wainwright 08:49

And we will get to those studies in a minute. But before that, we actually tracked down some parents who took part in one of your earliest studies on lesbian mother families. We thought you might like to hear their reflections on taking part. Here's Jean and another Susan.

Susan Orr 09:05

We had this opportunity to be part of the study. And, you know, we leapt at it. I work in a university, you know, I would want to support research where I can and know how important it is to get participants. And so we were, you know, well up for being part of it. And the piece of research that we were lucky enough to be part of was the housework project, where we had to basically write down what we would do, how we managed housework individually. Very old fashioned, paper and pen, filling things in on a sort of housework kind of register, if you like, at regular intervals for several weeks. And as I understand it, her key , finding was that because we were less gendered in the way we allocated housework, we were more efficient as a household and that basically, at that time, straight families were more gender divided in who did what, and we were, as two women, less divided on who did what. And that had an efficiency to it. It really helped, where there were cases where they were threatening to take children away from women in the courts, that actually, she was beginning to establish a research base that showed that, do you know what, the kids are okay. The kids are okay.

Jean Downey 10:20

An amazing piece of research, and I think, you know, that the conclusion from that was that lesbian parents played with their children more, so gave them more opportunity, just to be creative. And that, you know, that that play goes a long way. And I think, actually, you know, what's born out of that research is that you can see, you know, we have got children that have done so incredibly well.

Susan Orr 10:44

You know, obviously, I work in a university. So I would say this, wouldn't I? But research can make a difference. We found it transformative, being part of it. We were just the participants. That's all we were, we just took part in a study, and we found it so interesting, and so engaging, and so enriching. But of course, you know, it does show that, you know, research has a place, just as activism has its place, and they're not completely in different spaces, they connect.

Alisha Wainwright 11:12

Susan, you have fans! What was it like hearing that?

Susan Golombok 11:17

Well, it was, it was lovely to hear that. But to hear them be so positive about the research, it also made me laugh a bit, because it's funny what people remember, because the housework side of the study was one tiny part, but it's obviously the bit that really stuck with them.

Alisha Wainwright 11:34

Because that's what they talked a lot about at home. I'm sure they ran it efficiently, but not without a few certain conversations.

Susan Golombok 11:42

But it was lovely to hear.

Alisha Wainwright 11:54

It really sounds like, once you started getting into it, and you saw the prejudice and the injustice happening, it's really that that pushed you to keep doing it, because you're seeing a real world impact happening.

Susan Golombok 12:09

Well, that's right. I think, you know, as students, as I was then, you know, we're often very idealistic, we wanted to change the world, as young students do today. You know, it was, it was a kind of passion that just felt wrong to me. As the criticisms came in about the research, it kind of prompted the next study and the next study, because, you know, some of them were legitimate criticisms. So it was important to then find out what happened when the children grew up. So that's why we went back and we saw them all again, when they were in their mid 20s. And then, another criticism was that when lesbian couples started having children through donor insemination, which meant that the child was raised by lesbian mothers, right from birth, then we were told, those of us who were doing this research, “well, you can't assume that your findings from studies of children who spent their early years with the mother and father will also apply to children born to lesbian mothers from birth” – because children's early years do make a difference in many ways to their development and wellbeing, and we know that. And people who were critical of the research would say, “well, actually, you know, having a father in the first few years may have been what helped these children, children who don't have a father around, they may have problems you can't just assume they won’t”. So when lesbian women started, in the 80s, but mainly the 90s, to have children through donor insemination, it prompted another group of studies.

Alisha Wainwright 13:57

So it's kind of incredible – in the 70s, you have this almost Pandora's box, of just one new emerging family. And then you go from that, to lesbian mothers who have sperm donors. And then you go to even newer families, like surrogacy or families that are started with invitro fertilisation. I mean, there's pretty much no new family up until this point that you haven't studied. You have gay fathers, single parents by choice, adoptive parents – your body of work is so broad, we cannot even begin to skim the surface of what you've looked at. But whatever this study, your work has been right at the heart of challenging preconceived notions of what family means. So I wanted to ask how important is scientific research in countering prejudice and assumption in society?

Susan Golombok 14:48

I think scientific research is really important, because with any controversial issue, you get a whole range of opinions and many of these opinions are driven by people’s political beliefs or religious beliefs or moral beliefs, and so on. And into that mix, I think it's really important to have scientific data on what actually happens.So in this case, we're talking about what actually happens to parents and children. I'm not saying that that should determine everything, of course, laws and policy has to be made based on other considerations.

Alisha Wainwright 15:29

But you need some empirical data.

Susan Golombok 15:31

Yes, I think where the empirical data is really important is to counter false statements that people make, especially around the time of thinking about new policies, new legislation, to try and promote their particular view, their particular cause. And, you know, this can be very distorted, it can be done right or wrong. And unless you have good scientific studies, then nobody can pick it up and say, “well, actually, you're wrong about this. It's not true that these children experienced problems, or these are bad parents.”

Alisha Wainwright 16:11

For this kind of work, you speak to the same families over years and years, and seeing children through their childhood. What was that like? And did you find yourself getting attached?

Susan Golombok 16:22

Yes, well, I mean, at the very beginning, when I did all of this work myself, I would see five year olds, but I then went back to see when they were twenty-five. And that was amazing. I remember one young boy, who, when I visited him when he was five, was actually a real terror. He had, you know, he just wouldn't stop moving. And he was driving his mothers a bit crazy. And he's stood out in my mind, because I remember thinking, if I had a child like that, I don't know how I could cope, because he was just really, really active. And then I re-met him as a twenty-four year-old art student, when he was able to reflect on his growing up and what it had been like for him, most interestingly, how things are changed. Because he talked about, as a teenager, he had been teased and bullied at school, he'd had cigarettes stubbed out on his skin, he'd had his head flushed down the toilet, and all of these things, because he lived in a lesbian mother family. But by the time he was, you know, twenty odd years old, it was all seen as really cool. And his friends were saying, you know, it's really amazing. It's so cool. We've got lesbian mothers. And it was really interesting to hear from a child who had gone through that, actually, rather quick change in social attitudes.

Alisha Wainwright 17:53

Well, not only is the research changing people's lives, but changemakers are also listening. Your studies have actually had real world impact. We're talking about influencing policy change, governments around the world citing your work, for example, the US Supreme Court and same sex marriage legislation. So, let's be honest, this is not something that every scientist has the privilege of seeing in their lifetime. So what is it like, to not only meet people who, in personal ways, their lives have been changed, but also see actual legislation change over the years because of the research and activism and several other things? But I mean, the research played a very large part.

Susan Golombok 18:33

Yeah. So the first thing to say is, this wasn't all my research, there is a community of researchers out there. So that's nice, to have other people who are doing similar things, understand what you're doing, come across the same problems and issues, so that it's like a sounding board, other people you can speak to. I mean, some of my closest colleagues in this field are in the United States, where sometimes the circumstances or the legislation is different, but the issues are often the same. And that's always really interesting and helpful.

Alisha Wainwright 19:08

You call it interesting and helpful, but it's a bit more than that for parents when big policy changes like same sex marriage come along. I want to bring back Jean and Susan, your participants from earlier. They have two daughters, Bea and Alana. When they were born back in the 1990s, there was no legal framework to bind their family together in the UK. That eventually changed sometime later in 2014, with the introduction of civil partnerships for same sex couples. Jean and Susan reflect on family life before and after. Jean started by telling us how the family got around the lack of legal recognition for their daughters.

Jean Downey 19:52

There was no framework for our family relationship. For me to take Bea to the doctors as her mother, I wouldn't have been seen as her mother, and it would be the same in an education setting as well, what we did to kind of challenge this, we found a legal loophole. So we were in, I think it was about 1995, we were the first lesbian couple, to go through the family courts, to do joint custody for each of our children. So in effect, Susan had to pass over rights of Bea to me, and I had to pass over rights of Alana to Susan.

Susan Orr 20:37

But what we hadn't realised when we did this was that it was just for the duration of the children's childhood. And that became, you know, that didn't exist after they were 18. Now, many of you would sort of think, well, why does that matter? It's been a source of great sort of fury, and anger to me personally, because what it means is my eldest daughter is not recognised. And of course, you may hear my accent, you know, I'm Irish. And of course, I've got one daughter who can get an Irish passport and one daughter who can't.

Jean Downey 21:12

Civil partnership and gay marriage now does give you rights to your children. So you know, whether you're a lesbian couple, and you've got biologically a child each, or you're, you know, a gay man, and you've got children, it gives you those rights. So it was really important for us, then, actually, that it did start to kind of, I guess, give our family that legitimacy that it didn't have before as well. It's not the reason we did it, actually, we just did it to have a good party. And just to celebrate our relationship.

Susan Orr 21:47

I call it the drop-down menu place in life. So that when there's a drop-down menu, you know, we can, whether it's something as boring as your pensions, whether you're booking a holiday, you're in the drop-down. Before civil partnership, you know, what did we do? We'd been together for twenty years, did we say we were both single? It's just patently ridiculous. So yeah, it had symbolic power.

Jean Downey 22:10

These days, I think, because of civil partnership, and gay marriage being an accepted part of the UK now, I would never feel as difficult as as before those things were in place. So you know, our family is much more established now, I would say, even though our two daughters are well grown up and well on with their own lives. I feel like we're a much more established family than we were back in the 90s. It shows that attitudes have moved on, and you know, from that, there's real hope. So I wonder what 2052 will look like in terms of those attitudes, then.

Alisha Wainwright 22:59

The privilege of being in the drop-down menu. I thought that that was so perfectly explained to me. You take such basic things for granted, especially in creating a new family when you come from a more traditional lineup, but even just having your family in a drop-down menu, it was a huge deal to them. I just can hear it in their voices.

Susan Golombok 23:21

Absolutely. And that was actually quite surprising to me as well, because I hadn't heard it put that way before. And it just really illuminates the issue, I think, so well.

Alisha Wainwright 23:32

Okay, so I'm gonna ask you a huge and probably a totally unfair question, but I am going to put you to task. I would like you to sum up the findings of your life's work in one sentence.

Susan Golombok 23:48

I would say that studying different family constellations has allowed us to come to more general conclusions about what really matters for children. And that is that family relationships, the quality of family relationships, matter much more for children than structural aspects of the family, such as the number, gender, gender identity, sexual orientation, or biological relatedness of parents.

Alisha Wainwright 24:25

As long as they're loved is kind of what it sounds like.

Susan Golombok 24:27

Absolutely, yes. And I also think it's important to remember that not one of these families happened by accident. They were either formed because parents went through years of infertility and fertility treatment to have their children, or they had to surmount huge social hurdles, or both sometimes, and these are all really wanted children. So it's not surprising that they have very close loving relationships with their parents.

Alisha Wainwright 25:04

I love to hear that. I'm also curious what you think makes you so well suited to pioneering this area of research?

Susan Golombok 25:13

I think partly at a kind of micro level, I find families endlessly fascinating. I'm always interested in hearing people's family stories, or experiences with their children, or their grandparents, or where they've come from, and their day-to-day lives. So I think I'm just nosy – perhaps I was curious? Nosy is just another way of putting it, but I do find hearing about people's lives and their family lives just something that always interests me. At a broader level, I suppose, I'm interested in the issues I've always been interested in, in women's issues, in the women's movement. I've been, always an ally, I hope – I hope I’m seen that way – to the LGBTQ+ community. And so, I think it's partly because I don't like the injustices that I have seen over the several decades that I've been doing this work. So that's something that drives me on. And then when the research actually does have an impact, when I know there is a new policy or a new piece of law that has, to some extent, been informed by our research, well, I mean, that's hugely rewarding. And it makes it just feel, of course, we must carry on doing this, because actually, it is making a difference to people's lives. So it's not difficult from that point of view.

Alisha Wainwright 26:53

Just out of curiosity, when you were growing up, did you find yourself also being curious about your peers at school and kind of how they were raised? Or maybe how you were raised, and how it was different from your peers?

Susan Golombok 27:06

I suppose. Yes, I suppose I've always been interested in people's families. You know, I would always as a kid, like reading books to do with siblings, or friendships and families and so on.

Alisha Wainwright 27:19

Are you an only child?

Susan Golombok 27:20

Yes. Can you tell?

Alisha Wainwright 27:22

I'm an only child!

Susan Golombok 27:24

Maybe that’s why I've been interested. Because, you know, I grew up with no siblings. So I suppose I spent more time than other children in other people's families, because I would visit my friends more, our neighbours more, and I would see what life was like, with larger families, more siblings around. I mean, I actually have never minded being an only child, I think it has lots of advantages. I do feel I grew up in a very loving family. And I couldn't have had a happier childhood. So certainly, my interest in all of this doesn't come from my own experience of difficulties in my family. I think maybe I'm just kind of nosy about other people.

Alisha Wainwright 28:15

Hey, that's okay. So, in 2023, we have so many new family forms compared to the 1970s. But which new families are you most blown away by? Or are you most curious about?

Susan Golombok 28:31

Some of the recent work we've done, we are studying children with transgender parents. Recently, we have carried out a study speaking to 35 children who have experienced their parents gender transition, asking them, you know, how that felt for them, , and what difference it made to their lives. Interestingly, the findings were very similar to our earlier studies of children with lesbian mothers and gay fathers: that, within their family, relationships were generally very positive, although there were some difficulties between the parents sometimes, because going through a gender transition does have challenges associated with it. But for the children, as long as their parents spoke to them, were open with them about what was happening, then, that made everything much easier. And so generally, their family relationships were just as strong as in any other family, but the problems they experienced was when they were outside with their families, when they'd be in the street and people would make unpleasant remarks, upsetting remarks, and that was a problem. So, just like in the earlier days of children with lesbian mothers or gay fathers, it was the reaction of outside society that was problematic, not their own family. So that's one thing. We are also studying children born through egg donation, where the egg donors are no longer anonymous, because in the United Kingdom, the law was changed to remove anonymity of sperm and egg donors. This year, 2023, the first children born after the law changed in 2005, will become adults, they will become 18 and be legally entitled to ask for the identity of their donor. So that will be very interesting to see how that plays out, how many young people will come forward and ask us for this information, and how that will all go. We've been studying children born to single fathers by choice as well as single mothers by choice, children in co-parenting relationships, all kinds.

Alisha Wainwright 31:07

With all these new emerging families, it really does sound like you'll never be out of the job.

Susan Golombok 31:12

It does sound like that. When I first started, you know, it started as a student project with ten families. And then, all kinds of families popped up that we had never even imagined at the time. You know, we hadn't thought about the idea of test tube IVF babies. Nobody knew about that at that point. And then two years later, in 1978, the first test tube baby was born. And ever since then, more and more different family types have appeared on the scene. So I think, you know, the changes to families are going to keep researchers busy for very many years to come.

Alisha Wainwright 31:56

Susan, thank you so much for taking the time to talk to me today. You're such a pleasure, and I look forward to seeing what new research comes down the pipeline.

Susan Golombok 32:06

Thank you, Alicia.

Alisha Wainwright 32:12

Thanks for listening to this episode of When Science Finds A Way. And thanks to Susan Golombok, and our contributors Susan Orr and Jean Downey. Look at how far we've come since Susan started her research in the 70s. And her studies were an important part of all of those changes. And it's also touching to hear directly from one of the families whose lives have been affected by the work Susan has done for decades. When Science Finds A Way is brought to you by Welcome. If you visit their website wellcome.org. – with two l's – you'll find a whole host of information about research into family forms, as well as full transcripts of all of our episodes. Make sure you follow us in your podcast app to get new episodes as soon as they come out. And if you feel like you've learned something important or interesting, or you just want to support the podcast, spread the word and share it with people you know. Next time we'll be hearing about how climate change is affecting our health, and how women are leading the charge and making us more heat resilient. When Science Finds A Way is a Chalk and Blade production for Wellcome, a global charitable foundation that supports science to solve the urgent health issues facing everyone.

Show notes

In the 1970s, when a heterosexual couple divorced, courts almost always awarded child custody to the mother, except in one scenario: when the mother had come out as a lesbian.

Professor Susan Golombok was determined to challenge prejudices and shine a light on the realities of same-sex parenting. She began studying a range of different family structures to build up a body of evidence which, over the course of her life, has had a tangible impact on everyday families around the world.

In this episode, Alisha is in conversation with Susan about the influence and breadth of her work, from broadening societal perceptions to changing laws. We also hear from a couple who took part in the research and learn why it was so important to them, and the legacy it has left for families everywhere.

Meet the guest

Next episode

As the world gets hotter and hotter, so do we – and just like crops and wildlife, we’re struggling to cope with what extreme heat does to our bodies. Kathy Baughman McLeod joins Alisha to talk through the realities of what heat stress does to us, how workers across the globe are feeling the heat, and the tangible solutions being implemented to increase resilience.

Transcripts are available for all episodes.

More from When Science Finds a Way

When Science Finds a Way: Our podcast

Our podcast is back with a third season, uncovering more incredible stories of how scientists and communities are tackling the urgent health challenges of our time.